Key Points

- Asylum seeker Asif Ali Bangash says he’s been ‘left behind’ with no visa certainty, work rights or Medicare access.

- He relies on handouts from charities and often works ‘exploitative’ jobs to get by.

- Refugee advocates say living ‘in limbo’ for prolonged periods can take a toll on an asylum seeker’s health.

Asif Ali Bangash was 22 when he left his home in Parachinar, a city in eastern Pakistan that shares a border with Afghanistan.

As a minority Shia Muslim in that region, he said he faced the possibility of abduction and target killings every day, which contributed to his decision to take up the arduous journey to Australia by boat.

“In my mind, it was all about seeking a country that respects and upholds human rights and offers protection against discrimination and abuse,” he told SBS Pashto.

“When I arrived in Australia, I hoped for a chance to rebuild my life, contribute to society, and find a place to call home. But the path has not been easy.”

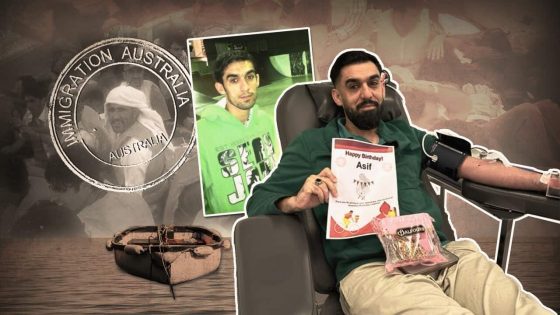

Asif Ali Bangash in 2012 (left) and in 2024. Credit: Supplied

Bangash obtained a bridging visa after arriving, though subsequent attempts to secure a visa that would place him on a path towards permanent residency, have been rejected.

His most recent application for a Bridging E visa – which has been seen by SBS Pashto – was rejected as he did not satisfy provisions of the Migration Regulations 1994.

As he’s unable to return to Pakistan due to threats to his life amid he’s launched a last-ditch effort to avoid deportation by requesting intervention from Immigration Minister Andrew Giles, a decision that remains pending.

Due to his status, he does not have work rights, coverage by Medicare and access to education opportunities, placing restrictions on his “ability to live a dignified life” and in a “constant state of limbo,” he said.

“It’s incredibly frustrating and disheartening not to have work rights or a [permanent] visa, especially when others from similar backgrounds have been granted these,” he said.

“I depend on the kindness of friends [with legal status] for food and shelter.

“Despite these challenges, I have experienced kindness and solidarity from many Australians who believe in the values of compassion and justice.”

This year, Bangash turned 34 and he decided to donate blood, which he said was his way of supporting the community.

Asif Ali Bangash decided to donate blood on his 34th birthday to “give back” to his community. Credit: Supplied

Despite the time that has passed, he said his home city in Pakistan remained “unstable”.

“Living in such a precarious state has taken a severe toll on my mental and emotional well-being.

“Watching others from my community receive visas while I remain in limbo is disheartening.”

Khalid* is in a similar position as a Shia Muslim who arrived in the same boat as Bangash in 2012.

Both men arrived before 2013 and were sent to an onshore immigration centre for processing.

Khalid said he left Parachinar due to “significant threats” to his life by terrorist organisations such as the Pakistani Taliban and Sipah-e-Sahaba who remain active in the region.

The majority of his friends who arrived in Australia at the same time had already been granted permanent visas enabling some to reunite with family members, he said.

He was initially granted a bridging visa when he was released from the onshore detention centre in October 2012, though subsequent visa applications have been rejected as he didn’t satisfy the provisions of the Migration Regulations 1994.

He now plans to seek ministerial intervention in his case to avoid deportation.

“I believe that it’s not fair, as we are from the same place with the same situation. We all should have been granted protection visas,” he said.

“Life is very hard here, as I have no work rights. As we all know, things can get really rough financially without a stable income, so most of the time I am borrowing money from my friends.”

According to the Refugee Council of Australia, there are approximately 7,453 people, like Bangash and Khalid, who arrived by boat in 2012 or 2013 and have received negative decisions on their visa applications.

‘Exploitative’ jobs and ‘destitution’

Dulce Munoz has been an asylum seeker advocate for eight years.

She believes it is a “fundamental human right” to seek asylum and granting visas and work rights is “essential” for an individual’s integration into the community.

“Many of these individuals live under precarious conditions on temporary visas without work rights. This forces them into exploitative jobs and makes them heavily reliant on charities,” she said.

“We urge Australians to better understand the realities faced by people seeking asylum.

“These individuals are often excluded from basic rights such as the ability to work and access to Medicare, making them vulnerable to exploitation and adversely affecting their general health.”

Asylum seekers protest in front of the office of Home Affairs Minister, Clare O’Neil MP, demanding permanant visas. Credit: Supplied

Refugee Council of Australia’s chief executive Paul Power said most people who have applied for asylum in Australia do not have a “safety net and are ineligible for government-funded support services”.

He added that asylum seekers had no access to work rights or Medicare due to a delay or refusal to renew bridging visas or through federal government policy.

“They rely on community groups for charity or work in exploitative conditions. Without income support, people are often desperate to undertake any work in order to survive and provide for their family,” he said.

Many people seeking asylum without legal status are living in deep poverty and destitution.

Paul Power, Refugee Council of Australia

“Many people seeking protection experience mental illness due to their uncertain migration status and asylum experience, including, in many cases, prolonged immigration detention and family separation.

Power added that frontline asylum support charities and community groups cannot meet the demand for their services.

“The Australian government should ensure that people seeking asylum have equitable access to services and support.

“The Australian government should also ensure that all people seeking asylum remain on a visa with work rights while they remain in the country.”

SBS Pashto contacted the Department of Home Affairs for comment but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

*Not his real name