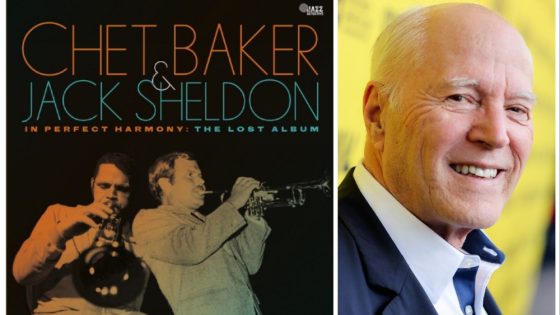

Lost, completed studio albums by revered trumpet player and jazz vocalist Chet Baker don’t pop up every year. But “In Perfect Harmony: The Lost Album,” which was just released after sitting unheard for 52 years, has some even more novel wrinkles to it. For one, the previously unreleased 11-song set is a full-on collaboration with a second trumpeter-singer, Jack Sheldon — who may be best known to fans of a certain age as a familiar voice from the “Schoolhouse Rock” television show’s songs. Although Baker and Sheldon were pals who played together live, this newly unearthed project marks the only time they ever went into the studio together to make an album.

But here’s maybe the biggest novelty of them all: a co-producer on the new release is Frank Marshall, the famous film producer who’s known for some of history’s biggest movie franchises, including the Indiana Jones, “Jurassic Park” and Jason Bourne tentpole series. Marshall might seem like an unlikely choice to suddenly dip his toe into releasing archival jazz, but there’s a sound explanation: His father, Jack Marshall, was a well-known jazz musician and Hollywood composer who played guitar on the sessions, and who co-owned the Orange County studio where the lost album was cut. Marshall had it in the back of his mind for many years to play the tape he’d come across in storage that was marked “Chet and Jack,” but never did until two years ago, when he realized he had a serious find on his hands.

Marshall’s partners on the project include Zev Feldman, the founder of Jazz Detective Records, as well as a significant figure for his work with the Resonance and Elemental labels, which specialize in just this kind of reclamation work. “In Perfect Harmony: The Lost Album” was released in an elaborate vinyl package for Record Store Day last month, and that LP was followed later by a just-as-elaborate but more compact CD edition.

Marshall spoke with Variety about being convinced by Jeff Pollack (also a film/TV producer, and an executive producer on this set) that there was someone out there who could do something with this amazing score. Baker cultists will be particularly interested in it because it comes from a period in which Baker was believed not to have recorded any studio sessions at all, due to his anxiety about wearing dentures after taking a beating. It fills in a crucial piece of Baker history. But possibly just as interesting is Jack Marshall’s own history of work before he died of a heart attack on Sept. 20, 1973, leaving the tape in limbo; his son shares a bit about what it was like to grow up with one of SoCal’s more revered musicians in the ’60s and early ’70s.

Let’s talk about the provenance of the tape. Zev Feldman is at the forefront of doing archeology to find tapes of jazz shows or studio sessions from decades past that never got released. So he must have been extremely interested to hear about this recording.

“The jazz detective” is a perfect description of Zev, because detective work was an apt description of what we went through to try and put this all together.

Was this a tape you knew was sitting around, or did you stumble upon it?

No, I knew it existed. It’s been in a box for a long time, and it’s that thing that you say, “Oh, I’ll get to this,” and you just keep putting it aside. It was the ‘70s when my dad passed away suddenly, and there was no archive and there were just things in the garage. And then as life goes on and the family moves — and we sold the house. and the boxes got moved, and my brothers took some and my sister took some and I took some — the album never really got put together, to be honest.

There was this little recording studio up in Tustin called United Audio that my dad and somebody else that lived near us on Lido Isle opened, and my dad did a lot of recording there. He always said it was a lot easier to drive to Tustin than all the way up to the Valley, where most of the recording studios were. When this album got put together, I was off starting my filmmaking career, so I wasn’t around when they did the recordings. Jack Sheldon was my dad’s best friend, and obviously Jack and and Chet Baker were good friends, and so they put together this little album on a shoestring…

At a point in Chet Baker’s career where he otherwise wasn’t really even going into the studio, right?

It was the first time that Chet had really tried to make a comeback, it turns out, which I never thought about until a couple years ago, when I was talking to Zev and he said, “Oh, this is an earlier recording than the first one that we knew about” [after Baker had taken years off]. So, suddenly it became really valuable.

And we’ve been trying to track down for a couple of years who was on it and how it got put together, when there was no paperwork. The co-owner of United Audio, Hank Quinn, has passed on, so it took his son and myself to try and dig through and put together this puzzle of how this all came about. We didn’t even have the records of who was playing on it. Except I knew my dad played on it, and we knew Chet and Jack played on it, of course, but we had to do some detective work on our own to figure out who else was playing. [What they eventually found was that, besides Baker, Sheldon and Marshall, the sessions included pianist Dave Frishberg (who later wrote some of the songs Sheldon sang on “Schoolhouse Rock”), bassist Joe Mondragon and drummer Nick Ceroli.]

In the liner notes, it sounds like Baker’s and Shelton’s intentions for the recording are a little bit mysterious. Is it clear that they were really making an album that was intended for release, and then it just got abandoned?

Yes. It was sort of the start of the independent record period, and they were putting together their own album. As I recall, it was still the day of the big record companies, but they didn’t want to release through a big record company because they took all the profits and took everything. So they were gonna make a sort of hometown jazz album and then either release it on their own or go with one of these little boutique record companies that were starting to blossom up — I think they were intending to release it that way. But then when my dad passed, there was nobody as a driving force to take it out and get it released.

The liner notes go into detail about where exactly Chet Baker was at that time. He very insecure about his teeth and didn’t record for something like five years or more before this project — is that right?

Yeah. He was very insecure, and he and Jack Sheldon were very good friends, and I think Jack kind of coaxed him back into the studio. Just to make him comfortable, he said something like, “Hey, you only have to play on half the album if I’m there.” So it was a real family situation. Since my dad and Jack were best friends, and Chet and Jack were very close friends, it was much more of a rehabilitation, and trying to get him back into the mainstream. There was a lot of love, I think, involved in the whole thing.

So that comeback did happen for Baker, but it was one or two years after this. So this might have served as some kind of baby step for Chet kind of getting back into things, at least psychologically. How much did those two guys, Baker and Sheldon, do together?

They played live together, but this is the only album that I know of that they’re both playing together, which is kind of amazing when you think about it.

How did you get hooked up with Zev Feldman to start doing the research and everything on this?

It was through Jeff Pollock; he’s a good friend, and a huge music historian. I played him this album because our daughters were friends — that’s how it started, at school. And he says, “Well, we, we have to get this out. We have to figure out a way to release this.” I said, “No, no, no. Too complicated.’ So he’s the one that introduced me to Zev and said, “I think I’ve found the guy that can pull this all together. He’s known as the jazz detective.”

What shape were the tapes in? Was there more than one copy?

Yeah, there were different tapes and I just happened to have (a master), from when we tossed everything from our house down in Newport Beach down into a box and put it in archives. There I found a box with a handwritten thing on it, “Chet and Jack,” and I thought, this is it. Somehow they each got a quarter-inch tape. I’ve talked to the son of Hank Quinn, who owned United Audio, and he thought he had a master, but he didn’t. He had another quarter-inch that wasn’t as in good shape as mine. So we used my quarter-inch as the master.

It’s fascinating that your family moved down to Newport Beach, which is a fine place to move, but could indeed be a drag to be driving up to Hollywood on a regular basis to work as a studio musician.

Well, it is crazy. But there really were a lot of jazz musicians who moved down to Newport. There was a place called the Villa Marina that used to have live jazz on a Sunday, right across from Balboa Island. And there was a trombone player that my dad worked with named Joe Howard. And a lot of musicians liked power boats. They kept them down in Wilmington, and then in Newport and Joe Howard had a boat and he was in Bay Shores down there, and my dad loved it down there. We used to go down there every Easter when I was a kid; my parents loved it there. And even Johnny Mercer lived on where we moved to, so there was this whole jazz connection down there in Newport.

And then, this family that we knew, the Quinns, were always over at the house. And then Hank decided he was an engineer and he decided to build this little studio in a strip mall up in Tustin, which was only 20 minutes away from Newport. There was a lot of business because Orange County was starting to grow, and there were a lot bands who wanted to do their demos or whatever, and he had a big board. So they did this whole album down there.

Just to give people a sense of perspective about your dad: He had solo albums on Capitol, and so forth, as well as his sideman career as well, and then he had a career doing things like the “Munsters” theme and some score work. When you were growing up, how famous did he seem to you? And what’s your sense now of how well known he was — was he one of those kind of hidden treasures, or was he pretty well known?

He’s a little bit of both. I was always amazed that he would, he would sit at the piano in our house down in Newport, and he had this gift … There was big yellow music paper that would be on the piano, and down the left side would go trumpets, clarinets, trombones, violins. And he would play a chord on the piano with his left hand, and he would write the notes that he could hear in his head. He was so gifted musically, with a very mathematical mind. And music is very mathematical, and he would be able to write those parts down for this big score. I was just always amazed.

And there was music in our house all the time. It is really fascinating to me to look back now and remember what it was like at our house in Newport, where it was kind of an open door policy with musicians coming and staying and playing. Also, we had guitar Saturdays, where anybody could come over with a guitar and my dad would teach and show them chords in whatever styles they wanted. And we would have a big jam session at the end of the day. We used to have these jam sessions at our house, and can you imagine? All these incredible players, and Johnny Mercer comes over and he’s sitting in? It was just an incredible time.

When I look back now, he was a big favorite of all the musicians, because he was able to conduct and write, and he always had a sense of humor, so they loved him.

He goofed around a lot, sometimes probably too much. But with friends like Jack Sheldon and Shelly Mann and Howard Roberts, they would come over on the weekend and everybody just loved to play together. There was no “We gotta make money, we gotta have a deal.” Then he started guitar night at Dante’s, the jazz club up in North Hollywood, so everybody could just play for scale and play together. So he was very beloved in the musical community and he was able to get people together.

And that’s what he did on this album, where they were nursing…. Now when I look back, they were nursing Chet back to playing.

Jack Sheldon has his own cult, of coure — it’s not just Chet Baker. Fans will be interested in this little link between the eras.

I think so. When you look at the tunes that they picked, it was pretty much jazz standards, some bossa nova in there, and a couple of original blues numbers where they could just play. But they kept it kind of commercial.

You’re known as a music lover, which your recent history of documentaries proves to anyone, from the Bee Gees film to the upcoming Beach Boys doc. It’s easy to see how you got a good jumpstart in your love of music. Are you a jazz nut yourself, or just more of a general appreciator of all music?

I wouldn’t say a nut. Jazz is where I grew up. My dad always thought that if I played the guitar…they didn’t force it on me, but it was always in the house. And when I started playing, my dad said, “If you learn classical guitar, you can play anything, because you can read and you have the finger dexterity,” so I learned classical guitar. I have a cousin, Chris Parkening, who took that to a whole different level, because of my dad. [Christopher Parkening is one of the world’s more renowned classical guitarists.]

But I would say that I’m a traditional jazz aficionado. I’m not a modern jazz aficionado. I like the basic “We play the melody, then we do our improvisation, and we come back to the melody.” That’s how I grew up. That’s also what Howard Roberts, another one of my dad’s great friends… that’s was my influence. So I’m not a nut, but I’m a big jazz fan.

For anybody who wants to listen to what your dad was about, is there album that you would point people toward that you think sort of best shows what he was about as a jazz player?

Sure. He did four or five albums. I think his very first one, which was called “18th Century Jazz,” is sort of in his style where he would take traditional songs and jazz them up, shall we say, but with chords and a style that was really him. [The album, Marshall’s solo LP debut, came out on Capitol in 1959.] He did an album with Shelly Manne, actually, called “Sounds Unheard Of!,” which is him playing finger-style guitar and Shelly just doing weird percussive sounds and cymbals and things, and it’s fascinating. [This collaborative project was released on Contemporary Records in 1962.] “Sounds Unheard Of!” is probably one that shows my dad at his finest, as both a player and an arranger, with Shelly Manne.

Source Agencies