The researchers who raised two ancient dugout canoes submerged in Madison’s Lake Mendota announced Thursday they had discovered fragments or chunks of at least eight more canoes in the lake, an astonishing finding that promised to shed light on millennia of Native history in Wisconsin.

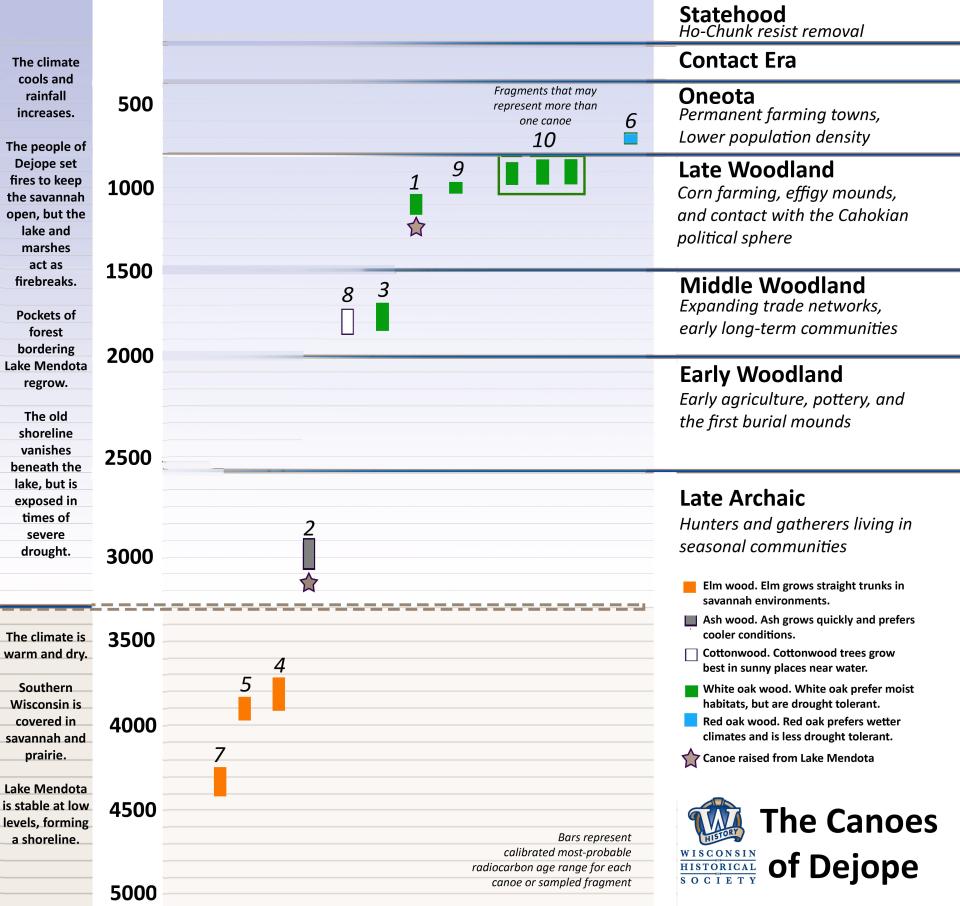

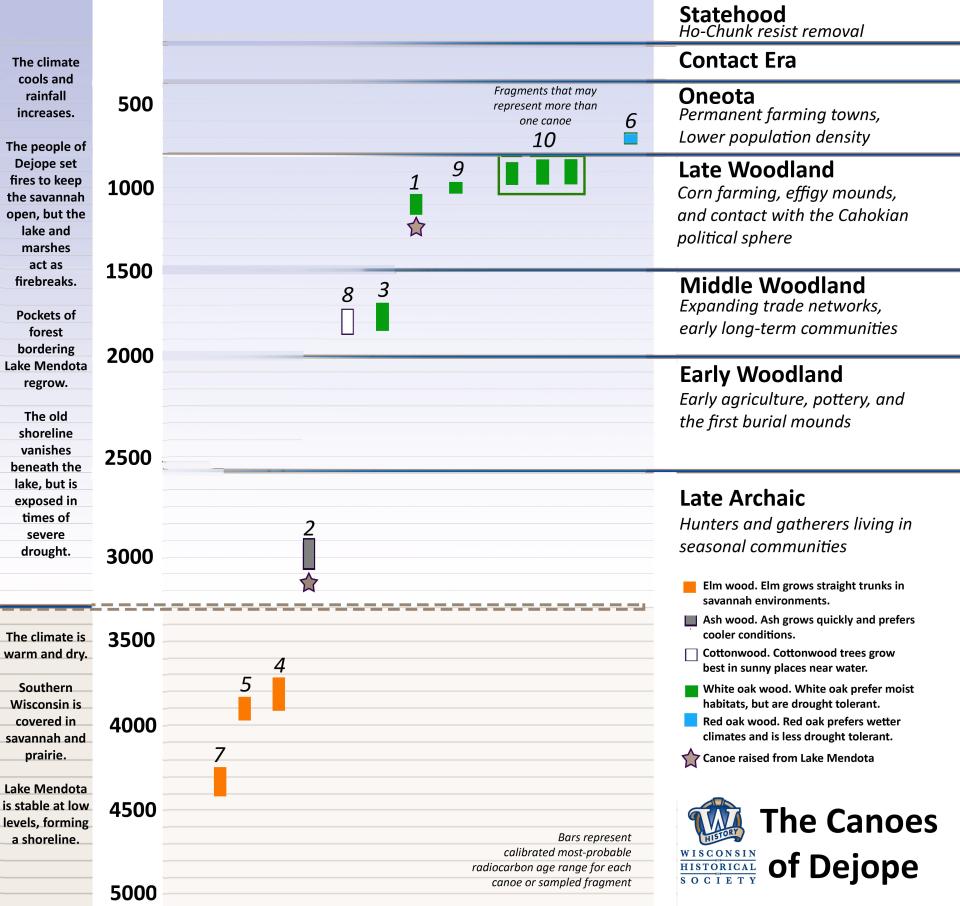

The oldest is from approximately 4,500 years ago, the oldest ever discovered in the Great Lakes region. The prior two canoes, lifted from the lake in 2021 and 2022, were 1,200 years old and 3,000 years old. The latter was previously touted as the oldest in the region.

The canoes are buried along what archaeologists believe was an ancient shoreline where people stored their canoes. The discoveries also lend credence to their theory that artifacts of an entire flooded village could lie at the bottom of the lake.

Maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen of the Wisconsin Historical Society discovered the first canoe accidentally while scuba diving. When she found the second, researchers began to suspect more canoes could be buried. Divers discovered a third canoe resting beneath the second one, state archaeologist Amy Rosebrough said.

Researchers began looking more closely; divers scanned the bottom of the lake frequently.

“It was becoming clear that we weren’t just looking at one canoe that had sunk, or two canoes — that we had an assemblage, and they might not all be the same,” Rosebrough said.

In fact, it was an entire archaeological site that is offering new insights into ancient people’s lives, especially from the oldest canoes, dated to the Late Archaic period.

“We had guessed that people were traveling by dugout throughout this period, but this is absolute proof of it,” she said.

The 10 canoes may actually be 11. Carbon dating tests offer a margin of error for the age of an artifact, and three fragments found near each other, all made of white oak, returned similar results. They could be part of one canoe or from two canoes from the same time period, Rosebrough said.

Researchers are awaiting further analysis of wood fragments to determine a final count.

Carbon dating shows a huge range in time between the other canoes. The oldest, made of elm, dates to 2500 B.C. The most recent, of red oak, dates to A.D. 1250, which is a little less than 800 years ago.

Archaeologists believe that communities would have deliberately sunk their canoes in shallow water just offshore in the fall to preserve them through the winter, returning to them in spring. They were likely buried deeper over time as the shoreline was changed by drought and floods.

The canoes span millennia of human progress and give clues to shifts in the environment. The four oldest canoes — the ones from the Late Archaic period — were used when nomadic hunter-gatherers lived in seasonal communities and southern Wisconsin was covered in savannah and prairie. The oldest canoe being made of elm aligns with the prairie ecosystem of the time, Rosebrough said.

Rosebrough put the oldest canoe in striking context: “You are 2,000 years before farming. There’s no gardening; it’s 2,000 years in the future. They’re 2,000 years before the first burial mound is built.”

Two are from the Middle Woodland period. Early farming communities, pottery and burial mounds had already been established, and trade networks were expanding. Some communities were staying in the area long-term. Pockets of forest began to regrow after periods of severe drought. Canoes made of oak signify a closed-canopy forest.

Three — possibly four — canoes are from the Late Woodland period, when corn farming and effigy mounds were prevalent. The most recent, from the Oneota period, is marked by the establishment of permanent farming towns.

Life then was markedly different from 2500 B.C., but people were canoeing on the same lake in much the same way they had been, Rosebrough said.

People who lived on the shores are Ho-Chunk predecessors

The people who lived along the shores of Lake Mendota are the predecessors of the Ho-Chunk Nation. Researchers with the Historical Society have worked closely with Indigenous leaders throughout the process.

While archaeologists did remove the first two canoes from the lake in 2021 and 2022, they decided with tribal leaders not to remove any of the newly discovered eight or nine canoes from the lake.

“If we wanted to raise the larger sections that are remaining on the lake bottom, we couldn’t,” Rosebrough said. “They’re best left where they are. They’re too fragile to bring up. And at this point, the question is why would we? We can study them just as well underwater.”

When ice covered the lake and they could walk on it, Bill Quackenbush and Larry Plucinski, tribal historic preservation officers for the Ho-Chunk Nation and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, used ground penetrating radar, a non-invasive technology to scan the lakebed. Results from that survey are pending. Another non-invasive study using a sonar boat from the Iowa state archaeology office is expected later this year.

“Seeing these canoes with one’s own eyes is a powerful experience, and they serve as a physical representation of what we know from extensive oral traditions that Native scholars have passed down over generations,” Quackenbush said in a statement. “We are excited to learn all we can from this site using the technology and tools available to us, and to continue to share the enduring stories and ingenuity of our ancestors.”

Why so many canoe discoveries all of a sudden? Rosebrough credits Thomsen’s expertise in spotting the canoes. But another answer could be that wake-surfing boats create strong currents that kick up sediment on the lakebed. Several of the canoe discoveries occurred in an area where boats take tight turns, Rosebrough said.

Meanwhile, the two canoes that divers pulled from the lake in 2021 and 2022 are continuing their years-long bath in a vat of chemicals meant to replace the water in the cells of the wood with a kind of preservative. That process is expected to be completed in 2026.

Then the canoes will go to Texas A&M University, where they will be freeze-dried to prepare for display. They are expected to be part of an exhibit at the Wisconsin History Center, a museum slated to open in 2027.

Rosebrough hopes diving expeditions and surveys will uncover more indications of the flooded village: copper fish hooks, or rock fragments from an ancient cooking technique.

Already, sharing the story of the canoes has done a lot to draw people into a closer connection with their history, Rosebrough said.

“If I show somebody a spearpoint that’s 5,000 years old, it doesn’t really seem to sink in because this isn’t something people have experience with today,” Rosebrough said.

“But when you point at a canoe, people go, ‘Oh, I recognize that.’ And then they recognize themselves in that. And then they see the people that go along with that canoe, and they can visualize the life and the deep history here,” she said.

More: Wisconsin’s past is on display at the state’s 12 historic sites

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Researchers find at least 8 ancient Native canoes in Lake Mendota

Source Agencies