A pack of kids lined up for lunch at Centennial Elementary School in Nampa, eagerly waiting for a teacher to give the sign before they launched into the cafeteria.

They grabbed their friends, piled peaches onto trays and swung packed lunch boxes onto tables before chowing down in the 1970s-era cafeteria that had served generations of Nampans.

But soon the cafeteria will go quiet. The school’s doors will no longer swing open into hallways filled with paintings and cardboard science presentations. The books will be removed from the central library, and streamers hanging from the ceiling will be taken down.

On the final day of school at the end of May, the Nampa School District will close Centennial permanently in response to financial pressures and a decrease in enrollment despite significant population growth in Nampa. The district will also close or repurpose Snake River Elementary, Greenhurst Elementary and West Middle schools.

Nampa is not an outlier. The Treasure Valley has ballooned in population in the last 10 to 20 years, yet student enrollment in many of the region’s school districts has either decreased or become stagnant since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 — posing threats to the stability of the region’s public education system.

Some of the largest districts in the region have seen both historical and recent stagnation or declines, including Boise, Nampa and Caldwell.

Shifting Treasure Valley enrollment numbers

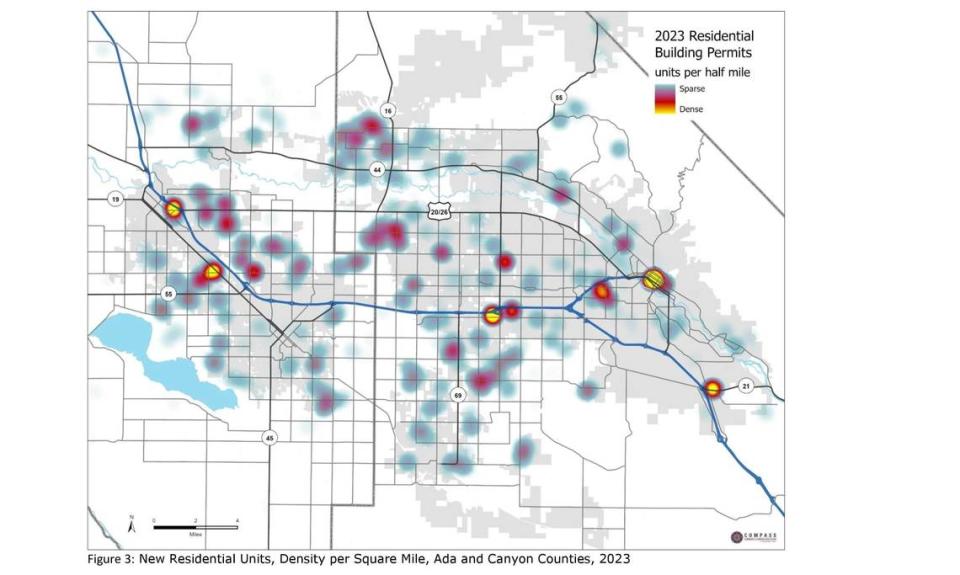

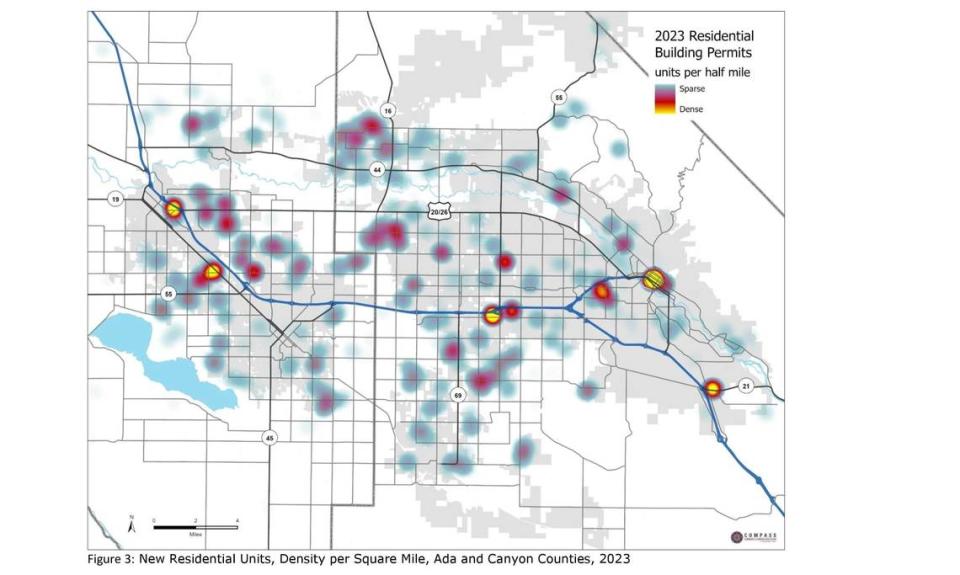

Most Treasure Valley districts have suffered shrinking enrollment since the COVID-19 pandemic despite significant increases in population, according to population data from the Community Planning Association of Southwest Idaho, or Compass, and enrollment data from the Idaho Department of Education.

Since the 2019-20 school year, West Ada has lost 1,633 students and Boise 3,002. Nampa has lost 884 and Caldwell 740. Those four districts have lost a combined total exceeding 6,000 students.

Smaller districts including Notus, Melba and Parma in Canyon County have also lost students.

There are some exceptions. Vallivue has added 474 students, Middleton 273 and Kuna 195.

Overall, Canyon and Ada counties gained over 75,000 new residents from 2020 through 2023 and lost nearly 5,500 students.

Why?

Much of the mismatch between population growth and school enrollment comes from the region’s shifting demographics as older generations without school-aged children migrate to Idaho.

“The most starkly contrasted example of that (is) in the Treasure Valley,” said Ryan Cantrell, chief deputy superintendent for the Idaho Department of Education.

The Valley is growing older fast as retirement-age adults move here. Ada County’s median age has climbed faster than the national average, to 39.1 in 2022 from 32.8 in 2000, a rise of more than six years compared with less than four nationwide, Compass data shows. In Meridian, the median age rose more than 8½ years to 38.7 from 30.1. In Eagle, which falls within the West Ada district, the median rose over 11½ years to 46.8 from 35.2.

The share of people 55 or older in Ada County grew to 27.4% in 2022 from 26.6% in 2020, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates. In Canyon County, it grew to 25% from 24.4%.

According to Quinn Perry, deputy director of policy and government affairs for the Idaho School Boards Association, it’s not young families moving to Idaho, it’s mostly retirees who can better afford today’s high housing prices.

“Our cost of living is actually kind of high in Boise now,” Perry said. “I just don’t know if young families are moving here (as fast).”

The median price of a home in Ada County increased 165% from 2013 to 2023, to $525,000 from $198,000, according to the Intermountain Multiple Listing Service. In Canyon County, the price increased 220% to $400,000 from $125,000.

Meanwhile, the median household income in Ada County increased 51% from 2012 to 2022, to $83,881 from $55,499, according to Census data. In Canyon County, the median family income increased 60%, to $68,473 from $42,691.

Focused Treasure Valley growth

According to Cortney Stauffer, executive director of operations for the Nampa School District, and Nampa Superintendent Gregg Russell, a few factors played into the need to close or repurpose four schools at once.

The district lost pandemic-era federal funding and saw a decrease in state funding when the Legislature moved to an attendance-based funding model. The district also saw a shift in local development.

“We kind of hit the unlucky jackpot,” Stauffer said.

Most Nampa new-home construction is taking place in the west and northwestern portions of the city that fall within Vallivue School District, not in the Nampa district, according to Stauffer and Russell.

Russell said district officials had hoped enrollment would stay steady if the city and developers focused on building more homes within school boundaries in the southern and eastern portions of the city. But that hasn’t happened.

“For our district, we’re just not seeing as many homes,” he said.

Joey Palmer, spokesperson for Vallivue School District, said nearly 3,000 homes are planned within a 1½-mile radius of Vallivue’s Warhawk Elementary School, which is set to open in 2025.

“That is just one microcosm example of the growth we’re seeing,” Palmer said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we needed a third high school and an additional elementary school.”

Vallivue could soon overtake Nampa as Canyon County’s largest school district. The district has sometimes written to city councils to oppose new developments, saying that it cannot keep up.

“What most people don’t realize is that school districts can’t stop growth,” Palmer said. “City councils cannot deny approval of a subdivision based on feedback from a school district.”

According to Palmer, the new construction within Vallivue is attracting families with children, while older generations are moving into the older areas of Nampa and Caldwell.

“Not only do we have a lot more land that’s being developed and approved by Nampa and Caldwell city councils, but the houses are attracting a lot more family-aged parents,” Palmer said. “We’re getting a lot more of the younger families.”

Despite this, the overall population in Nampa is getting older. The data of this demographic shift is obvious, with the proportion of those in the 50-to-79 age range increasing by 8.3% while the proportion of those in the 0-to-19 range falling 8.2%.

“The majority of people coming into Canyon County are 55 or older,” Stauffer said.

“People moving in (to Nampa School District) aren’t really having kids,” Russell said. “I think that … was really kind of alarming to us.”

The Nampa families who decide to have kids are having fewer children than in previous generations, Russell said, with most parents having one or two compared with past expectations of three or four.

Russell speculated that this family shrinkage could also be an effect of sky-high home prices and inflation, which may give young families second thoughts about having more children coupled with steep mortgage payments.

“I think there’s a lot of stats that show that Gen Z-ers tend to have children later, trying to get that career established,” Russell said. “And some of that could play, I think, into the cost of living, the cost of a home and trying to get that stable before you bring children into the mix.”

What about Boise and West Ada?

In the West Ada School District — which covers Eagle, Meridian, parts of Boise and a slice of Garden City — and the Boise School District, which includes most of Garden City, the answers are similar.

According to Dan Hollar, spokesperson for Boise School District, the majority of the decrease comes from four main reasons:

-

Declining birth rates in Idaho and Ada County.

-

Rising housing prices and the lack of affordable housing.

-

Gentrification within the Boise School District.

-

An older, retired population moving into the Boise area rather than families with school-aged children.

But the Boise School District is continuing to expand its offerings.

In April, the district hosted a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the new Dallas Harris Elementary School in the Barber Valley. The district is filling out its early childhood education programs, too.

“While we do consider that continuing to further improve and expand our educational offerings may encourage families to choose the Boise School District, our ability to impact enrollment in any significant way is severely limited when compared to external socio-economic forces such as housing costs, personal family dynamics and employment factors,” Hollar wrote in an email.

While West Ada has seen a recent decrease since the COVID-19 pandemic, it has still seen significant growth over the last 10 to 20 years. Jonathan Gillen, the chief financial officer for West Ada School District, said one reason West Ada has seen an overall increase in enrollment while Boise has not could be the difference in space for new housing.

“The West Ada School District has had, and still has, land that can be developed,” Gillen said by email. “I believe that available land has led to increased home development, and thus population moving into our district thus increasing our enrollment.”

Growth of alternative, private, homeschooling

One key of the shifting trends may be in an increase in private and home schooling.

Numbers are hard to come by. The state does not require anything for home-schooled students — no standardized testing and no need to submit a withdrawal form to pull kids out of the school system.

“We literally don’t have any data to track,” Cantrell said. “There are no assessments, there is none of those other requirements that you’d see in the typical school system.”

But the Department of Education does have public-school withdrawal numbers, which skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Between the 2013-14 and 2019-20 school years, the state saw an annual average of about 7,000 students withdraw from the public school system to enter a private or non-public setting, transfer out of state or the country, home school, drop out, or leave for other unknown reasons. There were 9,100 withdrawals in 2020-21, over 10,100 in 2021-22, and over 13,600 in 2022-23.

The state has also seen an increase in other types of public schools, such as magnet, alternative or charter schools, adding 57 statewide in the 10-year period from the 2013-14 school year through 2023-24. Of those, 42 have opened since 2019-20.

Population growth fueled by older generations

The Treasure Valley was already aging, its school enrollments already lagging, when the pandemic turbocharged the trend.

Boise’s population grew by over 61,000 people between 2000 and 2023. But the Boise School District lost over 4,000 students.

Caldwell gained nearly 44,000 new residents but lost 370 students. Nampa gained just over 63,000 residents and nearly 2,000 new students over the 23 years, though its enrollment has declined nearly every school year since 2012-13.

Two major school districts, Vallivue and West Ada, bucked the trend. West Ada grew by almost 15,000 students and Vallivue by over 6,000. Their schools are packed to the brim, with district officials searching for ways to reduce crowding.

Cantrell, who attended Centennial Middle School in Nampa, said the in-migration of older people has slowed since the pandemic. But he said the new demographic reality could make passing bonds for schools more difficult, because people with school-aged children tend to vote yes on school bonds more than people with no children in the school system.

“It becomes a very passionate community issue very quickly,” Cantrell said.

Student-enrollment declines mean reduced revenue, Cantrell said, leading officials to consider if they need to consolidate bus routes, have kids walk farther or be on the bus longer, or cut programs such as languages.

“These all have very real potential impacts on our students and families,” Cantrell said.

Closing a chapter in Nampa’s history

Russell and Stauffer said it was not easy to decide that four schools needed to close.

Stauffer, who like Cantrell attended the soon-to-be-closed Centennial, visited the school with a reporter. He pointed out his first- and second-grade classrooms and a spot near the swing-set where he lost a tooth. He said there were difficult emotions as it became clear the district wouldn’t be able to keep the doors open.

“Schools,” Stauffer said, “are very personal to each one of us.”

Nampa just voted to close four schools despite city’s growth. Which ones, and why

Gov. Little’s ‘priority No. 1’ comes to fruition: Idaho funding for school facilities

Students and educators show us what it’s like when Idaho fails to fund school repairs

Idaho hasn’t assessed school buildings for 30 years. Students and educators helped us do it

Source Agencies