The dream started with a sickly mother at an Indianapolis apartment complex known for trouble. Carl King, 25, decided early in his teens that nursing was going to be his career path.

That reality was hard to realize growing up inside a bank of east-side apartments in the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood. The complex may have changed names several times over the years, but residents know it as “Hillside.”

Within their home was an environment that fostered academia.

“I always lived in Hillside. I grew up with a single mother and two sisters, but I’ve always taken AP honors classes. My big sister was valedictorian at her school,” King said.

More: Martindale-Brightwood loses its sense of self as gentrification moves in, residents say

Outside of it was an environment known for fostering crime.

Hillside’s struggles and people trying to change it

Thom Kenneth has been a maintenance worker inside Hillside, currently named New Bridge, for a while and said he has seen it all.

“I try to do more and go beyond with the kids here. We really try to talk to them you know,” Kenneth said, “There’s no safe spaces for them to enjoy being kids.”

Despite its reputation for challenges, Martindale-Brightwood residents, organizations, churches and community leaders are actively working to redefine the Hillside narrative.

The Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood is bounded by East 30th Street on the north, Sherman Drive on the east, Massachusetts Avenue, East 21st Street on the south, and the Monon Trail to the west. The area of just under 9,500 people includes primarily Black residents according to the Martindale-Brightwood Quality of Life Plan, an annual report compiled by community stakeholders.

More than 60% live at or below the poverty line.

Gangs have played a significant role as far back as the 1980s, according to The Polis Center‘s timeline on the neighborhood.

Related: Former Indianapolis violence reduction director to lead Brightwood Community Center

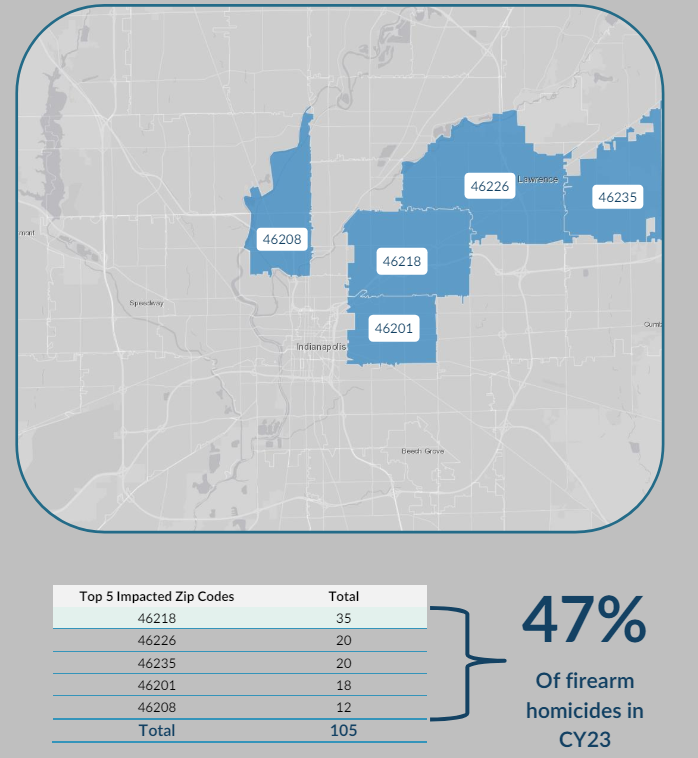

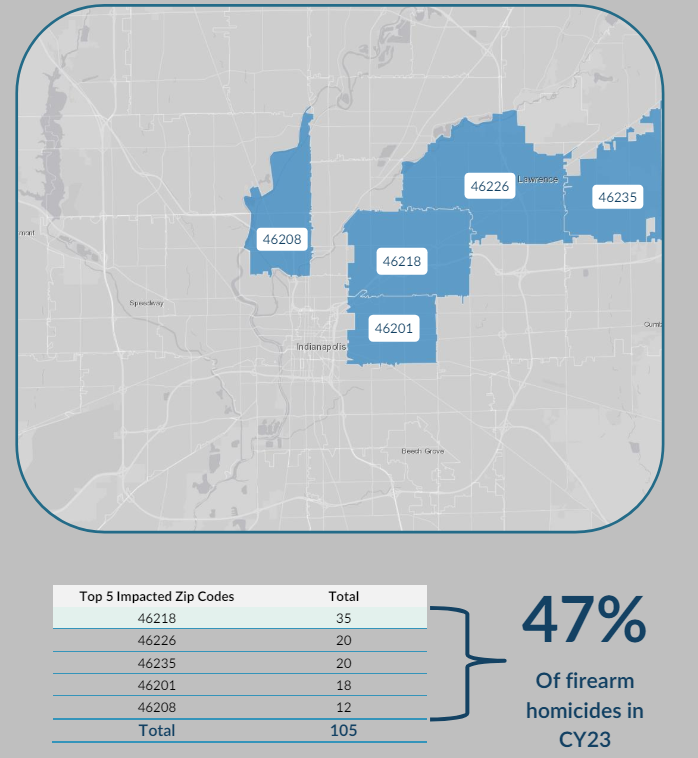

Fast forward to the present day and the annual report from the Marion County Coroner’s Office shows that the 46218 ZIP code, which is where Martindale-Brightwood is located, had the most deadly shootings in 2023.

At “Hillside” alone, there have been seven homicides in less than five years, making it one of the deadliest complexes in the city.

Shelly Corken became the new property manager four months ago. She has made safety changes for the complex including hiring an on-site security team and adding more cameras in and around the complex.

“I have no tolerance for crime to keep coming in here and keep disrupting my tenants that have been here since 1988,” Corken told news outlets in April.

More: Why Martindale Brightwood is getting $3.5 million from the city of Indianapolis

A juvenile record and a dream derailed

Hillside’s influence derailed Carl King’s nursing dreams.

“I was in 10th grade just turning 16 and I still remember it. I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. My buddies robbed someone and I’m right there with them,” King said.

He was charged with two counts of robbery resulting in bodily injury.

King spent three days in the Marion County Juvenile Detention Center, right around the corner from the apartment complex. One charge was then waived to adult court so he would spend time in the county jail before being transferred to Pendleton Correctional Facility.

“I’ve never been in trouble before. I’m still a kid,” King said.

When his public defender visited him in prison, King learned his other charge stayed in juvenile court.

While discussing his case, the lawyer asked him a question that would change the course of his detainment.

What do you want to do?

“I want to be a nurse.”

What makes you think that you could do that?

“I was in AP honors.”

That conversation, King believes, led to him being released.

He had been sentenced to seven years for the charge that was waived to adult court. Five were suspended but he spent one year in community corrections and Pendleton with the other year on house arrest.

If he got in any trouble again, he would be back in the system with an automatic sentence.

King enrolled at Arlington High School that fall where he said he maintained a 4.3 GPA.

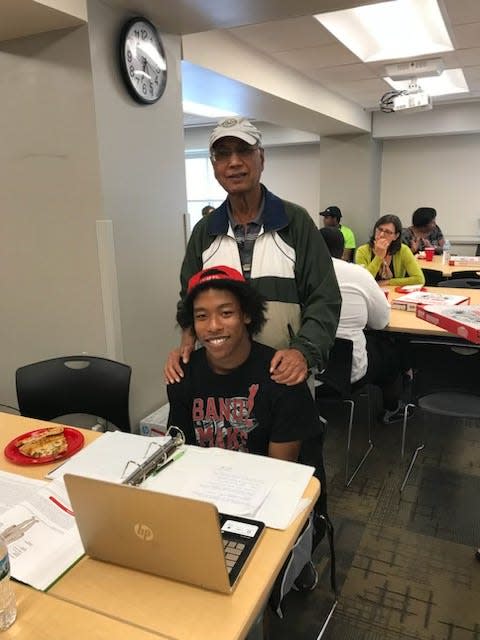

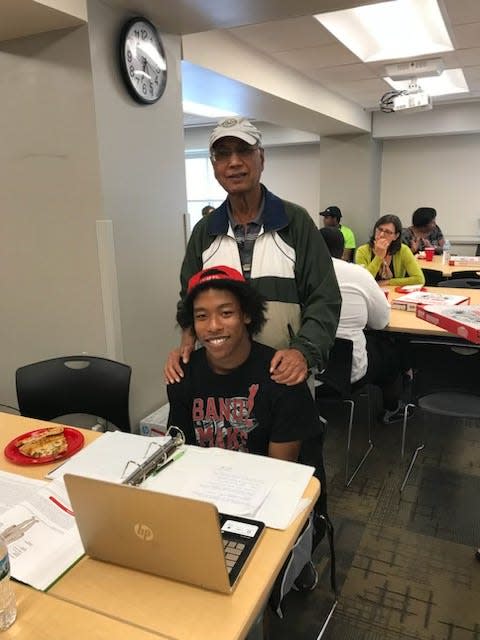

That is when he met representatives from Walker Charitable Foundation an organization established to fulfill the dream of Charles and James Walker, two African American brothers who personally knew the hardships involved in attaining higher education. The group provides scholarships to colleges and operates solely inside Indianapolis Public Schools.

“Carl King was a part of our first cohort,” Walker Foundation board member Lee C. Christie said. Christie is also a partner at Christie Farrell Lee & Bell.

King would be awarded the foundation’s scholarship to Ivy Tech Community College’s ASAP Program after writing an essay about the greatest hardship he had ever endured: Being in prison.

Christie said King was a “star student” who came with little worry from mentors about his academic future.

King graduated high school and started attending the college, which accepts students with criminal backgrounds. Everything seemed OK, until he got a summons in the mail.

His old case was back to haunt him years later.

Christie was shocked when he received a call from King’s mom that he was back in jail.

“Prosecutors were trying to waive the case to adult court, but at the time retired juvenile Judge, Marilyn Moores, was very protective of her kids. She’d say, ‘No, keep him here.’ Even still, this was in the background for all that time and was finally waived to adult court,” Christie said.

Christie, a lawyer, assembled a team to help King and served as a character witness in his case. King pleaded guilty to get out of jail and put the situation behind him.

“He had a no-bond hold, too. So, he would have been in there for a while,” Christie said.

King’s case saddened Christie because not everyone has a team of lawyers ready to jump to their defense.

“He’d have been stuck in the system otherwise,” Christie said. “He would have flunked his finals, too.”

King was released on probation and got back in the classroom, but put a pin on becoming a nurse.

“In my mind, my back is against the wall. I’m wondering how I’m going to be a nurse. I can’t get a job at all. I’m living off my college stipend and grant money,” King said.

King pulled from another Hillside childhood experience to calculate his next move.

“I’m a felon still living in Hillside in this environment,” King said. “I grew up in Hillside with no central air and I used to turn on the stove to heat up the house all the time.” He joined Ivy Tech Community College’s HVAC program.

Christie encouraged him to email the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office about getting his records expunged, but King had little hope that anyone in the judicial process would be on his side.

At the same time, King was watching his mother — the whole reason he wanted to become a nurse — deteriorate. She had been on dialysis for eight years and had three heart surgeries and a quadruple bypass. He felt hopeless.

“I tell her, ‘Stuff I did as a kid I can’t overcome it, Mama. I’m tired.’ She told me to keep sticking with it. She never gave up on me.”

His mother passed away a week before his 23rd birthday.

“We were at home. Inside this Hillside apartment. She gave me a hug and said she loved me before she passed.”

King would vent his troubles to his college counselor at Ivy Tech. He wanted to quit.

It’s going to take time, the counselor said.

“I don’t got time,” King retorted.

The next day King got an email from the district prosecutor’s office saying his cases were being expunged. He could be a nurse, after all.

Marion County Prosecutor Ryan Mears said King’s progress from being a youth in the juvenile justice system to being an adult trying to succeed was the reason his office petitioned for the court to grant expungements for his records.

“We saw that he had tremendous support and this commitment to his academics. We saw his grades. He was a young person who had really done what we want young people in the juvenile justice system to do,” Mears said.

Previously incarcerated people who have jobs and homes, Mears explained, tend to not commit crimes again. The type of expungement King received doesn’t happen often, but a judge reviewed his case and King’s commitment to personal growth to give him another chance.

King is not taking that for granted.

He earned his Licensed Practical Nurse certification in the spring and plans to enroll to become a registered nurse in the fall.

“That’s my story,” King said. “Don’t let your environment stop you.”

This article was produced for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems. Surveys collected within the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood were done via an USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s engagement grant.

Contact Jade Jackson at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @IAMJADEJACKSON

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indianapolis ex-felon defying the odds with his pursuit for nursing

Source Agencies