The Biden administration has repatriated a family of 10 American citizens who had been stranded for years in desert camps and detention centers in Syria run by a Kurdish-led militia that battled the Islamic State, according to officials.

The government also brought to the United States a pair of half brothers — only one of whom, said to be 7, is an American citizen. The resettlement of the other boy, who is said to be 9, is the first time the United States has taken in someone from the war zone who is not an American national.

The government announced the early Tuesday transfer in a statement from Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken, who said that there had been a “complex repatriation and resettlement” involving 11 American citizens, five of whom were minors, and the “9-year-old non-U.S. citizen sibling of one of the U.S. citizen minors.”

He added: “This is the largest single repatriation of U.S. citizens from northeast Syria to date.”

The statement announcing the transfer did not identify the 12 people. But two officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive details, said 10 were a family The New York Times had reported on in September, consisting of a woman named Brandy Salman and her nine American-born children, ranging from about 6 to about 25.

The other two, the officials said, are the sons — one biological and one adopted — of a man named Abdelhamid Al-Madioum, who was repatriated in 2020 and has pleaded guilty to charges of supporting terrorism. The Star Tribune of Minneapolis reported this month that his two young sons had been found and would soon arrive in Minnesota to be raised by his parents.

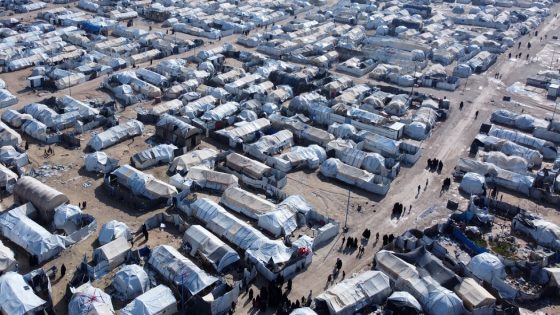

The aftermath of the collapse of the ISIS caliphate — which has continued to carry out terrorist attacks after losing control of its former territory — has led to a festering problem in northeastern Syria, where tens of thousands of people remain effectively imprisoned in the custody of the Kurdish-led militia, the Syrian Democratic Forces.

About 45,000 people are living in the displaced persons camps — mostly women and children. They include roughly 17,000 Syrians, about 18,750 Iraqis and about 9,000 “third-country nationals” from over 60 countries, officials said. The militia is also holding about 8,800 adult men in wartime prisons.

Most of the adult men are suspected of joining the Islamic State, including some who traveled to Syria or Iraq from Europe and the United States. Some brought their families with them.

The United States has been encouraging other countries to take back their nationals — prosecuting them where appropriate — and in some cases providing military logistical help. The same transfer operation that brought the dozen people to the United States also extracted six Canadian citizens, four Dutch citizens and one Finnish citizen who are going home to their respective countries, Mr. Blinken said. Among them are eight children.

Since 2016, when the ISIS caliphate began to crumble, the United States has repatriated 51 American citizens — 30 children and 21 adults, according to the State Department. That number counts the 11 citizens brought in early Tuesday.

Many nations — particularly in Europe — have been reluctant to allow their citizens to return, especially men, fearing that they pose a security threat. Some fear that under their legal systems, any incarceration for joining the Islamic State would last only a few years.

Even small children who were the offspring of ISIS families are often stigmatized. As a result, large numbers of children have been left to grow up under brutal circumstances and are considered vulnerable to radicalization in the camps.

The Times reported last fall that Ms. Salman’s husband, who was from Turkey, apparently took the family into ISIS territory in 2016 and was later killed. Most of the family will now live with her mother in New Hampshire, and the Department of Health and Human Services, working with local social service authorities, has developed a plan to help them integrate into society, the officials said.

However, one of Ms. Salman’s daughters, who is now over 21, will apparently face prosecution for some alleged action in Syria. The woman was arrested when the military plane carrying the group landed at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York early on Tuesday, one official said.

In 2022 and 2023, investigators from Human Rights Watch and the United Nations had separately interviewed one of Ms. Salman’s sons, who is now about 18.

He was then living apart from the rest of his family at what the Kurdish militia describes as a rehabilitation or deradicalization center for youths. Guards had taken him there in early 2020, he told the investigators, as part of a disputed policy of removing boys from the main displaced persons camps, Al Hol and Roj, when they hit puberty.

The teenager told the investigators that his father had tricked the family into going into Syria — telling them they were going camping while in Turkey and only later revealing that they had crossed the border — and that his mother had largely kept the children inside because she was afraid. The Times was unable to verify the details of that account.

The U.N. investigator also said the teenager had expressed “great distress and worry” about his inability to meaningfully communicate with his mother, and showed the investigator paintings and drawings that depicted them together. He also talked about hamburgers and missing rap music, she said.

Human Rights Watch also featured the teenager — obscuring his face and using a pseudonym — in a video about children stranded in Syria after their parents took them there to join ISIS. In it, he said: “It’s not only me. We a lot of kids, you know. No one wants to stay, just like growing up here doing nothing. That’s what we all feeling.”

In the case of the two half brothers, a court filing from the prosecution of their father, Mr. Al-Madioum, said that in 2015, when he was a college student and visiting Morocco with his family, he ran away to join ISIS.

He eventually married the widow of a slain ISIS fighter and himself fought in battle and was grievously wounded, including losing part of an arm. He surrendered in March 2019 to the Kurdish-led militia and was brought back to the United States for prosecution in 2020.

One court filing also mentioned that he was with “his two small children” at the time of his surrender to the militia. But, the officials clarified, only of the boys is Mr. Al-Madioum’s biological son. Mr. Al-Madioum apparently adopted the other boy when marrying their mother, the widow, who was herself apparently later killed.

There are many challenges to transferring people out. The Kurdish militia does not have comprehensive and accurate records about all the people it is holding, and the mixed parentage of many children has further complicated efforts to get countries to take them.

Ian Moss, a deputy coordinator for counterterrorism at the State Department, said in an interview that by taking in the nine-year-old boy who is not an American citizen but has a link to the country through his brother, the United States was seeking to lead by example.

“It’s important for the purpose of reintegration that we don’t split up families,” he said. “And as we continue to work to solve this problem, we need to be thinking creatively about how to preserve family units. Inevitably, that means that — just as the United States has done — countries will need to offer resettlement to individuals who are not their nationals.”

There has been some movement in recent years. In 2022, nearly 3,000 of the displaced people were repatriated — or, in the case of Syrians, returned to their home communities inside the country — more than had left the militia’s custody from 2019 to 2021 combined. In 2023, more than 5,400 people were repatriated or returned to their communities of origin.

“As governments undertake repatriation of their nationals, we urge thoughtfulness and flexibility to ensure to the maximum extent possible that family units remain intact,” Mr. Blinken said.

He added: “The only durable solution to the humanitarian and security crisis in the displaced persons camps and detention facilities in northeast Syria is for countries to repatriate, rehabilitate, reintegrate, and, where appropriate, ensure accountability for wrongdoing.”

Source Agencies