What does an elephant in a British room need to do for his hosts to admit he exists? Under Xi Jinping, China’s rivalry with the free West has become a zero-sum contest. Beijing is engaged in full economic warfare with Britain. And Britain’s establishment, polite as ever, all too often chooses to ignore this inconvenient reality.

Chinese malignity in Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, the Taiwan Straits, Ukraine, the Antarctic icecap and satellite-accessible space has not been enough to dispel the fantasy that our best course is to deepen and strengthen economic relations with Beijing in pursuit of growth, or the idea that we are already so “dependent” upon Chinese goodwill that there is nothing else to be said.

The latest cyberattack on the Ministry of Defence – where the Chinese state is suspected of accessing sensitive data about serving personnel – should be a wakeup call. It is too much to hope that it will be, however. This hack was merely the latest in a long series of direct provocations from the Chinese state undertaken in the belief that Britain is too weak-willed to respond.

From the start of Britain’s trade relations with the People’s Republic of China, Beijing has assiduously cultivated, promoted and paid a stable of high-level supporters in senior political, financial, business, legal, academic and other circles to quietly ease China’s path to access, influence and control of Britain’s wealth and innovative capacity.

This engagement has comprised an integrated campaign of economic, cyber, influence and acquisition warfare, employing methods from the innocuous and open to covert subversion and espionage.

Xi’s ubiquitous slogan of “win-win” is uncannily accurate: in this asymmetric contest, China won twice. In a society where ignorance and naivete about China’s intentions was matched only by increasing acceptance of vast sums of Chinese “investment” in default of sensible levels of government funding, the CCP became both powerful and invisible.

The rot set in early. The Chinese through a charade of signing up to an agreement with the UK to preserve democracy and the rule of law in Hong Kong after the handover. And as soon as the Union flag was lowered, the CCP set about reversing and trampling on everything it had agreed to.

The ineffectual response from Whitehall merely confirmed the idea that power in Britain was the preserve of a an unprincipled elite, whose liberal idealism dwindled as their pension pots grew fuller with Chinese gold.

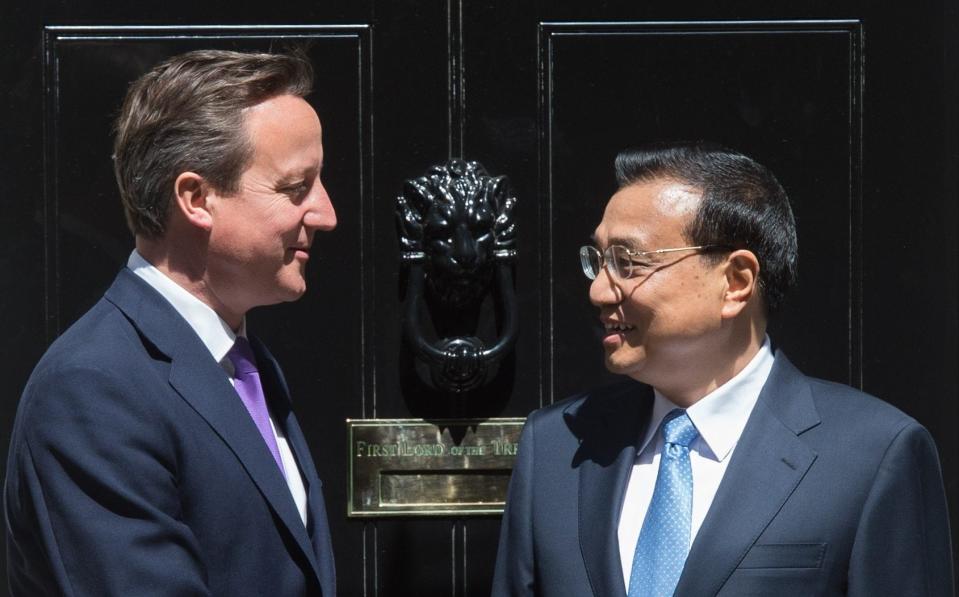

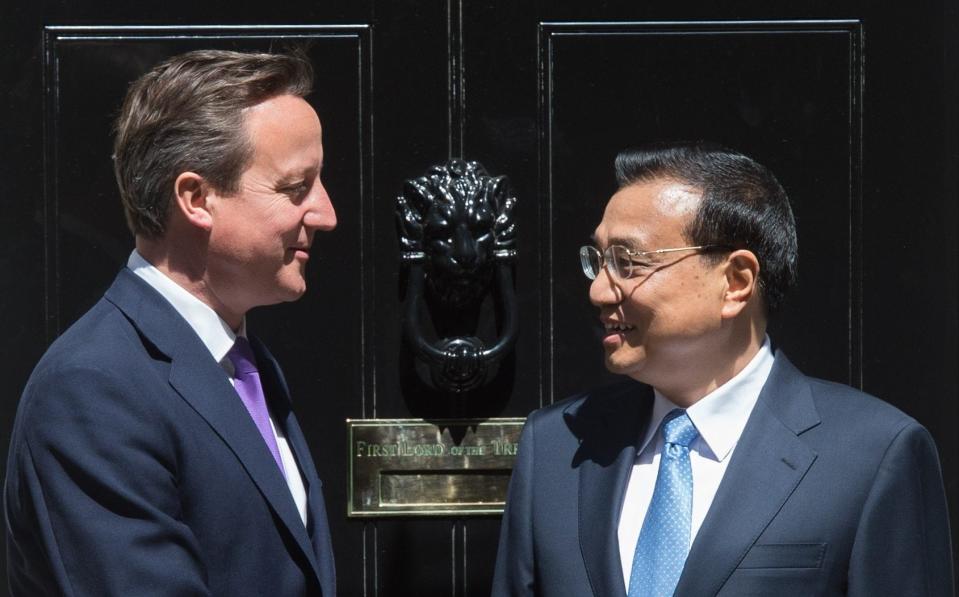

A state which contemptuously dismissed Britain as “an old, declining empire”, and “an old European country good only for travel and study” – the words of the official Chinese newspaper as Prime Minister David Cameron embarked on a trade mission, and welcomed Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in return – was given clearance to finance and build nuclear power stations and operate rail lines in the UK.

The first major reversal in this campaign was the Huawei affair, brought to a head in Britain in 2020, by which time potentially compromised technology would take years to purge from the telecoms system. It took the US sending the former director of CIA and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to hint that intelligence sharing would have to cease for common sense to prevail.

Yet for years before this, and more to follow, Britain and its allies had been subjected to endless cyber attacks, IP theft, coercive mergers and acquisitions, poaching of staff from rival enterprises, patent infractions and a host of other less quantifiable harms. A reality check driven by the behaviour of the CCP around the pandemic caused the tide to turn. But even today, the Government is hesitant to directly name China as a state aggressor.

In the meantime, Beijing has engaged in cyberattacks on British politicians, and may have paid other actors for years of faithful service and support. Chinese-manufactured security cameras have had to be stripped from “sensitive” sites. Universities cosy up to Beijing for funding, even as dual-use research leaks from leading British research facilities.

Of course, China is desperate to steal non-military technology too. Its campaign of economic warfare includes the erosion and destruction of Western rivals to its domestic firms. If a Chinese firm can produce at lower cost a product developed at great expense in the West, the balance of power shifts a little further Eastwards.

The FBI has judged the annual cost to the US economy of such counterfeit goods, pirated software and trade secrets theft at between $225bn and $600bn. Britain does not even know where to begin counting its losses.

It is beyond doubt, however, that the figure is significant. Last year, at Stanford University, the director of the UK’s Security Service told the assembled heads of the “Five Eyes” security and intelligence partners that his operations had recently identified 20,000 approaches to UK individuals by Chinese agents looking for sensitive information. It can be safely assumed that others succeeded; even the largest agency would struggle to cope with attacks on such an industrial scale.

Chinese economic aggression is an omnipresent reality. In far-flung regions of the world, Chinese state actors snap up resources, working towards near total control of the flows of critical minerals that are supposed to power our net zero economy.

On the high seas, the assertion of Chinese sovereignty over the area encompassed by the so-called nine-dash line threatens the critical naval choke points through which half the world’s merchant shipping flows. And in London, Westminster slumbers on, dismissing as bad dreams the warnings of the intelligence community. It is time we woke up.

Source Agencies