Roughly around the time of the Han Dynasty and just prior to the beginning of the Roman Empire, a tree began growing at an elevation of roughly 7,000 feet in what became known as the southern Sierra Nevada.

It’s not the tallest or oldest tree in the world today, but it’s the largest when measured by volume, at 52,000 cubic feet.

The one-time sapling is believed to be about 2,200 years old and appears to be holding up well for a 275-foot-tall, 2.7-million-pound old-timer. But a few dozen of its neighbors have taken ill and died in recent years under threat from drought and bark beetle infestations, so on Tuesday the giant sequoia known as the General Sherman tree got a checkup.

A team of tree doctors from the Ancient Forest Society rigged ropes and pulleys so they could scale the cinnamon-barked skyscraper and search for signs of trouble. Anthony Ambrose, the group’s co-founder and director, explained what the trees are up against:

“Less snow is arriving, it’s melting earlier, so there’s less water available and [these trees] need an enormous amount of water. A tree like the General Sherman can use maybe 800 to 1,000 gallons of water in a single day,” Ambrose said.

“Giant sequoias are typically thought of as being very resistant to pests and pathogens. … And now … the one-two punch of fire and drought is actually making them vulnerable to beetle attack, when previously they were able to fight them off.”

A depressing thought, no doubt, especially given the role humans have played in the declining state of the planet’s health.

But it’s impossible to stand in the center of a magnificent grove of giant trees that are thousands of years old and experience only darkness, especially on a day when morning light slices through the verdant canopy near the summit of Sequoia National Park. I was reminded of John Steinbeck’s description of the sequoias’ Northern California cousins, the coast redwoods:

“The redwoods, once seen, leave a mark or create a vision that stays with you always,” Steinbeck wrote in ‘Travels With Charley.’ “From them comes silence and awe. … They are ambassadors from another time.”

Human time, in fact, is transformed by the enduring wonder of these treasures, and 70 doesn’t seem so old.

“I feel like I’m 21 again,” said 65-year-old Sheree Keohen of Huntington Beach, who was visiting the park with her husband Mike, 69.

“We could be fighting like cats and dogs, but once you hit the national park, forget it,” said Sheree. “You just forget any bills you have. Whatever it might be, you don’t think about it once you hit this beautiful scenery.”

“This is the thing you’ll remember when you die, and who knows, it might be tomorrow,” said Mike. “I can’t remember the years the Lakers won the championship, but I can remember going to see the redwoods.”

Larry Holland, 77, of St. Louis, was visiting the park with his family and had the same feeling about the magic of the spectacle before him. There’s an arrogance to our sense of importance and an illusion of control over our own destiny, he said, but we’re here and gone in a flash, preceded and survived by these gods of longevity.

“It makes you feel how small you really are,” said Holland.

Wendy Baxter, tree canopy ecologist and co-founder of the Ancient Forest Society, was about to climb the General Sherman and conduct the health check, but she took a moment to reflect on the majesty of her subjects.

“I’m inspired by their resilience — just the fact that this organism has been growing here in the same location for more than 2,000 years is incredibly humbling,” Baxter said. “And I think they provide an example for all of us on how, if you live your life within your means, if you live well and if you have the resources you need, you can be healthy and live to a good long old age.”

The trees have been pretty good stewards of the planet, providing free lodging to spotted owls, pacific fishers, flying squirrels and a host of other tenants while nurturing the ground beneath them and spawning new life.

We, on the other hand, haven’t been the greatest custodians, especially in the last couple of hundred years as changes in an increasingly energy-dependent world have made the great trees less resilient, said Baxter.

“We’ve recorded 40 large Sequoia deaths” in just a few years, said Christy Brigham, chief of resources management and science for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. The trees’ “relationship with the landscape” is changing, she said, as a tiny beetle conspires with climate change to bring down the giant ambassadors.

“We have never before seen beetles able to kill an entire large, mature sequoia,” Brigham said. “That is our concern here today.”

That, along with the drought-deluge cycle that has become the norm, with wildfires that have obliterated millions of trees, and ozone levels that foul even the national parks we’ve long escaped to for a breath of fresh air. A recent report by the National Parks Conservation Association found that 97% of the nation’s national parks suffer from ozone pollution, with Sequoia and Kings Canyon topping the list.

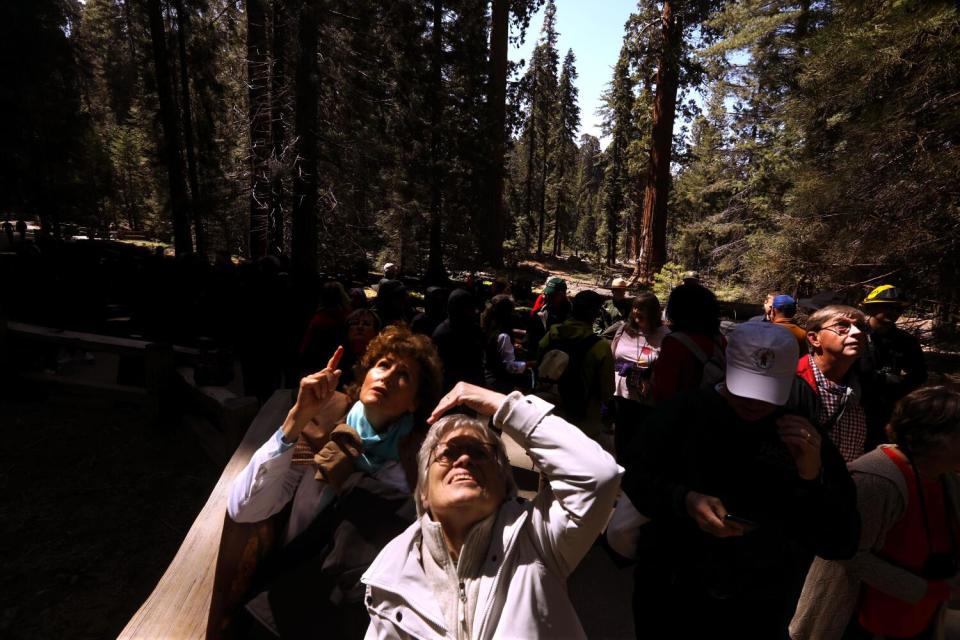

The popularity of the forest is part of the problem. Visitors flock here from around the world to stand before trees that count their age in centuries, rooted in the soil of a spinning orb that’s flying through space. The visitors speak different languages and bring different life experiences and political views to this altar of natural wonder, where they gaze up and fall silent, united in reverence. It’s inspiring to see that for all our differences, what we cherish can be a unifying force.

“When I was younger, I would find solace … and resilience in nature. You see … the renewal that takes place, and it’s just been a very calming part of my life,” said Clay Jordan, who knew early on what he wanted to do when he grew up, and now serves, at 62, as superintendent of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

For Jordan, the sequoias still are symbols of stability, serenity and perseverance. But he told me he no longer takes them for granted and knows we can all play a role in preserving them, for his grandchildren and for our own.

“I may even appreciate these trees more,” Jordan said, “because I now recognize a vulnerability … that has not existed for the last couple of thousand years.”

The scientists from Ancient Forest Society, along with other members of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, are on the case, using drones, satellite imagery and tree-climbing inspections to greater understand the vulnerability and come up with strategies to save the trees.

When the tree doctors had completed the General Sherman’s physical exam, they scaled back down to earth to share the results with park officials, forest service representatives and other interested parties, including the Save the Redwoods League

“I have good news to report,” said Ambrose.

Despite evidence of “attempted entry holes” in branches throughout the crown of the tree, the beetles “don’t seem to have been very successful,” as they have been in foraging on nearby sequoias.

The General Sherman, said Ambrose, is valiantly holding forth, defying the ravages of time. The tree “seems to be very vigorous, the foliage is very healthy, and it looks really good.”

Twenty-two hundred years old and counting.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Source Agencies