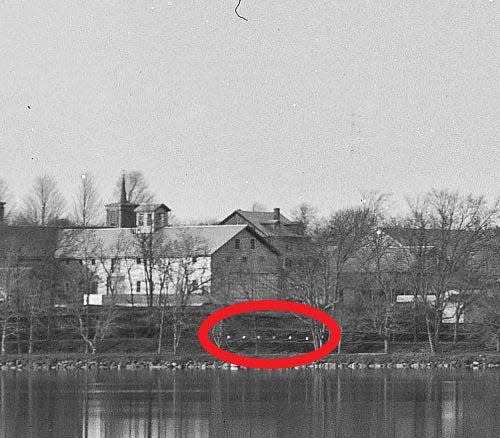

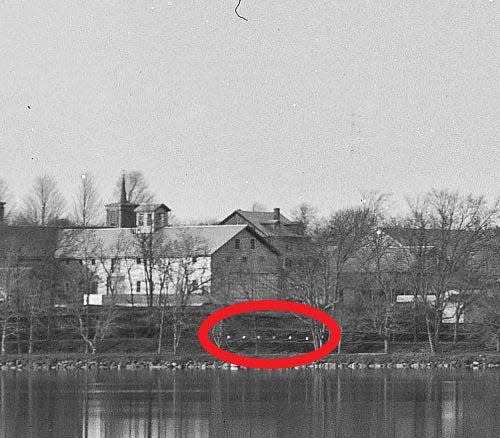

WESTBOROUGH — Beside Lake Chauncy stood Jon Maynard, who believes this is sacred ground.

Maynard’s research had led him to this small stretch of shoreline that could include the remains of boys who once lived in the first public reform school in the country.

After years of poring over historic documents and photographs, Maynard feels he’s located the cemetery that once belonged to the Lyman School for Boys, which closed in 1884. It was located on the grounds that later became the Westborough State Hospital.

Today, the former hospital site is dotted with private condo buildings and playing fields owned by the Town of Westborough. It’s on that town land near the lake where red flags were stuck in the ground to mark the spot where human remains might have been buried.

If a long-forgotten cemetery is there, Maynard wants the world to know about it.

“I want to make sure these kids are not forgotten,” he said. “If nothing is done, it will be like they never existed.”

However, Maynard may never get the chance to finish his investigation. Earlier this month he was hit with a cease-and-desist order by the Town of Westborough, demanding he stay off the property in perpetuity. If he doesn’t, he’ll be fined $300 every day that he sets foot there.

Not to be deterred, Maynard said, “I have every intention of moving forward.”

Who is Jon Maynard?

By day, the 39-year-old Chelmsford resident works as a commercial property manager. In his spare time, he hunts for historic photographs and documents.

While researching a book about the history of Westborough State Hospital, Maynard found documents that showed the reform school opened in 1848, and had its own cemetery built in 1858 where some of the school’s residents (“inmates,” according to one document Maynard shared) were buried if no family members claimed the bodies.

Maynard believes James T. Washington, a former slave born in South Carolina, could be buried on the site. Washington was sent to the school on a larceny offense and died Dec. 4, 1873, at age 16 from pulmonary consumption, according to Maynard’s research.

“When (Washington) died, there were 300 boys down here for the funeral,” he said.

Samuel Thompson is another boy who could be buried there. Thompson was sent to the school for the crime of stealing, according to Maynard, and died of consumption on June 10, 1858. Documents show other deaths were linked to typhoid fever and cerebrospinal meningitis.

Thought he was in the clear

The Westborough Conservation Commission voted 5-0 in 2019 to allow Maynard to clear overgrown brush along the lake so ground-penetrating radar could commence.

Maynard got the brush cleared, but the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the radar work was put on hold. He informed Westborough officials earlier this year that he planned to restart the project and needed to clear more brush to get the radar portion going.

That’s when his plans hit a snag.

More approvals needed

Jennifer Miller, Westborough’s conservation director, told Maynard in March that he needed additional approvals. “I agree this is an important project, but when it comes to gravesites and human remains, you are well outside my authority to grant permission for access,” reads Miller’s email.

She instructed Maynard to get permission from the state archaeologist at the Massachusetts Historical Commission and from the town’s Select Board.

Maynard was surprised Miller wanted more approvals since he had the Conservation Commission vote. Miller was not the town’s conservation director when the commission voted in 2019.

The Massachusetts Historical Commission told Maynard it can’t grant or deny approval because the cemetery isn’t located on state land. It also said a permit isn’t needed to conduct ground-penetrating radar, because it’s classified by the state as a nondestructive field investigation. That means there’s no digging into the ground, as the radar equipment glides over the surface.

However, the Historical Commission advised against radar because “it is not an effective and reliable method for locating and identifying archaeological deposits and features, such as unmarked graves, in New England soils.”

Instead, it suggested an experienced documentary historian should study documents and photos to gather more clues about the location and those who could be buried there. The result, the letter noted, could be an online memorial to the people likely interred on the site.

The Historical Commission also mentioned the possibility of an archaeological investigation to determine the precise location of the cemetery. Graves wouldn’t be excavated, but the area could be improved with fences and plantings.

Proceeds with caution

Maynard is cautious about the state’s motives, because he believes officials will drag their feet or never investigate the site.

He said as much in an email to Miller earlier this year.

“If I just hand it over to the state too soon I have every reason to suspect they’ll kill it; abandoning a cemetery for children isn’t seen as good PR. Those kids were forgotten by their family, and society, if the state kills it then even the basic dignity of acknowledging their existence will be permanently denied.”

Maynard said that when the radar work is finished, he’d be happy to hand over his findings to the state so it can take charge of the investigation. But he believes he needs the radar findings, because without them, the state could bury the project.

‘Bone finder’ hired

Maynard organized a team of volunteers in April to clear more brush and paid a “bone finder” to do ground-penetrating radar.

Bob Perry is the bone finder. He grew up in Dorchester and owns Topographix in New Hampshire. He’s been in this line of work for 25 years, hired by a variety of clients to find unmarked graves, including police departments conducting homicide investigations.

Perry typically charges about $2,000 daily for his services but dropped his fee for Maynard, charging him $1,000 for the entire project.

“He hounded me for about two years to take the job,” said Perry with a laugh. “It’s important for (Maynard) to resolve this issue, to locate the graves.”

Perry did one radar scan earlier this month that identified two “anomalies” that identified the “probability of graves.” He planned to return this month for a second scan to compare it to the previous one for a more precise analysis. That’s in doubt because of the recent cease-and-desist order.

Perry conceded the only way to know for sure if remains are buried along Lake Chauncy is to shovel into the ground. “Unless you dig it up, you don’t know if there’s a grave or not.”

Surprised, disappointed

Miller expressed dismay that the brush clearing was done without the town’s permission.

“Surprised and disappointed” were her words in a May 9 email to Maynard, “especially when all of our phone and email conversations indicated that the proposed scope exceeded the authority of the Conservation Commission because it involved human remains.”

Miller’s email also said she was contacted by the Special Commission on State Institutions and was told not only did Maynard need permission from the special commission but also from the State Medical Examiner’s office and the state Department of Public Health.

Miller declined several interview requests for this story.

Maynard doubts the special commission has the authority to weigh in on his investigation. The commission was established in 2022 to study and report on the history of state institutions for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities or mental health conditions. The former reform school doesn’t fall in any of those categories, said Maynard.

The commission has the authority to assess and compile records of burial locations for the residents who died while in the care of the institutions. It also determines the likelihood and possible locations of unmarked graves at sites of former state institutions for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities or mental health conditions.

UMass Chan Medical School is linked to the special commission. The school’s Center for Developmental Disabilities Evaluation and Research has a contract to support the special commission’s work, including aspects of the suspected burial site along Lake Chauncy.

The special commission declined an on-the-record interview about Maynard’s investigation but issued a statement.

“Part of the charge of the Special Commission on State Institutions is to look into the locations where people who lived in institutions are buried. When there is a question of a potential unmarked burial location, the Commission emphasizes the importance of following all state laws and local ordinances and by-laws.”

The statement continued: “The Commission also emphasizes the importance of working in close coordination with state and city officials throughout the entire process to ensure research is properly conducted and that the site is fully protected, including archival and archeological details of the site and any potential remains therein.”

Cease and desist

The cease-and-desist order from the Westborough Conservation Commission stated that Maynard had violated a local wetlands protection bylaw because of vegetation removal and ground disturbance without a permit. Besides the risk of fines, he was ordered to remove all social media posts and withdraw all pending media releases related to activities at the site.

Maynard said he’s “stubborn” and won’t give up the fight to have those buried along Lake Chauncy finally recognized. He plans to attend next month’s Westborough Conservation Commission meeting to smooth out any hard feelings. It that fails, he said he’ll go public with his efforts in order to generate support for his investigation.

Conservation Commission member Gary Kessler recently notified Maynard that the commission no longer supports him and advised Maynard to share his research with the state’s special commission.

Kessler served on the commission in 2019, when it unanimously voted to support Maynard’s investigation.

‘We have to save it’

Anne Dawson is in Maynard’s corner. The retired arts historian lives in a condo on the former grounds of Westborough State Hospital, and recently strolled by as Maynard gave a tour of the possible cemetery site.

“I think we have to save it,” she said.

That’s exactly what Maynard hopes to do. He’s already paid Perry $1,000 for the radar work and established a nonprofit to erect a permanent memorial on the site to remember the boys who could be buried there.

“These kids were forgotten and not valued when they died. Nobody picked them up. There was no family to get them,” said Maynard. “I’m going to take any route I can to continue. Even if it takes five, 10 years, I’m still going to try to figure something out.”

Contact Henry Schwan at [email protected]. Follow him on X: @henrytelegram.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Westborough, history buff at odds over possible long-lost burial site

Source Agencies