Lockheed Martin has test-fired a Patriot PAC-3 MSE interceptor from a Mk 41 Vertical Launch System-derived containerized launcher and used it to down a mock cruise missile. This combination offers a valuable additional air and missile defense option for use in a slew of existing and future launchers, and not just on ships. It is also one that might help, in part, address broader growing concerns within the U.S. Navy about keeping up a steady supply of surface-to-air and other missiles during a future high-end conflict, such as one in the Pacific against China. The War Zone explored this issue in depth earlier this year in the context of the future Constellation class frigate and its planned arsenal.

A Mk-41-derived four-cell Mk 70-series containerized launcher was used to fire the PAC-3 MSE interceptor during the recent test, according to a press release Lockheed Martin put out today. A modular and scalable version of the company’s combat-proven Aegis Combat System, called the Virtualized Aegis Weapon System, was also used to execute the launch. Like its parent system, Virtualized Aegis can be networked together with various weapon systems and sensors, and you read more about the entire Aegis family in this past War Zone feature.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dMUfDCrxR2U

The Lockheed Martin press release says that the test was conducted in “partnership with multiple Department of Defense Services and Components,” but does not name them. In January, Breaking Defense reported that the U.S. Navy was among those set to participate.

What sensor or sensors were used to cue the PAC-3 MSE (Missile Segment Enhancement) to intercept the mock cruise missile in the test are unknown. These missiles are currently only used in the Patriot surface-to-air missile system and are directed first by its fire control radar.

Lockheed Martin also says that it “validated” the PAC-3 MSE’s ability to communicate with an AN/SPY-1-series radar using Aegis last June. In the U.S. Navy, AN/SPY-1 radar variants are the main sensors linked to the Aegis Combat Systems on Ticonderoga class cruisers and, at the time of writing, all but one of its Arleigh Burke class destroyers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GxB0ZqEIY4E

As designed, the PAC-3 MSE, as well as earlier PAC-3 types, uses whatever initial cueing it receives to fly first to a designated point where the intended target is projected to be headed using its built-in inertial navigation system guidance package. Mid-course guidance updates are provided to the missile via datalink. Once it arrives at the set location, the interceptor switches over to its active radar seeker. You can read more about the PAC-3 MSE and how it differs from previous missiles in that series here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xU9C2iLm764

The PAC-3 MSE and its predecessors are designed to function as hit-to-kill interceptors, meaning that they destroy their targets through sheer force of impact. However, they also have a relatively small explosive warhead called a “lethality enhancer” that is designed primarily to eject a number of metal fragments known as “cycloids.” This, in turn, creates a larger physical mass for the target to slam into, increasing the probability of a successful intercept, especially against smaller targets like cruise missiles or aircraft. PAC-3-series interceptors can also engage incoming ballistic missiles, which are generally larger targets, in the terminal stages of their flights. You can read more about the PAC-3’s lethality enhancer in this past War Zone piece.

![A general overview of the improvements found on the PAC-3 MSE variant over earlier PAC-3 interceptors, including a "New LE [lethality enhancer]." <em>Lockheed Martin</em>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/QMQsSfhEMkGaoUrpwVJJXA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTUzMw--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_warzone_735/4a2675d00866eae03ff69661d2b07af4)

It’s worth noting here that the U.S. military views cruise missiles as a particularly concerning threat category at present, both when it comes to forces in the field and potential targets within the homeland. Near-peer competitors like China and Russia are developing and fielding ever more advanced air, sea, and ground-launched types, including ones claiming to boast hypersonic speeds. Lower-tier, but still very capable cruise missiles also proliferating more and more among smaller countries and even non-state actors.

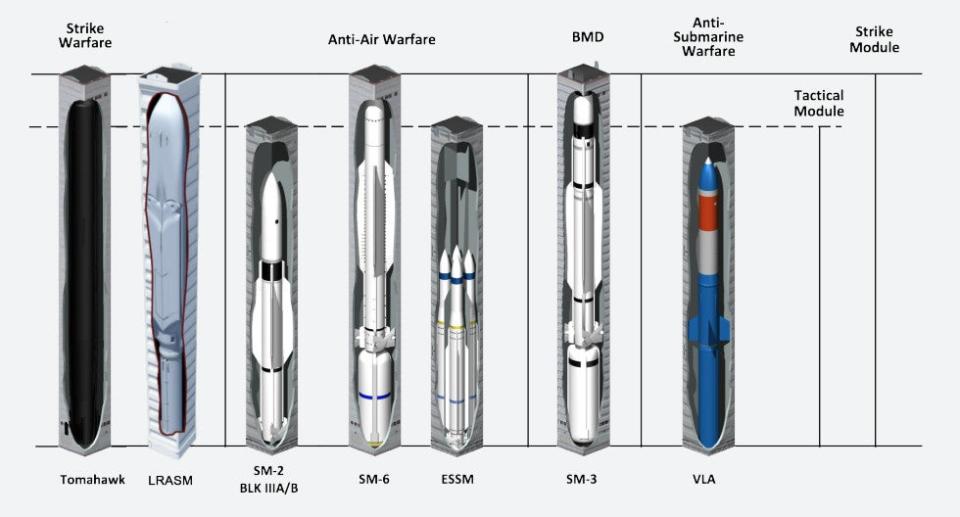

Being able to fire PAC-3 MSEs, the latest and most capable variants in the PAC-3 line, and one that is very much in production, from any Mk-41-based launch system is significant in itself.

Beyond Mk 41 VLSs integrated on ships, this includes BAE Systems modular Adaptable Deck Launching System, which is an angled deck-mounted launcher for ships designed to fire missiles loaded in the same standardized canisters used in the Mk 41 VLS.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bh_FKnf3lbw

Lockheed Martin has also previously said that the PAC-3 MSE is small enough to fit in shorter tactical-length versions of the Mk 41, further expanding the potential array of existing U.S. and foreign platforms that these interceptors could be integrated into. Pairing this capability with Virtualized Aegis offers additional flexibility in terms of integration, as well as operational use depending on what else the entire system is tied in with.

By using the Mk 70-series containerized launcher in its test, Lockheed Martin has also demonstrated the ability for this capability to be readily added to various platforms at sea and on land. The U.S. Navy has previously launched multi-purpose SM-6 missiles – a weapon we will come back to later – from Mk 70-type launchers installed on crewed and uncrewed ships. The service also now has a trailer-based version of the system for use on land, but it is unclear if that combination has been live-fired in testing or training. Since they are Mk 41-based systems, Mk 70 launchers can fire other missiles beyond SM-6, too.

The U.S. Army is also in the process of fielding a ground-based missile launch system, called Typhon, which uses Mk 41-based launchers that are functionally identical to the Mk 70, as well as an Aegis-derived fire control architecture. Typhon is designed to fire SM-6s, as well as Tomahawk cruise missiles, but it might be attractive for the Army to also have the option to fire PAC-3 MSEs from the same launchers. The size of the service’s Patriot force at present, which is in persistently high demand, is worryingly small and there is a clear need to bolster its longer-range air and missile defense capabilities. Raytheon makes both the SM-6 and Tomahawk series missiles.

The U.S. Marine Corps is also moving ahead with plans to field a ground-based Tomahawk capability that uses a single-cell Mk 41-based launcher mounted on an uncrewed derivative of the 4×4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV).

At the same time, some of the biggest benefits of the PAC-3 MSE/Mk 41 may be logistical. Lockheed Martin has been publicly pitching this concept since last year and has presented it as a potential complement rather than a competitor to existing missile options for the Mk 41, especially the SM-6. The SM-6 family was originally designed primarily as a surface-to-air missile, but it has a demonstrated capability against ballistic missiles and novel hypersonic threats in the terminal stages of their flight. On top of that, SM-6s can be used as quasi-ballistic missiles to engage ships and other surface targets.

In an interview with Breaking Defense in January, Thomas Copeman, Vice President of Strategy and Naval Systems at Lockheed Martin’s Missiles and Fire Control business unit, specifically talked about how mixing PAC-3 MSEs and SM-6s together could make it easier for the Navy to keep the latter missiles in reserve for scenarios requiring their unique “offensive” capabilities. Adding PAC-3 MSEs to the available options could offer benefits in the optimizing of the loadout of a single Mk 41 array unrelated to the SM-6, too.

Though it is assumed that Copeman was talking about Navy missile employ in a shipboard context, the service has indicated in the past that it could use Mk 70s loaded with SM-6s in surface-to-surface strike and/or air defense roles in the future. To date, the U.S. Army has only said it plans to use Typhon to fire SM-6s against surface targets.

There is only a slight cost differential between the two missiles, according to the Pentagon’s 2025 Fiscal Year budget request. The price of a single SM-6 Block IA, the most advanced variant of the missile in production currently, is nearly $4.3 million, according to Navy budget documents. The Army’s portion of the proposed budget or the next fiscal cycle puts the price of a single PAC-3 MSE at almost $4.2 million.

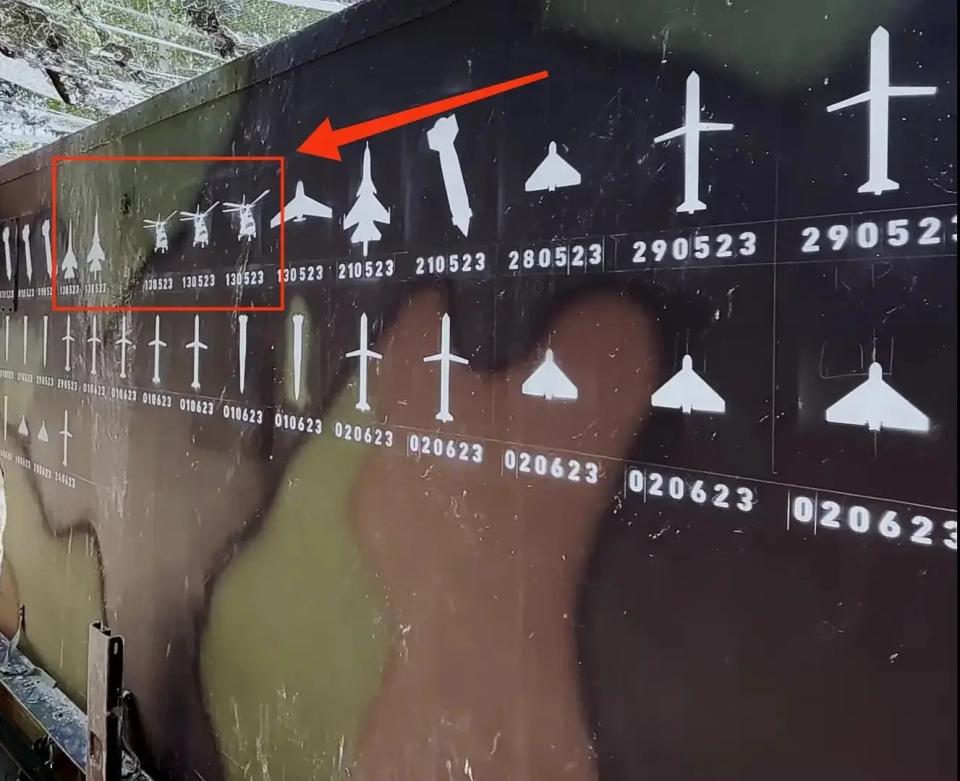

Beyond all this, as already pointed out, PAC-3 MSE is in very active production, and demand for it from Patriot operators around the world has only increased in recent years. This is in part due to the very successful performance of Patriot systems in Ukraine using PAC-3 interceptors, as well as older PAC-2 types, against a wide array of threats, including ballistic missiles. Lockheed Martin is now making significant investments to meet a goal of expanding its annual production rate of PAC-3 MSEs from 500 to 650 by 2027.

Just having another source of in-production interceptors to load into empty cells in Mk 41-based launchers could be very beneficial. U.S. military efforts since October 2023 to protect international shipping lanes in and around the Red Sea from ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as drones, launched by Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen have required a significant expenditure of munitions. Over the past eight months or so, U.S. forces in the region have also struck Houthi assets ashore and defended Israel from an unprecedented barrage of Iranian missiles and drones.

As of February, the U.S. Navy alone had fired over 100 Standard-series missiles in the course of those operations, including SM-6 and SM-2 types. The service employed extremely expensive SM-3-series ballistic missile interceptors in combat for the first time in the defense of Israel in April. That same month, Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro said his service had expended nearly $1 billion worth of missiles overall in operations against the Houthis and to defend Israel. All currently produced missiles in the Standard family are made by Raytheon.

The Navy is working to replenish its stocks, but significant questions remain about how long that process might take. This raises additional concerns about what might happen in a larger-scale conflict, such as in the Pacific against China, where the expected volume of missile expenditures would be even greater.

All of this only underscores the potential value of having another stream of interceptors to load into the cells of Mk 41-based launchers. It’s worth noting that U.S. Army Patriot systems were also involved in the defense of Israel in April.

There is a separately pressing question about how the Navy, which currently has no at-sea arming capability, would physically do that loading, especially in contested environments, an issue you can learn more about here.

For Lockheed Martin, combining PAC-3 MSE with the Mk 41 presents a potential way to break Raytheon’s long-standing lock on naval missile sales.

Altogether, the demonstration of not just the ability to fire a PAC-3 MSE interceptor from a Mk 41-based launcher, but also successfully bring down a mock cruise missile, looks set to open many doors to interest in what this combination might offer.

Contact the author: [email protected]

Source Agencies