Foreign law enforcement officers began arriving in Haiti on Tuesday, more than a year and a half after the prime minister there issued a plea to other countries for help to stop the rampant gang violence that has upended the Caribbean nation.

Dozens of armed men in military fatigues filed out of a Kenya Airways plane at Haiti’s Toussaint Louverture International Airport in the capital, Port-au-Prince.

The officers are part of a deployment of officers from eight nations who will fan out across the capital to try to wrest control of the city from dozens of armed groups that have attacked police stations, freed prisoners and killed with impunity.

The arrival of an initial group of 400 Kenyan officers came on a day of intense and deadly violence in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, as the police clashed with demonstrators protesting a tax bill that would increase taxes on many basics.

Some security experts say the Kenyan officers face a significant challenge supporting Haiti’s police and facing off with well-armed and highly organized Haitian gangs that have seized control of much of Port-au-Prince and had vowed to fight the Kenyans.

Kenya’s police also have a checkered history back home, accused by human rights groups of killing and abusing civilians, raising concerns about their actions in Haiti.

Since Haiti’s appeal for international help went out in October 2022, more than 7,500 people have been killed by violence — over 2,500 people so far this year alone, the United Nations said.

With a weakened national government and the Haitian presidency vacant, dozens of gangs have put up roadblocks, kidnapped and killed civilians, and attacked entire neighborhoods. About 200,000 people were forced from their homes between March and May, according to the United Nations.

The Kenyans in Haiti are the first to deploy of an expected 2,500-member force, an effort largely organized by the Biden administration.

“You are undertaking a vital mission that transcends borders and cultures,” President William Ruto of Kenya told the officers on Monday before they left.

The officers are expected to tackle a long list of priorities, including retaking control of the country’s main port and freeing major highways from criminal groups that demand money from drivers.

“Gang checkpoints on these roads are also a major source of their income,” said William O’Neill, the U.N.’s human rights expert on Haiti.

“While much delayed, the arrival of the Kenyans comes at a good time,” particularly since a new police chief and prime minister have been named in recent weeks, he said.

The United States has provided many of the mission’s supplies, rushing to find armored vehicles and other equipment.

“The Kenyans do not want to be one of these missions that show up on the ground and, for a month, they never leave their base,” Dennis B. Hankins, the U.S. ambassador to Haiti, said in an interview.

The Kenyans, he added, will need to “support” the Haitian police, but not replace them, so that when the mission ends their departure doesn’t create “a security vacuum.”

Officially called the Multinational Security Support Mission, the deployment is expected to last at least a year, according to the U.S. government. Sanctioned by the U.N. and mostly financed by the United States, its goal is to support the Haitian police and establish enough stability so the transitional government can set up elections to choose a new president, as well as members of Parliament.

The U.S. military has flown more than 90 flights into Haiti ahead of the mission, carrying more than 2,600 tons of supplies. Civilian contractors have been building sleeping quarters for the Kenyan officers at the Port-au-Prince airport.

In May, Haitian government officials began clearing the airport perimeter of hundreds of houses, which had made it easier for gangs to hide and fire at aircraft, forcing the airfield to close. The airport has reopened to commercial flights.

The gangs, the ambassador added, did not fight back while preparations at the airport were made, a sign that perhaps they may not be willing to engage in direct combat with specialized forces, he said.

“As soon as we got the airport open and functional and we started seeing military flights, that had a real significant psychological impact on the population,” Mr. Hankins said.

Many experts say that beyond security Haiti needs a comprehensive plan to address the root causes of its governance problems.

After Prime Minister Ariel Henry was forced to resign in late April, it took several weeks for political parties to agree on who would serve on a new transitional presidential council.

It was a full month before a replacement for Mr. Henry took office.

Garry Conille, a former U.N. official, accepted the post in late May.

In a social media post late Monday, he said he hoped this mission would be Haiti’s last. The country has a long history of international interventions, including some that were marred by accusations of sexual exploitation and poor sanitation that led to widespread cholera.

So far, the Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Benin, Chad, Jamaica and Kenya have officially offered personnel for the mission.

But the mission has not received much financial commitment.

While Kenyan officials estimate the cost will run up to $600 million, a U.N. fund to pay for it has only $21 million. The United States has pledged more than $300 million to finance the mission.

The United States, Canada and France — Haiti’s biggest benefactors and allies — were unwilling to send troops of their own to Haiti.

Kenya was the first nation to publicly offer to do so. Many experts believed the mission would be more welcomed if was led by an African nation.

Experts say that Mr. Ruto, who won the presidency in 2022 after a closely contested election, was using the deployment to further boost his profile on the global stage.

The deployment comes even as Mr. Ruto faces widespread protests nationwide against a finance bill that critics say will increase the already high cost of living.

On Tuesday, the police fired tear gas and shots were heard as thousands of demonstrators flooded the streets around Kenya’s Parliament in Nairobi. Human rights advocates said that at least five people were killed and over 30 others wounded.

A team of Haitian police commanders recently visited Nairobi while Mr. Ruto held talks with the Haitian transitional presidential council.

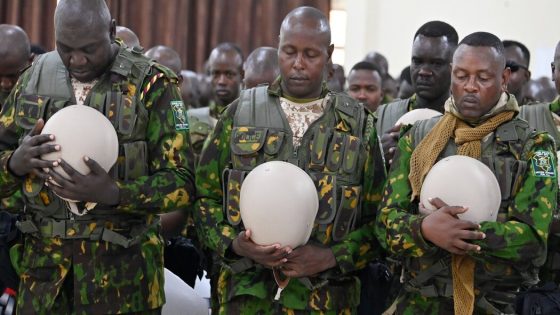

At a police camp in Nairobi, officers have undergone physical and weapons training and received new helmets and body armor, according to interviews with officers who spoke on the condition of anonymity, because they were not authorized to speak publicly to reporters.

They have also taken intensive French and Creole courses.

Beyond protecting key infrastructure, the officers at some point will be expected to secure the presidential palace, which remains in shambles after a 2010 earthquake but continues to be a symbolic place of power in Haiti.

But the contingent of 400 that arrived Tuesday is just a small step toward a large operation that will require many more people and resources to be effective, said Gédéon Jean, the executive director of the Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights, a Haitian organization that was forced to suspend its operations because of rising violence.

“So much remains to be done,” Mr. Jean said.

The initial group is likely to “play it safe” at the start, but even as more officers arrive from other countries, their task will be daunting, particularly since they have not worked together before, do not speak the same languages or have a shared “operational framework,” said Sophie Rutenbar, a visiting scholar at the New York University Center on International Cooperation who has worked in Haiti.

“The early deployment of this force is going to be very vulnerable,” Ms. Rutenbar said.

Eugene Chen, a former U.N. official who follows Haiti closely, said the international mission seemed to emerge out of a desperation to do something. Without finding ways to support Haiti’s political process, the mission could exacerbate the violence, Mr. Chen said.

“It’s not clear,” Mr. Chen added, “that this is the right answer.”

Andre Paultre contributed reporting from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and David C. Adams from Miami.

Source Agencies