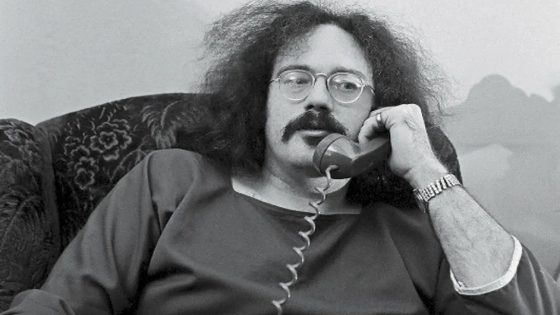

John Sinclair, the counterculture activist and former MC5 manager who helped define that proto-punk ensemble’s radical politics, died on Tuesday at 82.

Sinclair’s death from congestive heart failure at the Detroit Receiving Hospital was first reported by the Detroit News and confirmed by a representative for his family.

Long before social media’s instant impact, Sinclair helped spawn the pointedly politicized alternative newspaper movement as a fast fount of information about the “underground,” as the counterculture was termed at the time, with Detroit publications such as Fifth Estate (which still exists), the Ann Arbor Sun, the Detroit Artists Workshop Press and its offshoot Work Magazine. Later in life, he worked as a spoken-word performer and recording artist with an eye toward what he called “jazz poetry,” recording more than 30 albums with different band names, including the Blues Scholars which included his longtime friend Wayne Kramer, the MC5 guitarist and cofounder who passed away in February this year.

“Sinclair is one of those ‘a lot of things to a lot of people’ kind of guys,” Kramer told Billboard in 2018. “He has a lot of passions, a lot of interests, a lot of causes that he maintains … Not always a saint or the easiest guy to get along with, and sometimes we hated him. But I would say he was a mentor and a friend.”

It was through the MC5 that Sinclair found his greatest fame.

In 1966, the Motor City rock band got a regular gig at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom where they met Sinclair – a radical political writer and White Panther Party leader nicknamed the “King of the Hippies” – and by the next year made him the group’s manager. In turn, Sinclair made them into the official house band of the White Panthers and fueled their radical politics. After bringing the MC5 to the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago (where they became the only band to perform there before police broke up the massive anti-Vietnam war rally) Sinclair got the band signed to Elektra for its 1969’s live album debut, “Kick Out the Jams.”

“He was as a very important part in what the MC5 became,” Kramer said.

John Sinclair was born in Flint, Michigan on October 2, 1941. After enrolling at Albion College in 1960, he dropped out during freshman year. When he attended the Flint College of the University of Michigan, he became part of the university’s school newspaper, The Word, with his interest in writing and publishing acting as clear goals for his future.

After his college graduation in 1964, Sinclair began work as a writer for the jazz magazine DownBeat, and in 1965, delved into poetry, winning high marks with his reading at the now-legendary Berkeley Poetry Conference. By 1967, he and his wife, Leni Sinclair, founded the underground newspaper, the Ann Arbor Sun. Along with becoming a White Panther Party leader around this same time, Sinclair’s building advocacy of marijuana began to get him in trouble.

With two prior convictions for marijuana possession to his name, Sinclair was arrested in 1969 for possession of two joints (he tried to sell them to an undercover police officer) and sentenced to 10 years in prison. The severity of the sentence led many in the music world to rally on his behalf.

At the Woodstock festival that summer, Yippie honcho Abbie Hoffman was thrown off the stage by Pete Townshend for attempting to give a speech about Sinclair during the Who’s set (the group had no problem with Sinclair, and in fact singer Roger Daltrey later often wore a “Free John Sinclair t-shirt; the issue was over interrupting their set). And not only did John Lennon record his song, “John Sinclair” for his and Yoko Ono’s 1972 album, “Some Time in New York City,” the couple, along with Detroit natives Bob Seger and Stevie Wonder, attended a 1971 freedom rally in Ann Arbor in solidarity with Sinclair.

Sinclair was released from prison two days after the rally.

“John was on the forefront of the marijuana movement,” Matt Lee told The Detroit News. “But I don’t think people realized how knowledgeable he was in American music and he was a certified expert in all forms of American jazz and rhythm and blues.”

Along with releasing albums, reading poetry and writing essays on cannabis, he created the John Sinclair Foundation in 2004, an Amsterdam-based, non-profit organization to ensure the preservation and presentation of all of his work in the arts, letters, and cannabis legalization efforts.

Source Agencies