When the Writers Guild of America went on strike last May, union leaders argued that artificial intelligence posed an existential threat to writers, painting a picture of a dystopian future in which TV shows might be crafted by one writer and a machine.

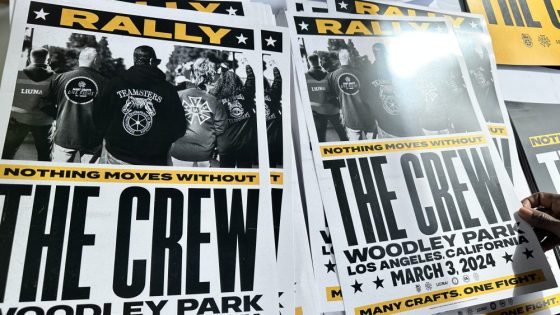

Ten months later, the tone in Hollywood labor circles has shifted significantly. At a March 3 rally in Los Angeles, Matthew Loeb, international president of IATSE, argued that AI has the potential to make union members’ jobs easier.

“We want some of the spoils of artificial intelligence,” Loeb said.

AI is high on the agenda as IATSE looks to set a new three-year contract with Hollywood’s major studios and streamers before the July 31 expiration of its current deal. Like the other unions that have struck new contracts over the past year — the WGA, SAG-AFTRA, the Directors Guild of America and the American Federation of Musicians — IATSE is seeking “guardrails” on AI use. The technology, of course, became a flashpoint in the strikes waged by WGA and SAG-AFTRA.

IATSE negotiations are always a complex matter because the union bargains on behalf of a broad range of disciplines — boom operators, grips, sound mixers, camera operators, costume designers, makeup artists, set decorators and so on. Some may not have much to fear from AI. But others are more vulnerable.

“We are focusing on AI as a tool,” says Jillian Arnold, who chairs IATSE’s subcommittee on AI for the negotiations. “It can incite some fears. We look at it more as a challenge and as a tool within our workplace.”

IATSE Local 700, the Motion Picture Editors Guild, could be one of the first locals to be impacted by AI. The guild’s Emerging Technology Committee has concluded that some jobs could well become obsolete.

“The impacts will be uneven,” says Harry B. Miller III, who co-chairs the committee. “Some things will be great. Some things will be negative.”

Even A-list editors have deep concerns about what AI might mean for the future of their profession.

“Pretty much everybody that I know — from editors to assistants, older people, younger people — are worried about what’s around the corner,” says an Oscar-winning film editor from Local 700.

In February, AI software leader OpenAI released a preview of Sora, a program that can create short videos based on simple text prompts. Asher Pink, co-chair of the Emerging Technology Committee, says he had to “talk people off the ledge” about it.

“We don’t see this sort of technology, in its current state or in the future, being used to edit broadcast-able stories,” he says, adding there are important tasks the models cannot do. “All of these products are being marketed as wonder products that do everything, but it’s not the case.”

Pink and Miller emphasize that models they’ve seen also cannot handle continuity between shots, scenes and sequences or match cuts — simple tasks for human editors.

Technological changes could also fall harder on assistant editors than on editors. Depending on how it is deployed, AI could eliminate some of those assistant roles or change them significantly.

The Editors Guild also represents story analysts, whose job involves summarizing scripts and giving recommendations about whether to pursue them. In theory, that sounds like an assignment AI could handle. But in practice, Pink says, it’s not so easy.

“It can do plot summary,” he says. “It’s not telling you what the story is about. It’s telling you what the plot is about. It’s the story that connects with the audience.”

Pink says there’s a chance AI tools may create more jobs for assistant editors, not fewer. But it’s too soon to tell, which makes for difficult negotiations.

“AI will eliminate jobs, and it will create jobs,” says a prominent member of Local 700. “I’m not happy about this, and yet I am comfortable with its inevitability.”

Carolyn Giardina contributed to this report.

Source Agencies