Reality Check is a Star series holding those with power to account and shining a light on their decisions. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email our journalists at [email protected].

When Overland Park issued $65 million in STAR bonds in 2012 to build the Prairiefire museum, official documents warned bond buyers the investment came with a “high degree of risk.”

STAR bonds – short for Sales Tax and Revenue – finance major attractions in Kansas designed to spur nearby development. The sales taxes from districts surrounding those attractions pay off the bonds. Kansas is one of just three states with STAR bonds, which are backed solely by future sales tax revenue from the projects.

Last year, the Prairiefire STAR bond project defaulted, unable to make a $15 million payment on time. The project has struggled for years to meet sales tax projections.

Some Kansas lawmakers want to use STAR bonds to finance new stadiums for the Kansas City Chiefs and Royals. After Jackson County voters rejected a county sales tax for the teams in April, a Kansas proposal would authorize STAR bonds with 30-year terms to pay up to 100% of the cost of building a new stadium across the state line.

Fully financing a Chiefs stadium could mean issuing $2-3 billion in STAR bonds, and potentially $1.5 billion to $2 billion for the Royals. Never before have STAR bonds of that size been issued. As of 2020, $1.1 billion total in STAR bonds had been issued in total, according to a state audit. The Chiefs-Royals proposal could triple that.

It is far from certain whether such a massive project could pay for itself solely with sales tax revenue.

Academics and other experts on stadium financing and municipal bonds who spoke to The Star cast strong doubt on whether a Royals or, especially, a Chiefs stadium and surrounding development could produce the sales tax revenue necessary to pay off on time a project 100% financed with STAR bonds. The amount of revenue needed would be significant, and sales taxes can be fickle, fluctuating with the larger economy and the popularity of the teams.

Lawmakers who support using STAR bonds emphasize that taxpayers aren’t on the hook if the projects don’t make enough money to pay back the debt and that Kansas and local governments can’t be forced to raise taxes or make direct payments to pay off the bonds during a default.

While that’s true, experts said it downplays the way a default would make government-issued bonds in Kansas seem less reliable to future investors, which could raise borrowing costs.

And some question whether Kansas would encounter difficulty finding buyers for $3 billion or more in STAR bonds. Many investors evaluate a bond’s credit rating when deciding where to put their money, especially when it comes to multi-billion dollar investments. STAR bonds typically aren’t credit-rated, which could limit the universe of possible investors. If Kansas seeks a rating, it’s possible the bonds would receive a low score.

“If we could fund stadiums by simply building special tax districts for free then we should fund schools like that, we should fund roads like that, we should fund everything like that. And the reason we don’t is that there’s no such thing as a free lunch,” said J.C. Bradbury, a professor at Kennesaw State University in Georgia who has studied sports economics.

“Giving public money to one place necessarily means taking it from somewhere else. So there is a cost here. It may not be obvious but you’re going to end up paying for this and it’s not going to pay for itself.”

How the Kansas proposal would work

Last week during the final two days of the Legislature’s annual session, Rep. Sean Tarwater, a Stilwell Republican who chairs the House Commerce, Labor and Economic Development Committee, unveiled the STAR bonds plan.

It differs in a few important ways from how Kansas has previously used the incentive tool.

In addition to allowing for up to 100% financing – a change from the 50% that’s typical for STAR bond districts – the plan would allow districts to be drawn around team practice facilities as well as the stadiums themselves.

Liquor taxes are typically exempt but in this case, would go toward paying off the STAR bonds. Unlike other STAR bond projects, local governments would not be required to pledge their tax revenue from the projects toward paying back the bonds.

“The structures will bring in the business and they will cause development around them and the sales tax from those developments are what funds those bonds,” Tarwater said last week. “Currently we have a field in Kansas that will be a sports facility one day and the revenue produced by that will pay for the facility over a 30-year period.”

The Kansas Department of Commerce, which would ultimately need to approve any STAR bond project, indicated the agency is highly unlikely to grant a 100% bond-financed project.

“Commerce currently is authorized up to 50% financing but we rarely go over 30%. We would not anticipate authorizing 100% financing, even if allowed,” Patrick Lowry, an agency spokesperson, told The Star.

While Tarwater’s proposal is structured to encourage competition between cities and counties for a stadium, most public discussion has centered on land not far from the Kansas Speedway in Wyandotte County as a possible site for the Chiefs. Whether that site would be viable remains unclear. The Star was unable to reach the landowners for comment last week.

Legislative negotiators agreed to Tarwater’s proposal and it was placed into a bill that would have required the Senate to vote first. But because the Senate never debated the measure before adjourning, the legislative text of the plan wasn’t released publicly. Tarwater didn’t respond to a call on Wednesday.

The plan may reemerge in a special session that Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly is expected to call this summer. While the session will focus on tax policy, lawmakers are free to pass legislation on any topic.

“We just need a little time on it — we’ll be OK,” Senate President Ty Masterson, an Andover Republican, told the Associated Press last week. “I mean, we’re serious about trying to incentivize the Chiefs to come our direction.”

Lowry said the legislative effort to amend the STAR bonds law “could enable us to expand our role as a professional sports state and have another team join Sporting KC in calling Kansas home. Kansas will continue to be ready if and when opportunities present themselves.”

The plan would likely encounter at least some opposition. Americans for Prosperity-Kansas, a group supported by Wichita billionaire Charles Koch, vehemently opposes the STAR bonds.

“STAR Bonds are an egregious form of income redistribution from Kansas families and small businesses to the political class. We see far less competition when we allow Government to pick winners and losers, encouraging private businesses to focus efforts on lobbying government instead of the consumer,” AFP-KS state director Liz Patton said in a statement.

“There are better and cheaper, ways to promote business creation and innovation in Kansas and that’s what we should be focused on instead of subsidizing wasteful projects.”

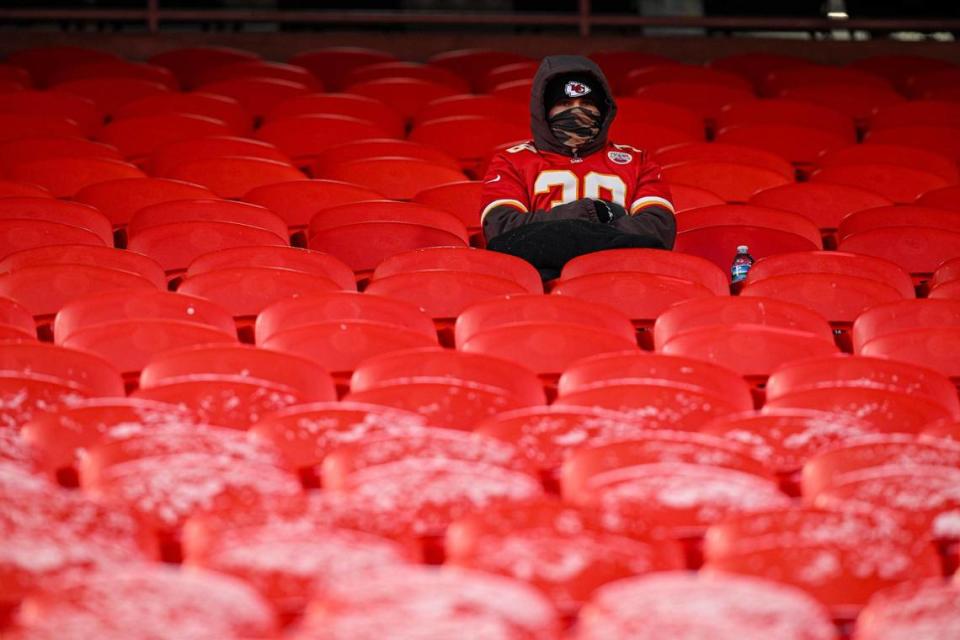

Will the Chiefs stay this good?

Researchers over several decades have consistently found that stadiums and arenas are not major drivers of economic development.

A 2022 review of 130 studies over 30 years conducted by Bradbury and two other researchers found that nearly all empirical studies found “little to no tangible impacts of sports teams and facilities on local economic activity” and that the level of subsidies typically provided for stadiums “far exceeds any observed economic benefits.”

While the review found that any identified economic effects typically occurred in the area immediately surrounding a stadium, those impacts weren’t always present and “can not be generally applied to all stadium projects.”

Geoffrey Propheter, a professor at the University of Colorado-Denver who has studied sports and urban affairs, estimated that $1.5 billion in bonds for the Royals and $2 billion for the Chiefs, along with $500 million in infrastructure improvements needed to accommodate the stadiums, would require annual debt service of roughly $250 million.

Citing surveys of fan spending in the MLB and NFL, he projected concessions, alcohol, merchandise, and tickets would cover about a quarter of the cost of paying back the debt each year. Ten concerts a year at the venues would raise the percentage covered to about a third.

Of course, STAR bonds wouldn’t be paid solely by tax revenue generated within stadiums. The districts would be drawn to encompass new and potentially existing businesses, which would generate their own sales tax revenue.

But Propheter called the districts a double-edged sword, warning that the larger the district the more existing tax revenues are “cannibalized” – or redirected away from funding government services and toward paying off debt. The districts are also more susceptible to the volatility of sales tax than cities or counties as a whole because they cover a smaller area.

The districts also represent a high-stakes bet on the teams themselves and the long-term popularity of the sports.

“The Chiefs aren’t going to be good forever. The Royals aren’t going to be bad forever – we hope. But that ebb and flow means you have to pay this debt service and it’s not going to change unless you refinance,” Propheter said.

Have STAR bonds worked?

In Overland Park’s case, Prairiefire has failed to produce the level of sales tax revenue projected when the bonds were issued in 2012. The 60-acre development – a combination of restaurants, shopping, and a museum – collected about $4.6 million in sales tax revenue last year, but projections offered to bond buyers in 2012 called for more than $5 million a year at this point.

Before the default, state auditors in 2021 estimated it would take Prairiefire until at least 2046 for the state to recoup the sales tax revenue given up by the district. STAR bond supporters caution against using Prairiefire to draw sweeping conclusions about the program, noting the relatively small size of the project.

They say a stadium would fit squarely within the purpose of STAR bonds, which are intended to finance the development of “major commercial, entertainment, and tourism projects.” They point to the first STAR bonds project, the Kansas Speedway, along with Children’s Mercy Park where Sporting KC plays, as successes.

Sen. Pat Pettey, a Kansas City, Kansas, Democrat, and a past Unified Government commissioner, called STAR bonds a “terrific tool.”

“There are all the issues about stadiums about if they actually do turn a profit in any way. And I think that certainly is an issue for future discussions,” Pettey said. “But I think STAR bonds are a perfect tool to look at as long as you have the incentives that can help.”

The Kansas Department of Commerce, which champions the STAR bonds program, has called the program a “very important economic development tool.” In the past, it has emphasized the success of the Village West projects.

“In order to present a fair and balanced perspective on STAR Bonds, Village West provides over $40 million in sales tax to the state general fund every year; has created several billion dollars of private investment; and created tens of thousands of jobs,” Lt. Gov. David Toland, who leads the Department of Commerce, wrote in response to the 2021 state audit.

“Village West’s record of improving both the economy and the general welfare of Wyandotte County and the state as a whole is beyond dispute.”

‘A wink and a nod’

STAR bonds are crafted to severely limit the liability of cities and counties – and the state itself – if a project fails or is unable to produce enough sales tax revenue to pay bondholders on time. While crouched in legalese, the bond documents are full of warnings that investors might not get their money back.

Documents for the Prairiefire bonds include acknowledgments that buyers understand that the bonds have no credit rating and that the “Purchaser acknowledges that the Series 2012 STAR bonds are a speculative investment and that there is a high degree of risk in such investment.”

Buyers are also warned that bonds are “secured only” by revenues from within the STAR bond district and that the bond “will never constitute a general obligation” of Overland Park or Kansas – in other words, bond buyers can never force the city or Kansas to raise taxes or budget funds to pay up.

While that buyer beware language would protect Kansas, and by extension taxpayers, from having to directly pay up if a Chiefs or Royals stadium floundered, it would not shield the state from other consequences of a default if the sales taxes aren’t enough to cover debt payments. A default could risk the credit rating of whoever issued the bonds – whether a city, county or the state – and make future borrowing more expensive.

Justin Marlowe, a professor and the director of the Center for Municipal Finance at the University of Chicago, said a STAR bonds default would risk “contagion,” in which investors would begin to look more critically at other bonds issued by Kansas and local governments in the state.

“A lot of people who buy municipal bonds are buying them, really, at arm’s length. They don’t know all the specifics, all the ins and outs,” Marlowe said. “So if there’s a default, it will naturally raise the question of what’s going on in Kansas – ‘What’s the matter with Kansas?’ to use a bad pun.”

Marlowe said bonds backed solely by a single revenue stream, especially sales taxes, are rare. But Kansas’ endorsement of STAR bonds helps boost their standing in the bond market.

Kansas’ involvement comes with an implicit understanding – Marlowe called it a “wink and a nod” – among investors that even though the bonds are speculative, the state would intervene if necessary to prevent a project from failing and investors not getting paid. That belief among investors stands in sharp contrast to the rhetoric of lawmakers, who dismiss the possibility of risk to taxpayers.

Municipal bonds with higher risk – and higher rates of return – are attractive to some investors. One of the major draws of municipal bonds is that interest income on them is generally exempt from federal income tax in a way that gains on stocks are not, a way of encouraging investors to help finance infrastructure improvements by local governments.

In 2023, states and cities issued roughly $1.8 billion in bonds to finance the construction of professional sports stadiums, according to Bloomberg. But the tax perk of investing in publicly-funded stadium projects could end. Legislation has been previously introduced in Congress that would eliminate the tax exemption for municipal bonds used to finance professional sports stadiums.

A $2-3 billion STAR bond issue to finance one or two stadiums may test the limits of the implied trust between Kansas and bond buyers.

The state or whichever entity issues the bond would face significant pressure to obtain a credit rating for a bond issue that large, in part because investors would demand it. An unrated bond issue that size would be among the largest ever, Marlowe said.

“When you get to that level to generate that much investment, you really need institutional buyers, you really need mutual funds and property-casualty insurance companies and other big investors to come in with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of orders for these bonds,” Marlowe said. “A lot of them are not allowed to buy unrated paper.”

“I think part of the reason that STAR bonds have been generally unrated is because if they were rated … that the rating wouldn’t be very good and may not be investment grade.”

Source Agencies