Mike Pence could not have asked for a more welcoming audience. For nearly 30 minutes, the man who served as Donald J. Trump’s vice president was repeatedly applauded as he offered a vigorous affirmation of his support for Israel at a conference of mostly conservative Jewish leaders in midtown Manhattan.

He barely paused when his questioner, Zvika Klein, the editor in chief of The Jerusalem Post, asked Mr. Pence, an evangelical Christian, to lead the room in prayer for the Israeli hostages captured by Hamas on Oct. 7. “It would be my great honor: Let us pray,” he said.

His invocation drew applause and shouts of “Amen.”

In the seven months since he dropped out of the race for the Republican presidential nomination, in the face of inevitable defeats in the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary, Mr. Pence has been seeking out friendly audiences like this one as he embarks on a mission to resuscitate his political career. But just as importantly, he is presenting himself as the guardian of the conservative traditions of a Republican Party that he grew up with and that have since been redefined by Mr. Trump.

He has begun turning up on high-profile television interviews to criticize Mr. Trump’s position on abortion, in one example. He announced that his political advocacy group would spend $20 million this year on appearances and advertisements that promote endangered conservative positions on issues including tariffs, government spending and America’s role in the world.

Mr. Pence is the most prominent Republican in the nation to declare that he would not endorse Mr. Trump, the man who chose Mr. Pence when he was governor of Indiana and put him in the White House. And he has made clear that, at the age of 65, he is not foreclosing another bid for the presidency.

“The role I want to play is to be a champion for a broad, mainstream conservative agenda that’s defined the Republican Party since the days of Ronald Reagan,” he said in an interview before his appearance at the conference. “I see some evidence that some voices in and around our party are departing from that — I want my voice, my organization, to be an anchor to windward.”

Yet for all that, Mr. Pence is clearly out of step with the party that once embraced him. For many Trump loyalists, he is still the vice president who refused to go along with Mr. Trump to hold on to power on Jan. 6, 2021.

“Judas Pence is a dead man walking with MAGA, regardless of the 30 pieces of silver in his PAC,” said Stephen K. Bannon, a leader in Mr. Trump’s movement, referring to Mr. Pence’s advocacy group, Advancing American Freedom. (He made his remarks in a text a few hours before a federal judge ordered him to report to prison by July 1 to start serving a four-month prison term imposed on him for disobeying a subpoena from the House committee that investigated the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.)

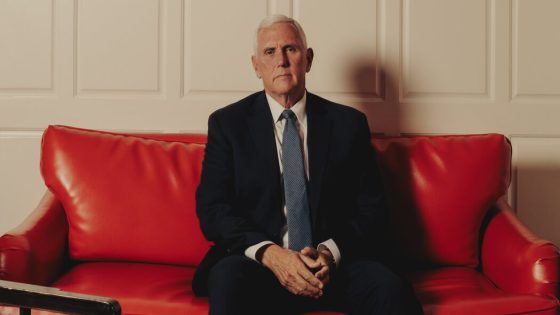

With his low-key, Midwestern presence, Mr. Pence stands in sharp contrast with the Republican Party of today, personified by Mr. Trump and, for that matter, by Mr. Bannon. In the interview, Mr. Pence, speaking softly as he settled on a couch, seemed taken aback by the suggestion that he had become an island in his own party, a Republican Robinson Crusoe standing alone as Mr. Trump remakes their party in his name.

“I hope not,” he said. “I hope I’m on a continent. I’m where I’ve always been since I joined the Republican Party.”

“When I was running for president, people would often say, ‘Mike Pence’s problem is that he’s running in a Republican Party that doesn’t exist anymore,’” Mr. Pence said. “That wasn’t my experience. Everywhere I went on the campaign trail, people, whether they were supporting the former president or supporting someone else, almost invariably would say, ‘I appreciate what you stand for.’ I’m convinced that this is still a conservative party.”

Yet the signs of his isolation are abundant. Mr. Pence said he had not spoken to Mr. Trump “for a long time.” Republicans say it is unlikely that he will be offered a prominent speaking spot when the party gathers for its convention this July in Milwaukee. A YouGov/Economist poll from March found that 52 percent of Republicans had an unfavorable view of Mr. Pence, compared with 42 percent who had a favorable view of the former vice president.

And despite the way he recalled his reception on the presidential trail, Mr. Pence never broke out of the single digits in most of the early polls, even with the advantage of being a former vice president. He was forced to drop out of the race before he even made it to Iowa.

The notion of a former vice president not supporting the president he served is so extraordinary that President Biden invoked it in a sharp-edged joke at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner this year.

By contrast, Nikki Haley, the former United Nations ambassador, and Ron DeSantis, the Florida governor, who both drew far more support in their own unsuccessful bids for the Republican presidential nomination, said they would vote for Mr. Trump. Mr. Pence said he would not vote for Mr. Biden, but would not say who he might support.

“I like Mike very much — I strongly recommended him to Trump in ’16,” said Newt Gingrich, the former Republican speaker of the House. But he said: “Mike Pence now finds himself in a party that sounds different than it used to while appealing to a constituency that is different from two years ago. And unfortunately for Mike, that tends to drive him into a corner. At his current trajectory, he is going to shrink down into the Never Trump vote.”

“There is no future in the Republican Party in being the anti-Trump,” Mr. Gingrich said.

Mr. Pence has walked a fine line as he has sought in these past months to distinguish himself — and criticize — a figure as enormously popular in the party as Mr. Trump, a former ally who is trying to muscle Mr. Pence out of the spotlight.

In the interview, Mr. Pence denounced the case against Mr. Trump that led to his convictions on 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to cover up a $130,000 hush-money payment to a porn star. “I expect his felony convictions will be overturned. This case should never have been brought.”

But at the Jerusalem Post forum, he barely talked about Mr. Trump other than to link himself to Mr. Trump’s decision, as popular in this room as the former president himself, to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Mr. Pence argued that it is Mr. Trump who has changed over these past four years, drifting away from traditional Republican positions.

“On a whole range of issues, I have seen the president running on an agenda that’s different than what we governed on,” Mr. Pence said. “I see the president moving in the direction of some of the isolationist voices in our party. Or the national debt — he never even tried to reform the entitlements that represented 85 percent of our federal spending.”

Mr. Pence has been particularly vocal in assailing Mr. Trump on abortion. While Mr. Pence and many other conservatives are pushing for a national ban on the procedure, Mr. Trump has called for leaving restrictions to the states. Mr. Pence’s position has earned him some admirers in important corners of the Republican coalition.

“He’s the steady rudder of the pro-life movement among Republican leaders,” said Marjorie Dannenfelser, the president of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, a leading group opposing abortion rights. “He doesn’t change. He has never been a person who was testing the winds.”

Ms. Dannenfelser, whose organization is supporting Mr. Trump this November, said Mr. Pence would have a well of support from abortion opponents should he decide to return to politics in a post-Trump world.

“On the other side of this coming presidential race, there will have to be a gut check,” she said. “And he would be an important and essential part of that gut check.”

Tim Chapman, a senior adviser to Mr. Pence’s advocacy group, said that the former vice president saw himself as “a keeper of the flame during a pretty tumultuous time on the right.”

“Everyone is playing the game of showing how close they are to Trump,” Mr. Chapman said. “We don’t have to pretend. Everyone knows where we are. We are liberated in ways that no other group is liberated.”

As Mr. Pence travels the country, giving speeches and interviews, raising money, presenting himself as a potential future candidate for national office — “I’ll keep you posted,” he said when asked if he would seek the White House again — his next chapter seems bleak, at least through November.

Mr. Pence is going up against the most powerful figure in the Republican Party since Ronald Reagan. As of today, there seems little room in the Trump world for a candidate like Mr. Pence.

“He’s finished,” Mr. Bannon said. “But like all career politicians he is addicted to being relevant.”

Source Agencies