The potatoes on Andrew Branton’s farm tell you all you need to know about the weather in 2023: rotten.

From late September to January, a year’s worth of rain fell on his Lincolnshire farm. Many of his fields were submerged for weeks, leaving his potato crop unharvestable – the tubers now decomposing in the sodden ground.

The water is now receding, but for weeks the sheer weight of water on many of his fields – around 2,400 tonnes per acre – has left the soil too wet and compacted for sowing spring crops.

“Even if it was physically possible, it’s not economically viable,” says Mr Branton.

He’s far from alone. According to the most comprehensive analysis of Europe’s climate in 2023, it was the fourth wettest year on record across the continent, with December the wettest month ever in places such as the UK.

Extreme weather caused losses of at least €13bn (£11.2bn) and affected 1.6 million people, the report found.

“2023 was really an exceptional year,” says Dr Samantha Burgess, deputy director of the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, which has produced the report in conjunction with the World Meteorological Organisation.

“Europe is the fastest warming continent, with temperatures rising at about twice the average rate [and] with the three warmest years on record all occurring since 2020,” says Dr Burgess.

A series of storms throughout the year caused flooding across central and southern Europe with Slovenia suffering what’s thought to be the costliest disaster in its history. Flooding impacted 1.5 million people.

More from Sky News:

What is cloud seeding and did it cause Dubai floods?

Plastic crisis ‘out of control’

The uncomfortable truth about climate targets

Average ocean temperatures in the North Atlantic, a major driver of Europe’s weather systems, were the highest on record and were a degree or more higher than average for most of 2023.

Europe’s glaciers also suffered historic levels of melting and over 2022 and 2023 combined, they lost 10% of their remaining ice.

In late July, the largest area of Europe ever recorded was suffering from “heat stress” where the “feels like” temperature experienced by people is at or above 46 degrees, according to the report.

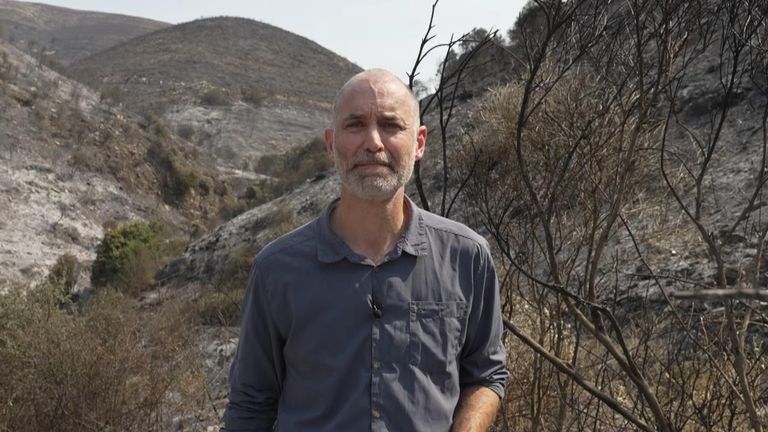

The by-product of that extreme heat was, of course, wildfires – including the largest ever wildfire on record in the continent in Greece.

It’s an irony of the warming climate in a continent like Europe, surrounded by oceans, that climate warming can bring both extreme heat waves and extreme rainfall.

“We know in a warmer climate we will get more heatwaves and those heatwaves will be more intense,” Dr Burges says. “We also know in a warmer climate the atmosphere can hold more moisture, which will mean storm events will be more intense.”

Farmers like Andrew Branton don’t need a climate scientist to convince them of that.

I last visited his farm in the summer of 2022 – the joint warmest year in Europe with 2023 – when his potatoes were baking in nearly 40-degree heat.

Farmers can continue to produce food under such extremes, he tells me. The vagaries of the weather mean not all parts of the country are impacted equally, every year.

But the economics of food production, with low prices a disincentive for farmers to produce surplus, mean climate shocks can be financially ruinous – as well as impacting prices for consumers.

Click to subscribe to ClimateCast wherever you get your podcasts

“Historically, [food] has been worth so little you’re losing money on producing surplus. Realistically to cater for a natural disaster, you need some contingency,” says Mr Branton.

For now, where his fields are dry enough, he’s drilling the compacted soil for this year’s crop and hoping the climate in 2024 is kinder.

Source Agencies