For the past 10 years, as each May gives way to June, Jennifer Byrum has celebrated her sobriety. Each year is a reminder of the life she left behind and the life she has now.

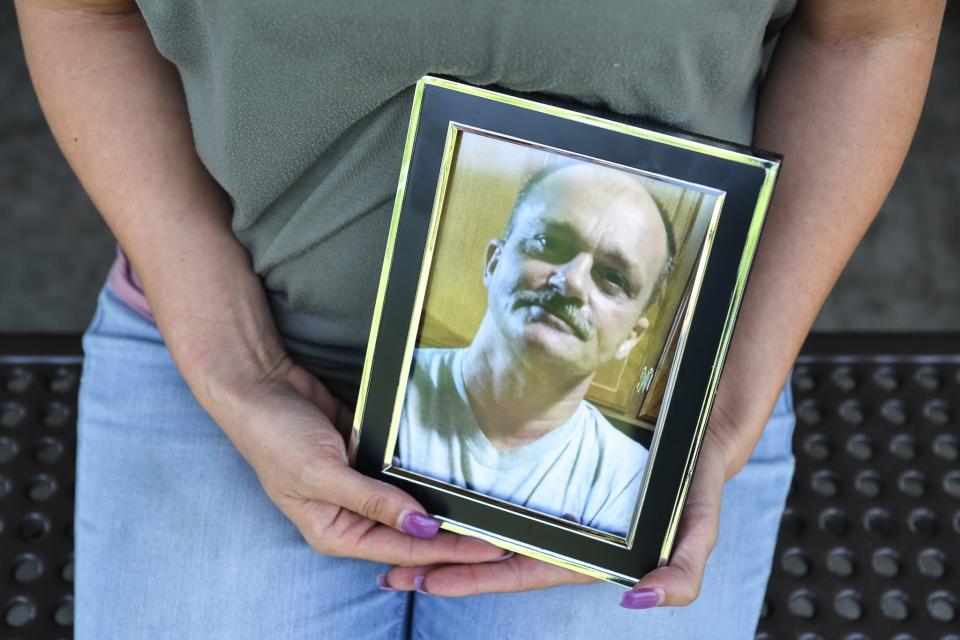

This past year has been the most difficult as she’s had to wade through shock and grief after her father died on May 26, 2023, after suffering for hours in a jail cell at the Knox County’s Roger D. Wilson Detention Facility. The medical examiner’s office ruled Ricky Lewis’ death “accidental” and “drugs/poisoning.”

Any death is enough to wreck a person, but the nature of Lewis’ death spurred Byrum to file a federal lawsuit against the Knox County Sheriff’s Office and its jailers. She’s alleging, among other things, that the sheriff’s office violated her father’s 14th Amendment rights. The constitutional protection is designed to shield a person from losing their life, liberty or property without due process.

The events that cost Lewis his life began at 4 a.m. May 26, 2023, when the 54-year-old man called police while under the influence of drugs on an unlit county road. His final hours were torturous. He was left alone for hours as he suffered a mental breakdown, ending up naked and thrashing in his own feces.

Last month, as Byrum prepared to celebrate her 11th year sober, she planned a balloon release in honor of her late father. The two dates are now forever linked.

Ricky’s problems

Lewis was an addict. His criminal record dates back to the 1980s and is 57 pages long, a wide range of mostly low-level offenses. He fought alcohol and substance abuse for decades, alienating friends and family at his worst, drawing them in with encouragement and warmth at his best. His last week alive was more of the former.

He also struggled with mental health issues likely escalated by his drug use. Specifically, he struggled with anxiety and depression, according to medical records and confirmed by his ex-wife Kim Murphy. In 2012, he tried to hang himself while in a jail cell. He later said the attempt wasn’t serious, that he was joking with a cell mate.

His depression and anxiety were deep-seated and debilitating. His parents, he told his daughter, “never said ‘I love you.'”

“I think,” Byrum said, “between the mental health and the addiction he was just trying to cover up his demons where he didn’t feel anything and he didn’t think about stuff.”

Arrest and custody

Lewis had been living with Byrum, her husband and two kids up until the week before his death when, she said, he began relapsing. Because of this, she told him to leave, and he bounced around from place to place, homeless.

Those close to him don’t know why he called the police around 4 a.m. May 25.

He told responding deputies he was trying to take his blue 1990s-model Chevrolet pickup truck to his father’s house − where he would sometimes sleep in the driveway − but they weren’t buying it.

Deputy Dennis Sosville told Lewis he was stranded outside a “known drug house” and Lewis, for his part, was incoherent at times. After searching his truck − which Lewis consented to − another deputy found a pipe. Deputies said they later found what they said was heroin in his wallet.

The encounter didn’t end well for Lewis. Deputies said he tried to resist arrest, though the body camera footage doesn’t show exactly what happened. Regardless, Lewis was taken to the ground and handcuffed.

Once in custody, video obtained by Knox News shows Lewis in various states of unrest, often refusing to cooperate with jailers and medical staff. And as the encounter extended, his treatment by jailers and medical staff worsened.

Lewis loses consciousness

Shortly after his arrest and booking, around 6:45 a.m., Lewis was in what appears to be an intake hallway surrounded by jailers and nurses, according to a six-minute body camera video obtained by Knox News. Slouched against the wall, Lewis couldn’t keep his head up as he dipped in and out of consciousness.

After unsuccessfully trying to wake him, a nurse put smelling salts under his nose, which briefly woke him before he slouched again. This was repeated.

Jailers and nurses huddled around him – there were up to nine at one point – trying to figure out what to do with Lewis.

Their general consensus, caught on the bodycam video? Lewis was faking it.

“All right, that sounds awesome. Come on man, stand up for me since you want to play games. Walk!” an unidentified jailer said. “Now, come this way since you want to act up. Just walk for me.”

Eventually, the jailer dragged Lewis up, bending his fingers back toward his wrist, and moving him to a holding cell.

He spent the next nine hours there.

The hours stretch on and on

Lewis lay on the concrete floor still in the clothes he was arrested in: blue jeans and a T-shirt. He wore no socks. He spent most of his time curled up in a ball, rolling back and forth.

After being in the cell for three and a half hours, Lewis began rolling violently and shaking. An hour later, someone dropped a bag of food through the hole in the door. Lewis never touched it.

Occasionally, someone passed by the window but it’s impossible to tell from the video − which shows only a limited view of the hall − whether someone was checking on him.

Presumably, jail staff could monitor Lewis’ cell in real time, said Dan Stanley, Byrum’s attorney.

After nearly five and a half hours in the cell, Lewis defecated and removed his clothing. Over the course of the next three and half hours, he rolled around in it constantly. It can seem like inexplicable behavior, but it’s a not uncommon reaction by people suffering mental breakdowns while isolated in a cell, and a well-known response to trained jailers.

Jailers employ a restraint chair and leave Lewis on a gurney

Lewis was taken from the holding cell to shower off, then moved to a different holding cell. There, he beat the window so severely that the glass began to crack, so jailers put him in a restraint chair and strapped down his arms, legs and chest. This, the jailers said, they did partly for his own safety and partly to calm him down.

And that’s how Lewis stayed for nearly two hours, pulling at the straps the entire time. After roughly 90 minutes, someone shone a flashlight on his face through the window, presumably checking on him, but no one visited him in the cell. If someone was watching him from the window, the video from the room does not show it.

Around 8:30 p.m. jailers took Lewis out of the restraints and allowed him to use the bathroom. They placed him back in what appears to be the same holding cell with the cracked window and gave him water.

Knox News has no video of what happened over the next two hours, but at the end of that time jailers found Lewis “minimally responsive,” or code blue. An unnamed nurse said Lewis was fine five minutes before, according to body camera footage reviewed by Knox News.

After about 12 minutes of nurses performing CPR, Rural Metro emergency crews arrived at 10:51 p.m. They also performed CPR before placing Lewis on a gurney and wheeling him away 15 minutes later.

Less than 24 hours after he called police, Ricky Lewis was all but dead. He arrived at the University of Tennessee Medical Center in a state his daughter described as “brain dead,” and died at 4:23 p.m. May 26 after his daughter made the wrenching decision to remove his life support.

“I will never forget this because I had to live through it,” Byrum said. “I have to live with it every day knowing that my dad got treated like s— for the last 18 hours of his life. He died in that jail. And I know that for a fact.”

Expert says Lewis’ treatment was ‘unconstitutional’

Experts in incarceration said Lewis never should have been left alone in his state.

Marc Bullaro is an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He retired after 29 years of service with the New York City Department of Corrections, leaving as an assistant deputy warden.

The medical staff could have − and probably should have − called 911 when Lewis arrived at the facility and wasn’t responsive to treatment, Bullaro said. It could have saved his life.

Marc Stern is a professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Washington and a jail health care consultant. The system − jail staff and nurses − failed Lewis, he said. An ambulance, or a doctor at the very least, should have been called.

“There was a responsibility for figuring out what was going on, and ignoring someone who had a sudden change of behavior is unconstitutional at the very least … they have a constitutional obligation to provide medical care and they failed to respond,” Stern said.

At least one person − Corrections Lt. William Howard − thought Lewis’ state was concerning enough that he should have been sent to the hospital, according to Lewis’ medical screening form obtained by Knox News. But a nurse within the jail ruled Lewis was fine, signing off on the report at 6 p.m., 20 minutes before he was placed in the restraint chair.

“PER CORRECTIONS INMATE WAS BROUGHT TO MEDICAL FOR MONITORING,” nurse Herbert Trent wrote. “INMATE APPEARS TO BE IMPAIRED BY ILLICIT SUBSTANCE. INMATE REPORTS BEING ON A 3 DAY METH HIGH. HE CONTINUES TO CURSE, YELL, LAUGH, HIT THE CELL DOOR BUT IS HEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE. WILL MAINTAIN INMATE IN SMALL HOLDING UNTIL DEEMED APPROPRIATE TO HOUSE IN GEN POP OR MH HOUSING. WILL PASS ON TO ONCOMING SHIFT.”

Stern said it appears the jail staff did what they were supposed to do − alert medical professionals − but they could have called for an ambulance for Lewis even if the nurse cleared him.

Separately, Bullaro said, no person should ever be left to roll in their own feces. It happens and he’s seen it, he said, but beyond getting the necessary equipment to handle the situation and care for the inmate, the person should be attended to within 20 minutes tops.

“They should’ve taken some more medical care and of course mental health care. Not to mention, just as a matter of humanity and decency, stopped him from rolling around the floor in his own feces for three or four hours … to have that go on for several hours is unreasonable,” he said. “You have to have some problems to roll around in your own feces. That’s not something even someone who is acting is going to do.”

Byrum’s attorney, Dan Stanley, put it simply: the jailers and nurses simply didn’t care.

“So, you’re going to look at both whether or not he’s had a serious medical condition, which I think anybody can see there’s definitely a serious mental condition going on,” he said. “And then you look at their actions and say any reasonable person (could see) they obviously didn’t give a shit. The inaction was obvious. You don’t have to beat them, just let them sit there and writhe in pain … any objective person would say that’s not right.”

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation typically investigates an inmate death, but only at the request of the local district attorney’s office. Knox County District Attorney Charme Allen did not request an investigation into Lewis’ death.

Knox County Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman Kimberly Glenn told Knox News on June 12 she had forwarded 13 questions about Lewis’ incarceration and death to Sheriff Tom Spangler and Chief Jailer William Purvis. Neither responded to the questions, including how jailers monitor incarcerated people, whether Lewis’ death was reviewed and how many deaths have occurred at the jail in the past five years.

Lewis’ daughter pushes for justice

Life without her dad will always look different for Byrum, there’s no changing that. No more phone calls or celebrations. Lewis was planning on taking her children fishing, but that won’t happen.

Her dad meant something, she said. They had their differences, but he was at the center of her life. Now she is hoping his story will force officials in Knox County to look at how inmates are treated, especially those experiencing mental health complications.

“I feel like there should be justice because I’m pretty sure my dad isn’t the only one. These officers and these nurses need to be trained on how to handle somebody who is an addict, that has mental health (issues),” Byrum said. “That’s what’s wrong with a lot of places. Because they’re not properly trained to handle people with crisis. All they see is they have the authority to treat somebody however they want.

“It shouldn’t be like that. These people are humans … An animal was treated better than what my father was and those videos prove that.”

Tyler Whetstone is an investigative reporter focused on accountability journalism. Connect with Tyler by emailing him at [email protected]. Follow him on X, formerly known as Twitter, @tyler_whetstone.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Was Ricky Lewis’ solitary death in Knox County jail cell preventable?

Source Agencies