Shortly after Jonathan Kanter took over the Justice Department’s antitrust division in November 2021, the agency secured an additional $50 million to investigate monopolies, bust criminal cartels and block mergers.

To celebrate, Mr. Kanter bought a prop of a giant check, placed it outside his office and wrote on the check’s memo line: “Break ’Em Up.”

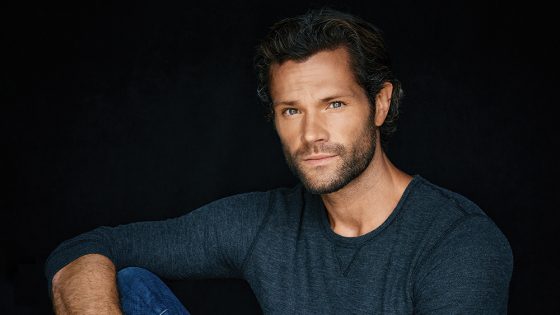

Mr. Kanter, 50, has pushed that philosophy ever since, becoming a lead architect of the most significant effort in decades to fight the concentration of power in corporate America. On Thursday, he took his biggest swing when the Justice Department filed an antitrust lawsuit against Apple. In the 88-page lawsuit, the government argued that Apple had violated antitrust laws with practices intended to keep customers reliant on its iPhones and less likely to switch to competing devices.

That lawsuit joins two Justice Department antitrust cases against Google that argue the company illegally shored up monopolies. Mr. Kanter’s staff has also challenged numerous corporate mergers, including suing to stop JetBlue Airways from buying Spirit Airlines.

“We want to help real people by making sure that our antitrust laws work for workers, work for consumers, work for entrepreneurs and work to protect our democratic values,” Mr. Kanter said in a January interview. He declined to comment on the Google cases and other active litigation.

At a news conference about the Apple lawsuit on Thursday, Mr. Kanter compared the action to past Justice Department challenges to Standard Oil, AT&T and Microsoft. The suit is aimed at protecting “the market for the innovations that we can’t yet perceive,” he said.

Mr. Kanter and Lina Khan, the chair of the Federal Trade Commission, have now taken action against four of the six biggest public tech companies, in a sweeping drive to rein in the power of the industry. The F.T.C. has separately filed antitrust suits against Meta, the owner of Facebook and Instagram, and Amazon.

But Mr. Kanter and Ms. Khan are on the clock to see how far they can take their efforts. The November election could remove President Biden from the White House and take Mr. Kanter and Ms. Khan with him.

More than two dozen people who know Mr. Kanter, including current and former Justice Department employees, described his two-decade rise. Some spoke anonymously to describe confidential government deliberations and presentations.

Mr. Kanter was raised in the Queens, N.Y., apartment where his parents still live. After graduating from Forest Hills High School, he attended the State University of New York at Albany and then law school at Washington University in St. Louis.

“I grew up in a neighborhood with schoolteachers and police officers and taxicab drivers and shopkeepers and people who worked really hard,” he said, and did so with a “belief that the American dream really provided openings and opportunities to realize a better life for future generations.”

He said he connected antitrust enforcement to those values because “it’s about making sure that those opportunities are available to all and making sure that people can succeed on their own merits.”

After getting his law degree, Mr. Kanter worked at the F.T.C. before joining big law firms like Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft and Paul Weiss. At one point, he represented Microsoft. When the company mounted an offensive against Google, which had eaten its lunch in online search, Mr. Kanter made the pitch around Washington that Google deserved additional scrutiny.

He later made similar arguments for other Google critics, like News Corp and Yelp, and said regulators should investigate additional tech giants, too. Simultaneously, he defended corporate mergers in separate industries.

Mr. Kanter’s work against some of the tech behemoths won him fans among those who believed that antitrust laws were an essential tool to make the economy more fair.

“Here was an insider who had also come to very similar conclusions,” Ms. Khan said in an interview in November.

After his nomination by Mr. Biden was confirmed, Mr. Kanter, who often favors formal peak lapels and once wore to a photo shoot an A. Lange & Söhne dress watch that retails for $34,500, debuted his plan for the antitrust division to its staff, people with knowledge of the presentation said.

Mr. Kanter branded his initiatives with catchy code names. A plan for the agency to quickly weigh in on active legal cases got the Gen Z moniker “Real Time AF,” short for real-time antitrust filings. He called a plan to investigate senior corporate executives the “Billionaire Accountability Project.”

Mr. Kanter told his team that, at any given moment, he wanted the department to be able to manage 30 civil lawsuits and another 30 criminal cases. He called the plan “30 for 30.”

The agency was already stretched thin, and some on the staff felt Mr. Kanter was setting unreasonable goals, people with knowledge of the matter said.

His time in private practice also cast a shadow. Mr. Kanter initially didn’t work on lawsuits against Google because he had spent years representing its rivals. When he can’t work on cases, including the challenge to JetBlue’s purchase of Spirit, they are led by his principal deputy, Doha Mekki.

Still, Mr. Kanter has been proactive on the suits against the tech giants.

As a Google antitrust case over online search headed to trial last year, he told government lawyers to be more explicit and prominent with their argument that sheer scale of the company’s operation entrenched its power and made it harder for its rivals to compete, two people with knowledge of the matter said. That idea was a central theme when the case was tried in a Washington courtroom last fall. (A ruling is expected later this year.)

Mr. Kanter also oversaw the final months of the Justice Department’s investigation into Google’s control of online advertising technology. He argued to colleagues that the government should push for the lawsuit to be decided by a jury instead of a judge, which has been the norm in similar civil cases, a person familiar with the matter said. A jury trial is scheduled to start in September.

Mr. Kanter’s work has been scrutinized by critics who wonder if he and his compatriots are pushing the boundaries of antitrust law too far, hurting the economy.

William Kovacic, a law professor at George Washington University and former chair of the F.T.C., said Mr. Kanter had yet to secure a victory in the kind of sweeping monopoly lawsuit that the agency was pursuing against Apple and Google.

“In some ways, he’s still looking for that more prominent trophy to go on the mantelpiece,” he said. “You win one of these monopolization cases, you can take the rest of the decade off.”

In the January interview, Mr. Kanter defended his push to shift how the agency did business. He said the world had changed radically in the last 30 years. People communicate using new mediums, get their information from different sources and conduct commerce on ascendant platforms.

“It’s important that if we’re going to have antitrust enforcement that is fit-for-purpose in a modern economy we recognize those changes,” he said. “And then we adapt to make sure that we are enforcing the letter of the antitrust law and the applicable precedents. But we’re enforcing the law in a way that reflects the realities of today’s economy.”

Tripp Mickle contributed reporting from San Francisco. Jack Begg contributed research.

Source Agencies