Key Points

- Formerly a veterinarian in South Korea, Hyojin Yang’s passion for bats led her to Tolga Bat Hospital in Far North Queensland.

- Tick paralysis is a threat to Australia’s endangered spectacled flying fox.

- Bats play a crucial role in the country’s biodiversity and ecosystem health.

“Spectacled flying foxes have slightly brown areas around their eyes as if they were wearing glasses. As their name suggests, they sometimes look like foxes or dogs,” she said.

Inspired by a previous visit to Tolga Bat Hospital in Far North Queensland, she decided to become a volunteer there, caring for baby bats.

Jenny Mclean (second from left), the director of Tolga Bat Hospital, and Hyojin Yang (fourth from right). Source: Supplied / Hyojin Yang

The hospital, located an hour inland from Cairns, sits in an ecological hot spot, its director Jenny Mclean explained.

“We have got a World Heritage rainforest, (and) the World Heritage Great Barrier Reef right there. So, in this area, we have about half of Australia’s bat species, and we mostly get spectacled flying foxes coming into care, and they’re listed as endangered,” she said.

Tackling tick paralysis

“We will find and remove the tick, and then we treat (the bat) with a very expensive tick anti-serum, the same as a cat or a dog would get treated. And then it’s good nursing care after that,” she said.

A baby spectacled flying fox on the mend at Tolga Bat Hospital. Source: Supplied / Tolga Bat Hospital

However, in some cases, the bats are entirely covered in fly eggs and maggots, and then must be euthanised immediately to end their suffering.

“So the baby bats are trying to cling to each other and even coming towards volunteers. I have felt that they need me, and I have felt a maternal love that I thought I didn’t have, and it was a touching moment,” Yang said.

Spectacled flying fox pups being cared for at Tolga Bat Hospital. Source: Supplied / Hyojin Yang

In December, baby bats begin to wean off the bottle and start eating solid fruits in a large cage.

“We give names to each of them and build a great deal of affection. It is a very mixed feeling when they leave us,” Yang said.

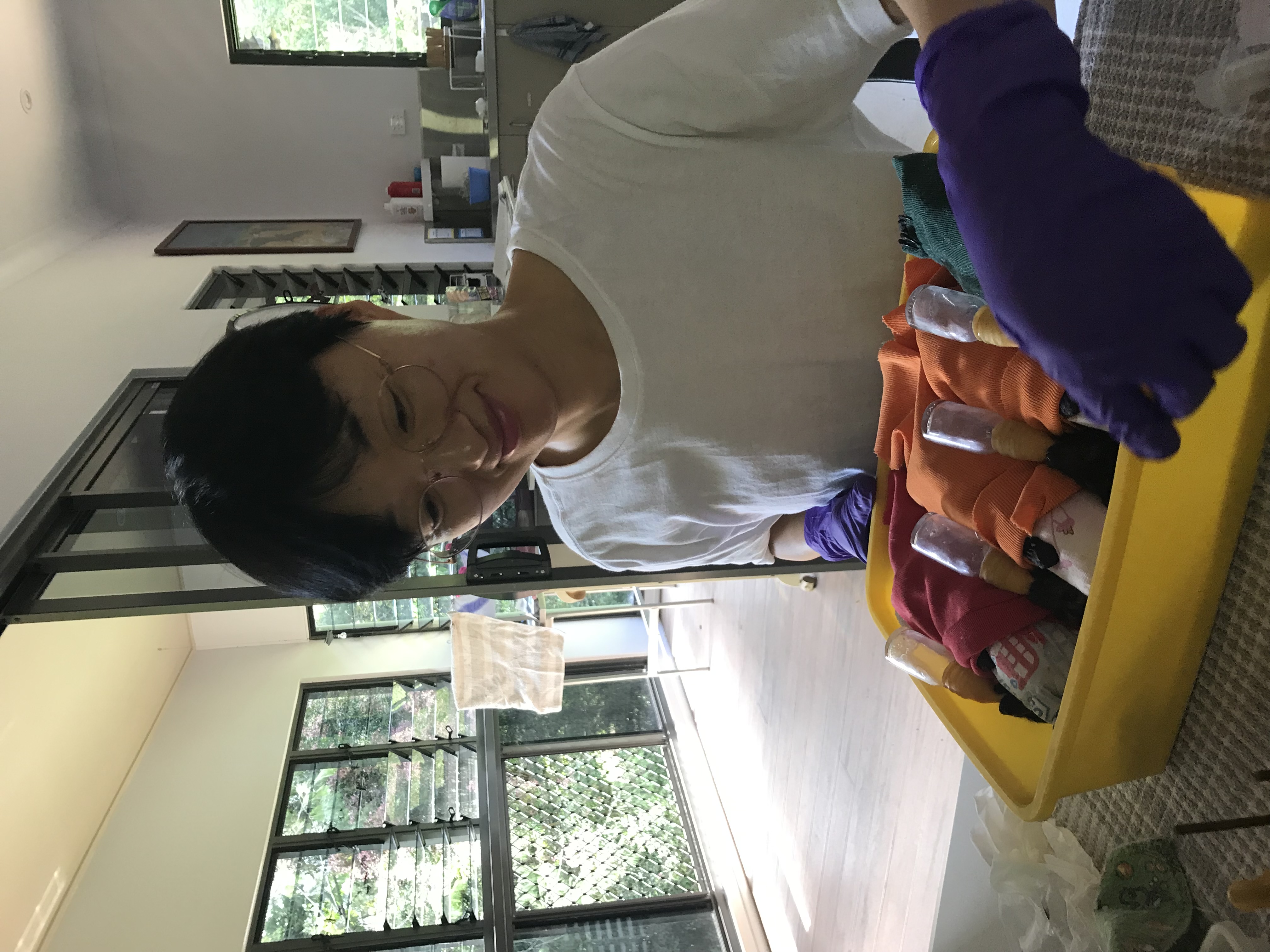

Hyojin Yang looking after baby bats in Far North Queensland. Source: Supplied / Hyojin Yang

In 2022, following a year of volunteer service, Yang joined Dr Lee McMichael’s research project at the University of Queensland, funded by WIRES grants.

The team investigated treatment outcomes for spectacled flying foxes affected by tick paralysis, achieving higher release rates with oxygen therapy in 2022 and record releases in 2023.

Poor public image

“Now that horses are vaccinated, it’s a very rare disease. I think there’s been one horse last year with it and one horse the year before. You cannot get it (Hendra virus) from a bat. You can only get it from a horse,” she said.

Tolga Bat Hospital helps flying foxes affected by tick paralysis. Source: Supplied / Tolga Bat Hospital

Lyssavirus is a rabies-like virus. Infection can occur if you are bitten or scratched by a bat carrying the virus, typically within a few days before the bat passes away from it.

“Wash the wound, go to the doctor, and discuss the fact that you’ve been bitten or scratched, and they’ll decide if you need to get the vaccination. So it’s completely preventable,” she said.

A baby spectacled flying fox at Tolga Bat Hospital. Source: Supplied / Tolga Bat Hospital

Mclean stressed that the best approach with bats is to avoid touching them.

“There’s this huge disease image around bats, but more people die every year from falling off horses or cat-dependent diseases. There were three deaths in 30 years from lyssavirus, and none of them knew what to do,” she said.

‘Without bats there would be no koalas’

Mclean highlighted that bats’ long-distance flight ability allows them to transport pollen to trees up to 100 km away, crucially enhancing genetic diversity and forest health.

Hyojin Yang worked for Seoul Zoo as an animal behaviour coordinator. Source: Supplied / Hyojin Yang

Yang, who has travelled extensively through Europe and Asia, observed that funding for wildlife is insufficient globally.

“We’re in a small regional area. We’re not in a city where you’ve got the capacity to attract a lot more volunteers. And we do very well attract international volunteers,” she said.

Source Agencies