Barbara Plett-Usher,BBC Africa correspondent

Reuters

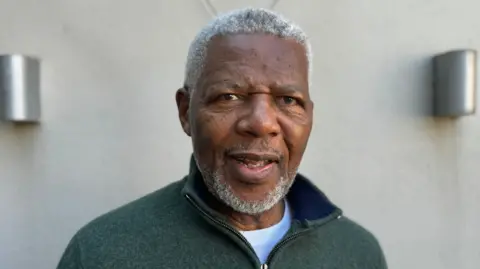

ReutersMavuso Msimang read the writing on the wall last year and now the people of South Africa have confirmed what he saw.

The veteran of the African National Congress (ANC) resigned from the party in December after 66 years, citing endemic corruption, and warning that the ANC was on the “verge of losing power”.

The party has lost the position of unrivalled political power it’s held since the end of apartheid 30 years ago, with a sharp drop in support.

As South Africans digest a pivotal moment in their history, they are looking back at what this means for the former liberation movement, and forward to what it means for the future of the country.

“I think all of us can agree it’s about time we have change,” says Lerato Setsiba, a computer science student at Johannesburg’s University of Witwatersrand.

“But I think a majority of the people at the moment, we’re quite scared… we don’t know what’s going to happen.”

The past

Mr Msimang’s house is furnished with tributes to the ANC’s iconic former leader – a life-size painting of Nelson Mandela, a coffee-table book bearing his name.

Mr Msimang served in the ANC’s armed wing uMkhonto weSizwe in the 1960s and was appointed to several government positions after the 1994 elections that brought the movement to power.

He’s now the deputy president of the ANC veterans league, which has strongly advocated for action against corruption in the party’s ranks.

“There was always a tendency to not deal with issues of accountability,” he says, but the economic mismanagement that resulted “affected people very directly”.

“When I saw those long queues [of voters] which are almost similar to what happened in 1994, I didn’t think that they were queuing to celebrate the ANC. It became very clear to me that something bad is coming.”

“I’m very disappointed,” he told me. “I don’t know how the ANC’s legacy will be retrieved. I hope this is not forever.”

Many older voters who remember the horrors of apartheid remained loyal to that “liberation legacy” – the ANC’s leading role in overthrowing white-minority rule.

They also remember its progressive social welfare policies that lifted millions of black families into the middle-class and expanded basic services such as water, electricity and welfare to millions more.

But the party began to attract people interested in power and political patronage.

Its downfall really began under former President Jacob Zuma, who resigned in disgrace amid allegations he’d allowed business associates to infiltrate government ministries. He denies the allegations.

Mr Zuma was replaced by Cyril Ramaphosa, who has been accused of not taking strong enough action to root out corruption from the party.

Nevertheless Mr Msimang, has not given up on the ANC. He was convinced by his veteran comrades to rejoin the party.

“I don’t think all is lost. There is time for the ANC to regroup,” says Mr Msimang.

“But the renewal of the ANC would take the form of making sure that elements who are really corrupt are removed from the organization. We’ve really failed to act decisively to do that… we have not heeded the pleas of the people.”

Nevertheless, Mr Msimang is worried about the absence of a strong alternative to the party: “There is this fragmentation, which is going to leave the country very unstable if this persists.”

Ed Habershon/BBC

Ed Habershon/BBCThe present

At the elections results centre near Johannesburg the numbers tick up on a dashboard tracking the vote-count.

Its giant screen towers over a hall crowded with journalists, party officials and analysts such as Susan Booysen. She found a quiet place to speak with me.

The topic is coalition politics, which South Africa has not had at the national level for two decades. Though the ANC is still by far the largest party, it will need to share power in order to continue governing.

The political landscape is tricky, and fraught with consequence because the major parties have different visions for the country.

The pro-business Democratic Alliance is not an easy fit because of its free-market agenda and its reputation as a party for the white community and other minority groups.

The next two biggest parties are on the radical left, Mr Zuma’s new uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) – a name it adopted from the ANC’s paramilitary wing – and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). They talk about seizing white-owned land and nationalizing mines and banks.

The ANC regards the EFF as “too erratic in its orientation, too in your face, and too unreasonable in its policy demands,” says Ms Booysen.

And there’s too much “bad blood” between the ANC and MK, which has said it won’t partner with the ANC as long as Mr Ramaphosa remains its leader.

Unseating Mr Ramaphosa is “the MK party’s main objective at this stage, and the ANC is collateral damage in that process as far as they are concerned,” she says.

Mr Zuma’s comeback despite presiding over a decade of rampant corruption has thrown a wildcard into the mix. He swept into the convention centre on Saturday night to make allegations of election rigging.

The outcome of what’s expected to be turbulent coalition talks could decide between two very different directions for South Africa.

Ed Habershon/BBC

Ed Habershon/BBCThe future

On the campus of Johannesburg’s Wits University, a troupe of student actors is performing a pop-up parody of the election.

People turned out in large numbers to vote here – many of them, like medical student Nobuhle Khumalo, for the first time.

She’s excited about change but doesn’t know what it means: “We’re just going to see what it looks like as it unfolds.”

We’re chatting on the grounds in front of the library with two of her friends, Mr Setsiba and music student Silka Graetz.

They hope a coalition government will bring more accountability and transparency, but are wary it might result in greater political instability and dysfunction.

“I think the increase of votes with other parties definitely creates a healthy competition,” says Ms Graetz.

“And I think with healthy competition comes better service, just an improvement in so many different fields.”

Young people, many of whom did not experience apartheid, were more willing than their parents to abandon the ANC, powered by concerns about their future.

Some 45% of South Africa’s youth are unemployed, the highest recorded rate in the world.

“When it’s campaign time you’re not speaking to issues that concern young people,” says Mr Setsiba, criticizing government budget cuts to education in recent years.

“Pour funds into universities, stimulate entrepreneurship, and make it a thriving country for new businesses!”

Ms Graetz warns that it will be important to restore investor confidence in the country in order to improve the economy.

Both she and Mr Setsiba are preparing to graduate, so launching into the job market is at the top of their minds.

Ms Graetz is acutely aware that her future will be formed in the next four or five years, the time period before the next election.

“The one question I have is: ‘How long we have to wait to see something [change]?’” she says. “I think there’s been a big attitude shift. How much longer until that’s put into action?”

It took 30 years for the ANC to be held to account for its failures. South Africa’s younger generation is not prepared to wait that long.

Source Agencies