[This article is also a weekly newsletter. Sign up for Race/Related here.]

The enslaved children were sold and shipped from Virginia to Louisiana with their families in the 1830s, far from the world they knew and the people they loved.

Her name was Eliza Randolph. His was Miles Green. They sailed at different times and on different ships, but both ended up on a plantation near the banks of the Mississippi River, not far from Donaldsonville, which sits about 41 miles south of Baton Rouge. In their sorrow, they ultimately found comfort in each other.

By 1840, more than two million Black people were enslaved in the United States. They experienced heartbreak and brutal treatment at the hands of enslavers who tore families apart for profit. Yet amid the trauma and hardship, love still blossomed, a balm for a people determined to resist and survive.

This Black History Month, I want to celebrate the love stories tucked away in the archives of the 19th century and the couples like Eliza and Miles who held on, against the odds. I write about slavery and its legacies, and these stories glimmer like gems in rocky soil, highlighting the humanity that endures even during the darkest of times.

“It’s important because we need to understand the value that African Americans placed on family relationships in general and on marriage in particular and the sacrifices they made, often at great costs,” said Tera W. Hunter, a historian at Princeton University and the author of “Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century.”

Proponents of slavery often justified the practice of breaking up Black families by arguing that Black people were incapable of “forming meaningful relationships in the ways that white Americans did,” Dr. Hunter said. That argument, she pointed out, is belied by the archival record.

“When you read letters and narratives of former slaves speaking in their own voices about what these relationships meant to them, and what they were willing to do to protect those relationships and to sustain those relationships, that’s very powerful,” she said.

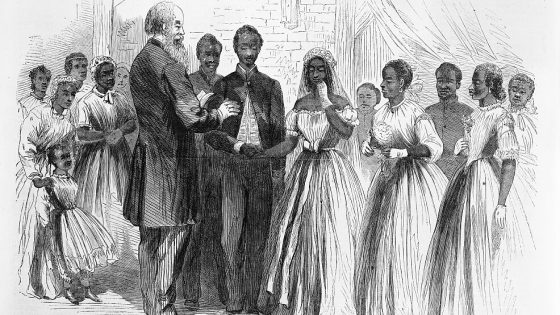

Eliza and Miles married in the parlor of their enslaver’s home in the 1850s, archival records show. She was working as a house servant then, tending to the white family who held them captive. He was laboring in the fields of the sugar plantation called Chatham.

Miles was one of the 272 men, women and children sold by Catholic priests in 1838 to save the college that is now known as Georgetown University. Judy Riffel and Malissa Ruffner, the genealogists who have been researching the 272 for the Georgetown Memory Project, an independent nonprofit, discovered the pension file and passed it on to me.

“They were both young folks then and that was the first time either of them had been married,” said Catherine Randolph, Eliza’s sister-in-law, whose words were recorded in an affidavit taken decades after the ceremony.

Sold as children, the bride and groom knew the perils that enslaved couples faced. But for a few years, they built a life together. They had a home in the slave quarters and soon had a baby girl, naming her Emily.

It was their enslaver’s son who shattered their lives, the pension records show. He wanted Eliza for himself and tried to break up her marriage. He forced Eliza to leave her home and moved her to his plantation several miles away, where, the records suggest, he repeatedly raped her. She would have several of his children.

“My master did not allow Miles to come to see me,” Eliza recounted years later.

Miles disobeyed that order. When darkness fell and his enslavers retired to their beds, Miles slipped out of his quarters. Enslaved people who left their plantations without permission were often jailed, whipped or sold. He knew the risks. But he was determined to see his wife.

“He would steal away and come to see me two or three times a week,” Eliza said. “We kept that up till the war came on.”

In 1862, the Union Army seized control of New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy. Chatham and a number of the plantations along the Mississippi River soon fell under federal control.

Several Black men on the plantation decided then that they would no longer tolerate life in bondage. In the spring of 1863, the enslaved men began to run, abandoning the estate, finding their way to military camps and enlisting in the Union Army.

Miles considered his own circumstances, and decided he would run, too. By then, he and his wife had several children.

“He came to see me first,” Eliza remembered, “and to tell me goodbye.”

Miles spent three years in the Union Army, military records show, and was promoted from corporal to sergeant. He also contracted smallpox. When freedom finally came, he was sickly. He made his way from New Orleans back to the old plantation, searching for Eliza.

Across the South, newly freed people searched for their loved ones. The lucky ones celebrated in joyous reunions. Some couples, finally afforded the legal protections of marriage available to white Americans, moved to solemnize wedding vows made during slavery and to legalize longstanding relationships. Others posted newspaper ads and relied on relatives and friends, but never reunited with their beloveds.

Miles and Eliza found their way back to each other.

“Just as soon as his time was out he came home and found me,” she said, “and we went to living together right away.”

I recently shared the details of their story with Gerald Brown, a descendant of one of Eliza’s brothers, who has been researching the family for years. “Through all the adversity, they still get together and live out their lives together,” he said.

Life wasn’t easy after the war. Miles remained feeble after recovering from smallpox and was barely able to work. The couple lived apart at times, perhaps because Eliza had to live near the white families she worked for or perhaps because they needed time apart. We will never know their full story, but people who knew them said they remained united, despite their difficulties.

Sometime around 1881, Miles died on the plantation where he first met his sweetheart. Eliza was there, right by his side.

Credit for the National Archives documents: Eliza Green, Widow’s Pension Application No. 637,236, Certificate No. 468,798; Service of Miles Green (Co F, 80th & 88th U.S.C.I., Civil War); Case Files of Approved Pension Applications, 1861-1934; Civil War and Later Pension Files; Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15

Invite your friends.

Invite someone to subscribe to the Race/Related newsletter. Or email your thoughts and suggestions to [email protected].

Source Agencies