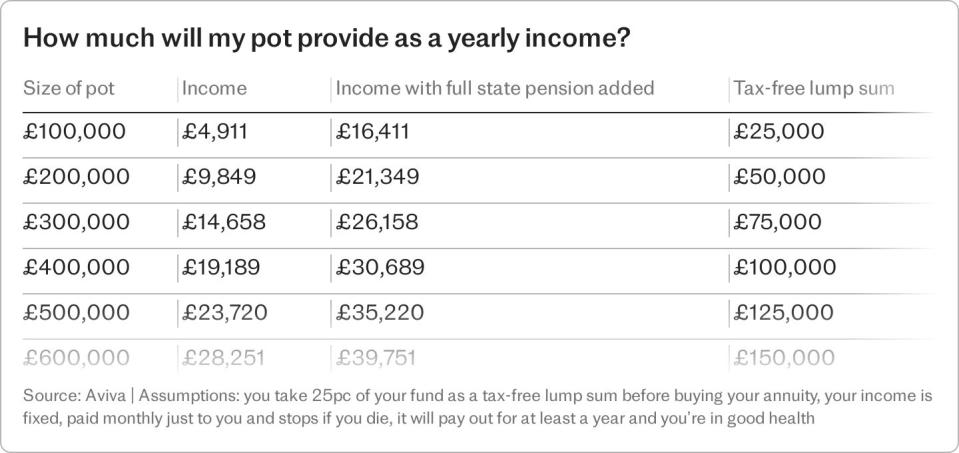

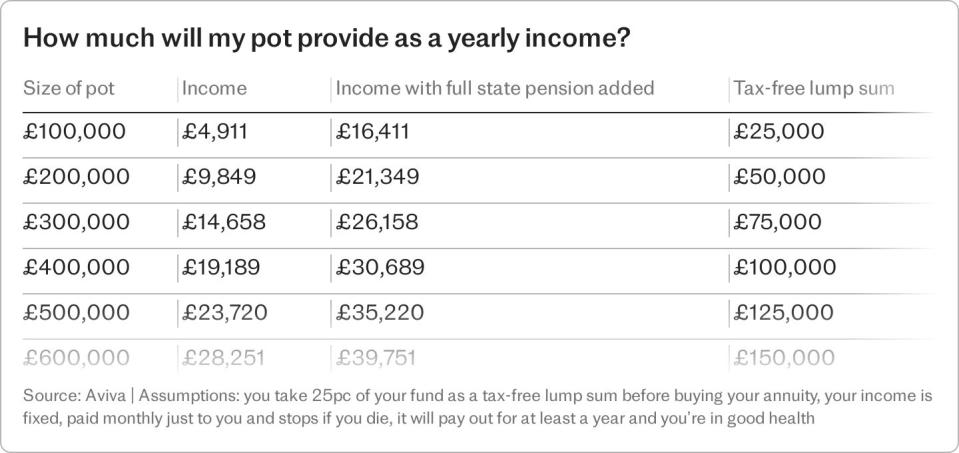

For most savers, the prospect of a guaranteed income until you die would be hard to turn down.

Defined benefit pension schemes (DB) offer an inflation-linked salary in retirement. They are highly sought after, expensive for employers to fund, and increasingly rare. Just 7pc of private sector employees enjoy membership to these gold-plated schemes, compared with over 80pc in the public sector.

But for some intrepid DIY investors, ditching these lucrative benefits has been a gamble that’s paid off. You can swap a guaranteed pension managed by trustees for a “defined contribution” plan where you assume all the risk of generating an income but have far more control and better tax benefits on death.

So-called “transfer values” – the amount you receive in your private pension for giving up the promise of an annual income – are tied to the yield on government bonds. Before interest rates shot up, some people were offered 30 or 40 times the value of their pension to give them up.

‘Finally salary pensions are seen as wonderful – but they’re not’

At 61, Dave Pickett was starting to think about retirement. His gold-plated pension beckoned after a long career working in IT for HSBC.

The defined benefit scheme, based on his final salary, entitled him to a lump sum of £75,000 and £11,266 a year for life, subject to a £1,237 reduction once he hit state pension age.

But he wasn’t convinced. “Everyone says final salary pensions are a wonderful thing – they’re not,” he said. “The guaranteed income equated to 3pc [of the pot] per annum. The average return in the stock market is 6pc.”

His scheme’s inflation-link was capped at 5pc – “not helpful with inflation north of 10pc” – which helped persuade Mr Pickett to take his financial future into his own hands.

He decided to cash out the pension for £425,000, and invest the money himself. After settling some outstanding debts, he was left with a retirement pot of £355,000.

“Without question, taking the lump sum is the best decision we made.

“Hilariously, a lot of the senior managers at HSBC wouldn’t do it [cash out their own pensions] because they couldn’t manage their own money after spending a lifetime telling other people how to do it.”

Mr Pickett, who lives in the village of Newick, near Lewes, East Sussex, has been managing his own portfolio ever since.

He started by investing in 15 stocks, but later switched to several big funds which yielded greater returns.

For the first few years of his retirement, Mr Pickett, 70, and his wife Molly, 67, drew a generous £35,000 from the fund annually, triple what he would have received had he stuck with his DB pension.

“This made a massive difference to our quality of life, as you can imagine. It was always the intention to milk the fund in the early years, when you need money most as you are most active.

“All the financial advisers would tell you ‘you have to live off the natural yield’, but that’s nonsense as you want the money when you’re younger and more able to do things with it.”

Almost a decade later, over half of the original pot still remains. The couple now each draw the state pension and another small defined benefit pension paying £250 a month, which has allowed them to reduce their yearly withdrawals from the fund to £12,000, while still maintaining a “very comfortable” lifestyle.

“If we had only been on £11,000 a year from the start, my wife would have had to get rid of the horse and we wouldn’t have been able to afford to go and do things. We have two sensible cars and two sports cars – a Mercedes SLK and a Mazda MX5.”

The additional income has also allowed Mr Pickett to amass a collection of 30 radio-controlled model planes which he flies at a nearby airfield with a gang of like-minded enthusiasts.

“With hobbies like this, one half is the fun of flying, the other is getting out and mixing with people. A lot of older people suffer from not having social contact, but that’s not a problem for us.”

Despite having shunned the security of a guaranteed income, he never feels anxious about his investments.

“The secret to anything being stress-free is to be in control of it. I’ve learnt that nobody looks after your money as well as you do, and you have to monitor your investments, which clearly many people fail to do.”

‘I cashed in at peak time to draw £1.5m’

Forfeiting a final salary pension package is usually considered a high-risk move. Anyone wanting to transfer a pension offering guaranteed income with a transfer value of more than £30,000 is legally required to seek regulated financial advice before being allowed to do so. In Mr Pickett’s case this cost him £1,500.

In practice, the rule limits the ability of some savers with small pensions to transfer them, as most financial advisers will only consider offering advice on pots of at least £150,000.

However, the Department for Work and Pensions is considering raising the advice threshold to £100,000 in order to unlock transfers for those with smaller defined benefit nest eggs.

For those with bigger pots, this isn’t an issue. After working for 30 years as a Sainsbury’s store manager, Simon Lean, 58, had amassed a generous final salary pension, equating to £37,000 a year for life.

But his pension provider was incentivising members to transfer their pensions elsewhere in order to remove the expensive lifelong obligations from their books. Mr Lean was intrigued.

His scheme offered him a cash equivalent transfer value (CETV) – a lump sum figure to transfer his pension – which “shot up hugely” in the years before he decided to retire, aged 55.

“Some years it went up by £200,000 to £250,000,” he said. By the time he took the plunge, the transfer value had risen to more than £1.5m.

“It was perfect timing. My financial adviser told me that since I cashed out, the transfer value of funds has reduced by 45pc to 50pc.”

The money went into a self-invested personal pension (Sipp) with True Potential wealth management and then Prudential. But a turbulent market meant the promised returns didn’t materialise. The stress of seeing his life savings fluctuate also took its toll.

“In the first week I was up £10,000 but other weeks I’d be down £60,000. I was like ‘woah’. I tried not to look too frequently, but it was stressful.”

He decided to simplify things and transfer his full retirement pot into cash within his Sipp. With an interest rate of 5.1pc – just below the Bank of England Bank Rate – he draws an annual pre-tax income of £49,000 after fees.

“It takes me up basically to the higher rate tax bracket. While the Bank Rate stays high I’m more than happy. That gives me no risk and what I need to cover my living.”

His ambition was to build a house in St David’s, on the bucolic south-west tip of Wales, with his wife, 55, a yoga teacher.

He used drawdown to access the maximum amount of tax-free cash he could – £268,275 – and kept the rest of his pot invested. This gave him the funds to buy a plot of land and fund the building work on their eco-friendly dream home.

The couple installed an air source heat pump and solar panels with battery storage. They also bought a new car. “I thought to myself, I’ve got all the kit, so I may as well buy a Tesla.”

Mr Lean is “delighted” he decided to transfer out of his defined benefit pension. “If I had stayed with Sainsbury’s and I had died, God forbid, my wife would have only got half of my pension. It just made sense to transfer it. The fund is ours.

“We’ve got no mortgage, no debts, no credit cards and we have the proceeds from our previous house. It allows us to enjoy the countryside and enjoy life.

“We go on lots of coastal walks. I’m due to have hip surgery, so the extra income is funding repairs to my life.

“I’m very fortunate. I retired at 55 and am free of any concerns about market fluctuations. Of course this is dependent on the Bank Rate staying high, but for the moment, it’s working out nicely.”

Source Agencies