Born in the city and first living in a home on Porter and Trumbull, Ray Moncivais lived in different spots in Corktown, got married and later settled into a home down the road from Michigan Central Station, the neighborhood’s latest dazzling development that has shaped Corktown and Moncivais’ life.

The 66-year-old son of Mexican immigrants moved to Corktown with his family when his father got a job with Ford Motor Co. in the 1950s. Moncivais briefly moved back to Mexico after his father lost his job, quickly made his way back to Detroit during his childhood and later built a family of his own in Corktown, Detroit’s oldest neighborhood, which he described as being filled in his youth with working-class families of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Irish and Maltese residents.

Moncivais does tile work for various businesses, some of which are in the neighborhood, then spends his days walking his dog, stopping at Nemo’s for drinks with friends or devoting time with family.

Long before Michigan Central Station closed in 1988, he and his friends would run over to the depot to watch shoeshiners, barbers and the parade of vehicles along Vernor Highway. They would stop at the candy shop inside and simply gaze at the station’s glamour. But the landscape changed.

‘It was just a freakin’ eyesore’

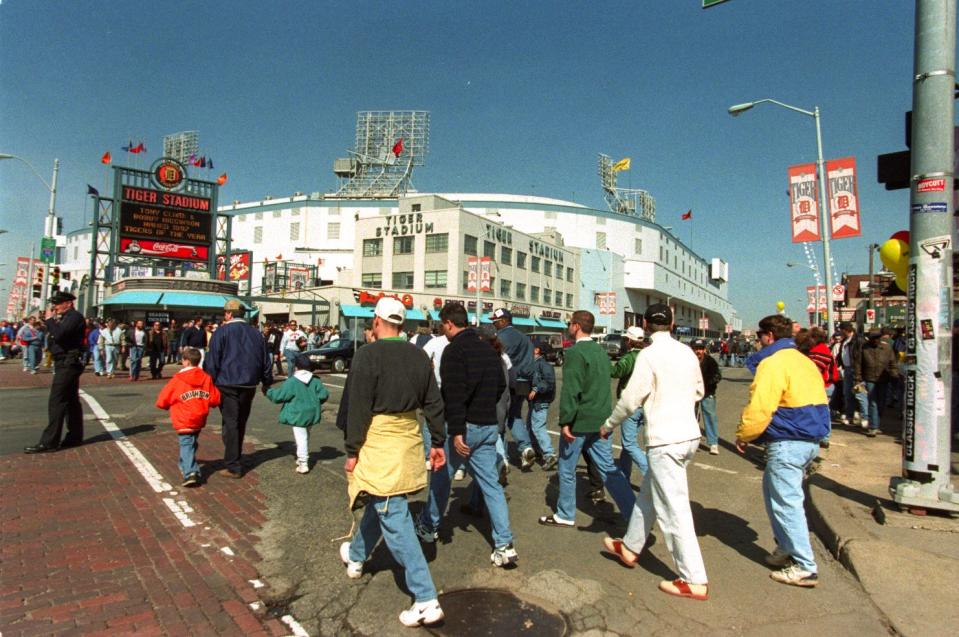

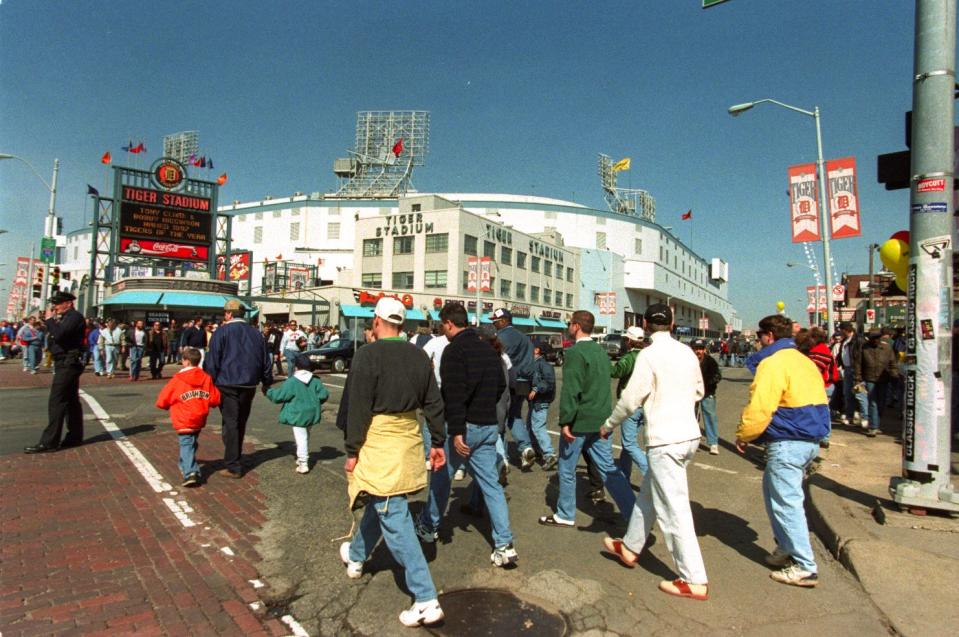

“It’s all we had,” Moncivais said. “We all played in the streets, playing baseball, football, whatever we could get our hands on. We all went to (Most) Holy Trinity (Church) … Tiger Stadium was there. There were a lot of empty lots where they parked cars for the ballgames.”

Once the train station shuttered and the Moroun family took over, it sat vacant for many years, leaving the area to dwindle, he said.

“It became desolate,” Moncivais said. “You raise a family, you take your kids to school and have to drive by that empty building. It was just a freakin’ eyesore. They wouldn’t do anything with it. They were dumping in the back, windows were being broken, they put a fence around it, but people were still getting in.”

Mayor Mike Duggan prioritized window restorations to get the building, which was once up for demolition, reoccupied. The mayor told Matthew Moroun, whose family owned the station, that their relationship would be defined by whether the Ambassador Bridge owner installed new windows.

“That became an international symbol of Detroit’s bankruptcy, and if they demolished it, it would’ve been another sad factor,” Duggan said. “I absolutely believed if they put windows in that station, people would see the beauty and start thinking of it as an opportunity and not as blight. When he did that, the buzz took off, but by then, you already had the housing being built around the old baseball field. It wasn’t that anything wasn’t going on.”

Tiger Stadium, closed in 1999, wasn’t demolished for 10 years, with the field standing unkempt for another eight years before redevelopment as a youth sports, housing and retail project.

Ford and Duggan administration ‘joined at the hip’

In early talks with Bill Ford, Duggan told the Ford executive the talent the company was seeking wants to live in Detroit.

Ford agreed, Duggan said, and a few months later, he called the mayor to say he secured the train station, a move that Duggan called “utterly brilliant.”

“I was embarrassed I’d never thought of it. But then he started to talk about building out a campus and taking the old Book Depository, and creating a place where people who weren’t Ford employees who could do startups, the vision he articulated to create a center that would design the vehicles in the future was just amazing. I bought in from day one, and our strategies have been joined at the hip from from that day forward.” Duggan said.

As soon as Ford committed to taking on the massive effort to acquire and restore the building, new apartment buildings went up and Corktown began filling with residents. Rental rates and property values increased, pressuring Duggan to track how other cities handled gentrification pushing out lower-income residents.

“We said, ‘All right, we’re going to define this neighborhood in a way that no city has done.’ And we went after the biggest grant HUD can give up for affordable housing, it’s called a Choice (Neighborhoods) grant of $30 million. Detroit was one of the few major cities in America and never (had) even been awarded one,” Duggan said.

The grant allowed the city to build 500 affordable housing units in Corktown. Despite ample development, Moncivais doesn’t see it as gentrification.

“I don’t like that term,” Moncivais said, adding that as long as residents are decent humans who take care of and improve their neighborhood, he’s happy.

“I don’t mind the neighbors now. People are moving in now at a fast rate. I see people walking around with a baby carriage … it wouldn’t be so bad if they acknowledged you, if they say, ‘Hello.’ You see people running and walking, and say hello, they may nod their head. They won’t acknowledge you. Their headphones are on, they want to live in their own little world. Back then, we used to go outside, go across the street and sit on the porch,” Moncivais said.

Old Tiger Stadium paved Corktown’s future

The neighborhood was once defined by the old Tiger Stadium. About 80 days a year were dedicated to baseball, filling streets with cars, people and at times, unwelcome behaviors, Duggan said, adding that for the rest of the year, nothing much was going on in the area.

When the Tigers moved to Comerica Park, about a mile and a half northeast in the core downtown, fears loomed across the neighborhood regarding Corktown’s future. Residents believed the neighborhood would fall out. But Duggan, whose grandmother used to tell him how much the stadium meant to the neighborhood and who often went to games with his siblings, said the opposite happened.

“It really was, ultimately, the moving of Tiger Stadium that paved the way for the Corktown that we see today … it’s one of the most vibrant neighborhoods in the city,” Duggan said, citing businesses including Slows Bar BQ, Mercury Bar and housing on the old Checker Cab site reinvigorating the community year-round. “That was all nibbling at the edges until you got to use it for the train station, which has been, for almost 100 years, at the center of the neighborhood.”

“I get more phone calls from national planning groups about Corktown than any other neighborhood in the city,” Duggan said. He attends various national conferences each year and said he often hears questions about how Ford and other developers managed to build out the area, all while the city is able to build affordable housing in a rapidly evolving neighborhood

Longtime Corktown business owners have grown to become accustomed to change, with some surviving the closure of Tiger Stadium in 1999, Detroit’s bankruptcy in 2013 and later, a global pandemic that shut down businesses.

A cornhole tournament shows neighborhood growth

Even as businesses left the neighborhood over the last several decades, Tim Springstead, co-owner of Nemo’s and Ottava Via, and a partner at Mercury Burger Bar, said Corktown was still a great neighborhood.

Springstead’s parents and oldest brother opened Nemo’s, which moved to its current location on Michigan Avenue in 1965, nearly 60 years ago.

Ryan Cooley, owner of O’Connor Real Estate and Development and a Corktown resident, said the neighborhood has a nice mix of longer-term residents and those newer to the neighborhood. Cooley, who moved to Corktown in 2005, used to put on an annual cornhole tournament in front of the train station. When he first held the event about 15 years ago, about 30 people showed up. Five years later, the event grew to about 200 people.

That DIY spirit that made events like that possible isn’t something Cooley envisioned doing in the last few years though as the neighborhood has changed following the announcement that Ford purchased Michigan Central Station in 2018.

“It just looks like such a different neighborhood,” he said. “The first decade we were there, there were some little businesses opening up, some people moving in here and there, but there wasn’t really any new construction. It’s always kind of felt the same the whole time.”

Until now.

“This whole thing is just gone into someplace that I wouldn’t have dreamt I’d ever, ever seen in my lifetime,” Springstead said. “It’s just Corktown on steroids.”

The ‘front porch’ of downtown Detroit

Corktown was changing long before Ford announced it was buying Michigan Central Station. The arrival of Slows Bar BQ, which was founded by Cooley’s brother Phil and opened in 2005, was a turning point for many of the business owners the Detroit Free Press talked with.

A meal at Slows with some friends is what led Bob Roberts, co-owner of McShane’s Irish Pub on Michigan Avenue, to open the bar and restaurant in Corktown. Before that meal, opening a restaurant in the city of Detroit wasn’t even on Roberts’ radar. But when Roberts missed his turn after dining at Slows and happened upon a building with a for sale sign out front, something clicked: He wanted to open McShane’s in Corktown.

“Friends thought we were crazy to open there,” said Roberts, who would eventually become the president of the Corktown Business Association. Roberts loved the building and the Corktown neighborhood, which he described as having a little bit of everything, from historic homes to retail and restaurants. He appreciated that “everybody was so friendly and so welcoming.”

Dennis Fulton, co-owner of Mercury Burger Bar, which opened in 2012, also liked the neighborhood and saw potential in Corktown.

“I always called it the front porch of downtown,” Fulton said. “To get to downtown, you have to enter through the front porch, and that was us. Midtown was getting built up and being saturated. Downtown was turning itself around. The next logical expansion would have been Corktown.”

Rachel Bush, a newer Corktown resident who bikes across the city, wanted to live in a walkable neighborhood with historic charm full of old buildings, adding that the momentum of the train station’s launch factored into her and her partner’s decision to move in. Despite the restaurant scene and amenities the neighborhood has to offer, she fears displacement may be a possibility for residents.

“I think prices have already gone up just around the buzz. The fact that people are excited about what this could mean for Corktown, they’re profiting off of the speculation,” Bush said. “It’s very expensive to live here. I think they should be building more housing just to make it broadly more affordable for people. But you really do pay a premium to live in Corktown. … if you’re displacing the people that make Corktown feel like the rich place it is, then it will no longer feel like Corktown.”

Change is ‘on our doorstep’

Erin Gavle opened Eldorado General Store in 2014.

Gavle was working in advertising in New York and wanted to move back to Detroit and open a store to offer an experience for people to interact with so they could say nice things about Detroit, instead of just suggesting people say nice things.

When she visited Astro Coffee in Corktown, which is now closed, she said she “could really tell people in the neighborhood knew each other. This really felt like a community I wanted to be a part of.”

She took a risk, and opened a store, which offers vintage goods and jewelry. When she heard Ford was buying the train station in 2018, she understood how huge that was and that the excitement surrounding the train station’s reopening will bring more people to visit Detroit.

Gavle isn’t entirely sure what this means for her, her business and Corktown more broadly.

“How am I going to provide for my community?” she thought. “How am I going to make sure that every person of any economic status can still participate? We’re super inclusive, so how am I going to be able to grow along with our neighborhood?”

Nearly six years after Ford announced it was buying the train station, questions remain about how it will be utilized on a daily basis.

“How is this really affecting us every single day, hopefully, in a positive way?” she said. “But it’s hard, and hard because we’ve all been patiently waiting since the announcement for these changes to happen. And I feel like it’s on our doorstep now.”

Bush, the newer resident, also wonders how the train station will serve as a “third space” for residents and whether they will be able to access any amenities within. Her fears also lie in whether those working in the building will invest in local businesses nearby.

“They may or may not patronize the businesses in Corktown. This entire catalytic redevelopment may not have the impact that everyone has thought it’s going to have. And how will the community cope with that disappointment? People could just disappear into that building and leave every day and not patronize the businesses, not connect with the community in any way, or spend their dollars,” Bush said.

Expectations for North Corktown

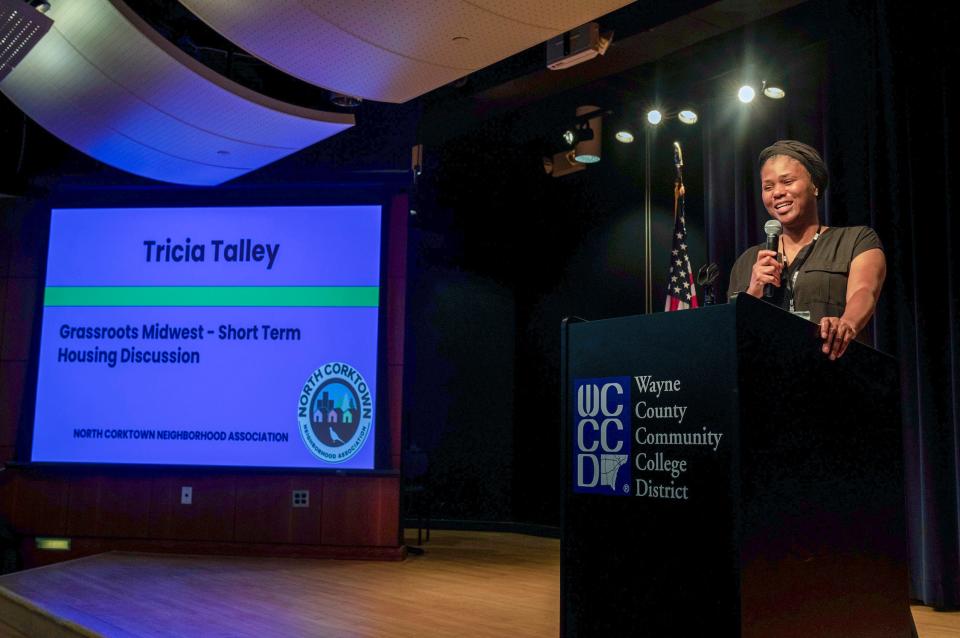

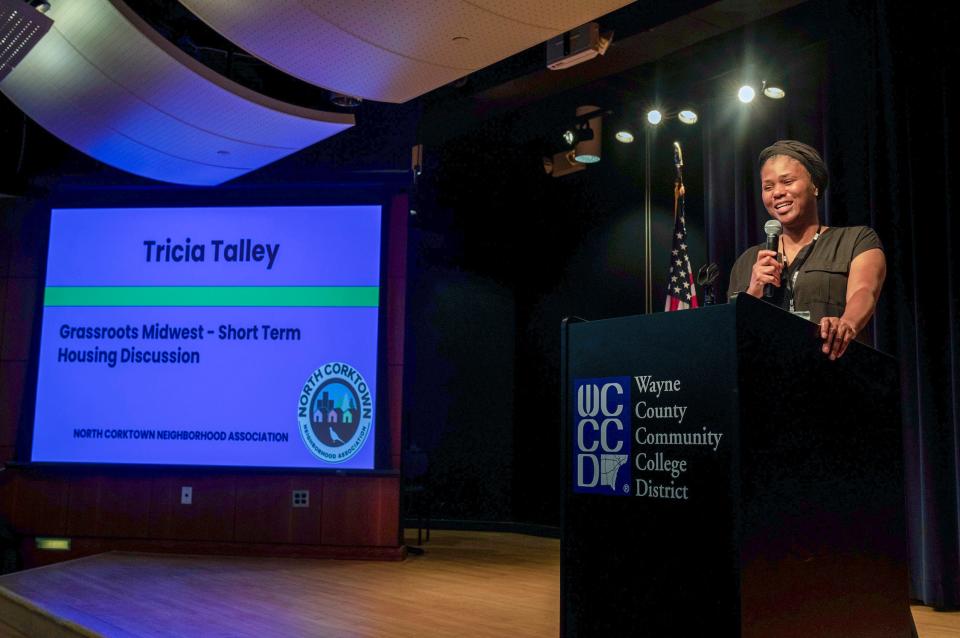

The growing development doesn’t only affect Corktown residents. North Corktown’s Tricia Talley, executive director of North Corktown Neighborhood Association, moved there in 1998 when it was full of blight, she said.

“It was not my intention is to stay as long as I have here,” Talley said. “I realized how close it was, its proximity to downtown, and I really did enjoy being really close to downtown.”

There was not, nor is there currently much density, she said, but since moving in, 90% of the blight has been removed. Talley expects neighborhood density to grow as Michigan Central Station drives more activity and aids her push for more equitable mixed income housing options in North Corktown.

“Detroit is very unique. Unlike other urban areas, we have lots of land,” Talley said. “With the removal of all of the blight, I think this is a chance for Detroit to re-create housing for residents that are interested in coming back to the city. There are a lot of people who grew up here in Detroit and they are really interested in returning to the city. But there is little development to return to and the development that is here, it’s way out of reach for a lot of residents in the city and residents that are interested in returning.”

Talley hopes Corktown’s growth involves inclusivity that’s within reach of everyone. Urban planning can result in dismissing resident engagement, she said. However, the city has been intentional with engaging the community throughout Corktown’s framework plan, Talley added.

“Besides not having any density, we don’t have any amenities. There is no grocery store, it’s just not a walkable neighborhood,” Talley said of North Corktown — though Corktown itself also lacks a grocer.

Will McDowell expects to see more people moving into his neighborhood. The 10-year North Corktown resident said many people have a misconception that the neighborhood is unsafe. However, growth through public gathering spaces, parks and other amenities were the main priorities for residents at block club meetings, not safety concerns.

“It’s the same aspect of all these other downtown neighborhoods but it’s basically under the radar, aka, it’s more affordable. But it’s just as valuable in my eyes,” McDowell said. “I wanted a real community. I didn’t want a place where most people were renting, or most people were planning on being there temporarily.”

Michigan Central has been a good community partner to North Corktown residents, McDowell said, adding that there are reasons to believe Ford will continue being a part of the support through time, resources or funding.

“You can tell it’s more than the bare minimum. We have Saturday meetings, they have someone representing themselves there. That’s not in the rulebook that they have to do that,” McDowell said.

Although he supports the major developments in Corktown, he wants stakeholders to ensure they’re inclusive of neighboring communities and that projects actually improve the quality of the neighborhood. Knocking down the Tiger Stadium brought in new housing, along with the train station expanding residences into nearby neighborhoods.

“There’s always been a culture of the down-to-earth, passionate people in North Corktown, and as we grow, we want to welcome people into that culture and be intentional about that, and we need the support of all the stakeholders in the region, including Michigan Central. So far, we feel like we’ve been heading in the right direction,” McDowell said.

The neighborhood is already changing

To prepare for the potential changes that will come with the opening of the train station, Fulton is planning to expand Mercury Burger Bar’s hours and open for breakfast.

Roberts said he already hired five additional employees for the NFL draft that was held in Detroit in April, so he feels prepared with 37 employees for the train station to open and whatever additional traffic that will bring.

Said Gavle, “We’re going through this huge growth, and growth equals change. And so I think we’re just like, kind of figuring out what that all means, together as a community, both residents and business owners.”

Fulton believes the neighborhood has already started to become saturated. He believes there’s a place for him and Mercury Burger Bar, though, no matter how it changes.

“The Mercury will be there another 10 years at least,” Fulton said. “We’re not going anywhere.”

Dana Afana is the Detroit city hall reporter for the Free Press. Contact: [email protected]. Follow her: @DanaAfana.

Contact Adrienne Roberts: [email protected]

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Corktown, Detroit’s oldest neighborhood enters new, glitzy era

Source Agencies