It’s a public holiday in Melbourne and the city’s most famous bluestone laneway, Hosier Lane, is throbbing with people eager to admire the ever-evolving street art that adorns the buildings.

There are footy fans in striped scarves, ex-servicemen and women wearing their medals, tourists taking selfies, young parents pushing prams and diners pouring out of MoVida after filling their bellies with tapas and wine.

But only a few steps from the commotion that has come to define Melbourne’s laneway culture is a group of people, wrapped in hoodie jumpers and sleeping bags, for whom the laneways represent something else altogether: a place to rest and a space to use illicit drugs when there is nowhere else to go.

When The Age visits on Thursday, there are half a dozen people camped out among the colourful alcoves of Rutledge Lane, just off Hosier Lane, where crowds are streaming by.

Life is tough living on the streets, but they say this week’s news made their hearts sink. On Tuesday, the state government announced it was abandoning plans to open a safe injecting room in the CBD, which would have been the state’s second after Richmond’s facility opened in 2018.

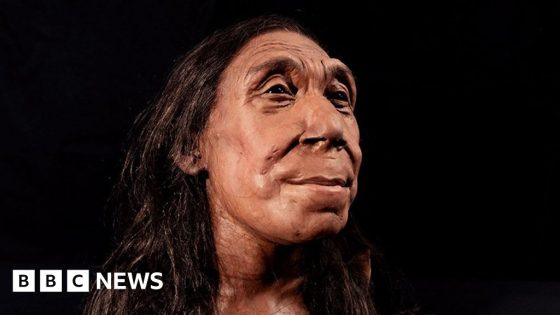

A woman, who is homeless and uses drugs, pictured in Hosier Lane.Credit: Simon Schluter

The decision went against the recommendation of former police commissioner Ken Lay, whose report, released this week, found a “continuing and clear need” for a supervised injecting room. The report identified that the CBD had the highest rate of drug deaths across the state and there had been increases across the board in heroin use, heroin-related deaths and ambulance call-outs.

There had been broad support for a CBD facility, but with each potential location, the idea suffered from a sustained campaign by traders and residents who feared impacts to safety, amenity and anti-social behaviour.

“This issue of the location has been a sticking point,” Premier Jacinta Allan said this week. “We have been unable to find a location that strikes the right balance between supporting people who use drugs with the needs of the broader community.”

In ditching the four-year policy, Allan instead announced a $95 million statewide package to fund more support services, expand opioid replacement therapy and set up vending machines for naloxone, an overdose reversal medicine.

For 41-year-old Wamba Wamba woman Kaz, a heroin user who spends her days and nights in city laneways, this is not good enough. When The Age meets her on Rutledge Lane on Thursday, she is in tears: she has lost five friends since the start of 2024 to a heroin overdoses in the CBD. She believes that if a safe injecting room had been established, they would still be alive.

“The amount of people that I’ve lost this year already,” she says. “Two of them were my best friends.

“It’s just crap they didn’t go ahead with the safe injecting room. We need it, too many of us are dying.”

With her is Kay Bee, who is 25 and already has seen people “drop” many times – the term used for an overdose. She says a CBD facility is needed.

“There is more drug usage here in the city than in Richmond,” she says. “They’ll do heroin down laneways and sometimes people won’t go there for four or five hours.”

A peer harm reduction worker at Hosier Lane health service The Living Room, who asked not to be named due to his other work in the sector, is shattered that there won’t be a second safe injecting room.

Visitors to Hosier Lane stream past the junction of Rutledge Lane where some drug usage occurs.Credit: Simon Schluter

“The decision lost sight of what life is like for people living in crisis, the chaotic nature of their lives and the opportunistic nature of their drug use. That’s why a place that’s open all day, that’s clean and gives support, is so important,” he says.

“Unfortunately the users are not part of this discussion and no one actually hears them … It’s a massive, massive disappointment.”

He says the laneways are where people in crisis feel safe because they’re out of public view. But they also carry a danger: if someone overdoses, who is going to find them?

“We’re pushing people to the margins,” he says. “There’s a reason why people seek out spaces where they won’t be seen; society sees drugs as a legal issue, not a health issue.”

People who work in the sector often point out there is a striking duplicity playing out in our city. In one laneway, people can sip on their glass of wine at a table under a heater. In another, someone is crouched behind a bin on the hard ground to inject, because their substance of choice is illegal.

Baptist Place used to operate as a safe space for drug users. Credit: Simon Schluter

Flinders Court is a laneway so dark and quiet you wouldn’t know that you are just 30 metres from the bustle of Elizabeth Street.

Only the security cameras, at least a dozen of them, give away that this is a laneway that holds secrets in its walls. “You’re under surveillance”, repeats a robotic male voice from a camera flashing blue and red lights.

Nearby, out of view and wedged between two bins, is a young man preparing a needle.

Baptist Place, a small laneway just around the corner from Melbourne Town Hall, used to operate as a “safe space” for heroin users before street lights and a tap were removed to deter drug activity.

It is deserted when The Age visits, with “wet paint” signs fresh on the walls alongside stencils and street art. There is a planning permit application attached to one wall for a new bar.

At the end of Rainbow Alley, a long laneway off Little Collins Street, a bouquet of roses and gerberas lies on the ground near a photo of Danial Korver, a 38-year-old father who died here after an overdose in 2022 and whose family has campaigned for a CBD safe injecting room. Messages are written on the wall. “Merry Christmas. We miss you. Love Mum and Dad.”

A tribute left by the family of Danial Korver who died in Rainbow Alley in the Melbourne CBD in 2022.Credit: Paul Rovere

Last year, the Coroners Court of Victoria published a report finding that 2022 had the highest number of overdose deaths – a total of 549 – than any year in the previous decade. More than half of those deaths involved heroin.

Melbourne is also Australia’s heroin capital, according to the Australian Crime Intelligence Commission. Of the estimated 999 kilograms of heroin consumed nationally in the year to August 2023, almost half was used by Victorians.

Lay’s report found that injecting drug harms were likely to continue to concentrate in Melbourne’s CBD, affecting some of the most vulnerable members of the community.

“Providing medical supervision to people while they inject heroin saves lives because of the unique characteristics of the drug. If a dose is even slightly above a certain level, it can lead to a dramatically reduced heart rate and reduced respiratory rate, causing immediate death if medical interventions are not performed instantly. This is why injecting heroin alone is often fatal.”

Danny Jeffcote, the outreach manager at cohealth’s Victoria Street service near Queen Victoria Market, says his team of 20 workers, who venture on foot to conduct welfare checks, frequently find people overdosed in city laneways.

“It’s not uncommon we’re calling ambulances, it’s unfortunately part of the job. And about once a month we hear another person has passed away,” Jeffcote says.

He says the laneways, in some ways, offer homeless drug users a way of navigating the city safely and quietly.

“A person using drugs has a real dilemma because they need to be able to consume drugs somewhere out of the wind because they’re often mixing up powder, they need light, they need water, but they also need privacy. This is still an illicit drug, so there is the fear of being caught in that very brief moment.”

Danny Jeffcote manages a team of outreach workers at cohealth’s city service.Credit: Luis Enrique Ascui

Jeffcote says heroin users become more likely to inject alone as they get older. But when someone overdoses, they stop breathing, so every minute counts. There is a risk of permanent brain damage even if they survive.

“A safe injecting room wouldn’t be the magic bullet that ends drug use in our city, but it’s part of an ecosystem of a whole range of harm-reduction responses we’d like to see. That solution would be amazing for those who use it,” he says.

As part of Tuesday’s announcement, the government said it would turn the Yooralla building into a $36.4 million health hub run by cohealth, and establish a two-year trial of the opioid-replacement therapy hydromorphone for 60 patients.

Jeffcote says the funding boost will allow his team to grow and work later hours. But after two decades working in the sector, he says it’s time for a frank discussion about drug use and drug law reform. Stigma, he says, is extremely damaging because it creates a cohort of people who are seen as “bad” and feel they don’t deserve the support that anybody else does.

The parents of Danial Korver have campaigned for a safe injecting room in the city.Credit: Paul Rovere

“We’ve had a prohibition system for a long time and we have such enormous drug harm,” he says. “We really need … responses that are wanted by the people who are using them, wanted by their friends and family, and wanted by the broader community.”

The area around Queen Victoria Market is a hotspot for heroin overdoses. A discarded wrapper for a syringe sits just outside the City of Melbourne’s office for the market’s precinct renewal project.

Further along Victoria Street, drug users gather at the small garden space outside the cohealth building.

Michael is disappointed by the Allan government’s decision.Credit: Simon Schluter

Michael, 37, has been using heroin since he was a teenager and says it’s very sad that the government decided to reject the recommendation for an injecting room in the CBD.

“An injecting room would be good in the city and it would do the city well,” he says. “I think it would help clean up the city of the dirty people that use that leave their fits lying around.”

Michael goes to places like the street garden and back alleyways to inject because the Richmond facility is too far away.

He says he hates going into laneways because he worries about seeing someone he knows who has overdosed.

Loading

“The injecting room would have saved a lot of lives.”

Reverend Dr Margaret Mayman, of St Michael’s Uniting Church, says her parish and many others in Melbourne were surrounded by “many little places, nooks and crannies and laneways” where people injected drugs.

“I’m really disappointed that this stigma around injected drugs just continues to drive decisions, in this case, decisions that will cost lives,” she says.

“It’s just closing our eyes to the reality of drug use in the city.”

Mayman says an injecting room would have been a relatively simple, small-scale step to support people who are in great need and would have enriched the city, making it a kinder place for everybody.

“The premier has made a decision, but it won’t be the end of the need.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Source Agencies