By Marianna Spring, Disinformation and social media correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was just hours before the polls opened for the UK’s general election when I noticed the audio clip going viral on the social media site X.

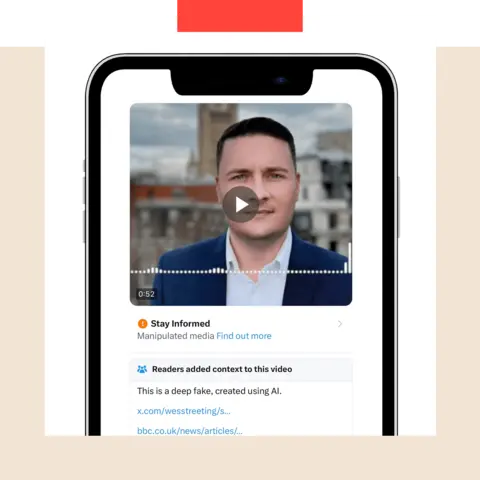

It sounded like Labour politician Wes Streeting using foul and abusive language towards a member of the public who disagreed with him over the war in Gaza.

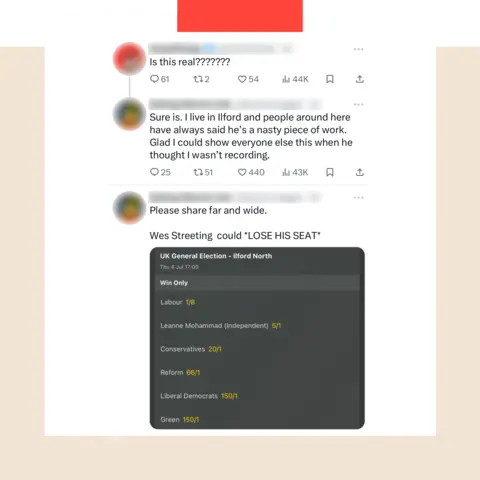

There were replies from other accounts, apparently reacting in shock: “Is this real???????”

It wasn’t. The incident never happened.

That did not stop the false audio clip – since labelled on X as “manipulated media” – racking up more than a million views.

By itself, the clip wasn’t necessarily enough to mislead voters.

But crucially, a network of profiles run by real people commented on each other’s posts in support of the fake clip. This had the effect of lending it credibility as well as amplifying it to more people.

The poster who asked whether it was real was connected to this group of accounts, as was the user who replied to insist that it was.

As a result of both the clips and these comments, some real users I contacted told me they were confused about what to trust.

Streeting himself even said that he had been contacted by another politician who initially believed the clip was real.

It’s not just about deepfakes…

Earlier in the election campaign, I had investigated this network – a group of left-leaning activists who had shared several other deceptive clips smearing not just Streeting, but other Labour politicians and some from Reform UK too.

Some of these clips were clearly absurd and satirical – a form of trolling – but others falsely portrayed candidates as saying politically damaging things.

There had been warnings from politicians and social media experts that the integrity of this election would be undermined by deepfakes – AI-produced video and audio that manipulate a person’s voice or image to say or do things they never said or did.

But the broader issue I encountered was that some committed political activists have learned to distort, manipulate and shape the online conversation with all the tools at their disposal including, but not limited to, AI.

…and not all ‘deepfakes’ are sinister

I tracked tactics like this on social media feeds during this election campaign using dozens of old phones, which were set up with the profiles of my 24 undercover voters.

They are fictional characters, based in locations across the UK, that I created based on data and analysis from the National Centre for Social Research. Their profiles are set to private with no friends.

What appears in their feeds cannot give me a complete picture of what everyone has been seeing this election campaign – they aren’t part of private group chats, for example.

But they have offered me an insight into how voters are targeted and what content they are recommended by the major social media platforms.

The undercover voters’ feeds have been greeted not by a tsunami of AI fakes, but rather by a deluge of political posts from activists, supporters and unidentified profiles amplified by the social media sites’ algorithms and at times with hate directed at politicians in the comments

And AI fakes are not always not always created with malicious intent. Sometimes they are used for the purposes of humour or parody.

In one example, a series of videos purported to show Sir Keir Starmer, Rishi Sunak, Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson playing each other at the video game Minecraft. It’s unlikely anyone seriously believed these were real.

The average person can out-do political parties

A lot of the content that really took off this campaign was not paid-for targeted adverts, but posts picked up by social media algorithms designed to identify the most engaging content and push it into people’s feeds.

Cue funny memes, TikTok trends and selfie videos about parties’ policies – the less slick, the better.

It means that lots of the posts popping up on my undercover voters’ feeds have been from people I like to call the accidental election influencers, who have been plucked from obscurity by the algorithms.

Hear more about the UK undercover voters and how this election unfolded on social media on BBC’s Newscast podcast.

They have a range of political views and their amateur content was getting as much traction as some of the parties’ own posts – and more than some of their online ads.

Crucially, these posts could reach an audience who were otherwise disengaged from mainstream politics.

Sometimes they provided reliable updates, but on other occasions they were responsible for misinformation, too – such as a faked image of Sir Keir Starmer in a Palestinian flag T-shirt or a post falsely suggesting that an incident in which a milkshake was thrown at Nigel Farage while he was out campaigning had actually been staged.

Reform UK dominated social media feeds

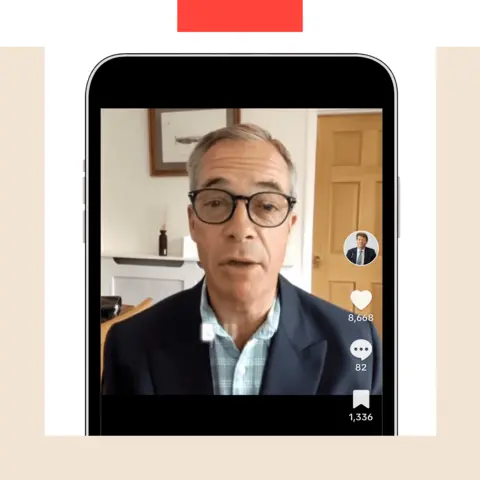

It is worth saying that some of the political parties have had success at producing viral posts. Reform UK in particular has generated a huge amount of traction and conversation on social media.

That is backed up by what I have found on both the feeds of my younger undercover voters, and in my conversations with real younger people.

As well as being pushed left-leaning content connected to Labour and the Greens, some of their feeds have also been awash with posts from Reform UK.

It is mainly young men who have told me me about how their feeds were dominated by posts about Nigel Farage’s party.

A lot of this shows the success of Reform UK – both the party itself and also its supporters – at dominating the online conversation and creating content that resonates with this audience, discussing housing, immigration and other issues in a very clear and direct way.

Reform UK was also one of few parties that had already started to build its TikTok reach before this general election, as had its leader Nigel Farage.

Don’t underestimate the comments

A very active network of users was also willing to post in support of Reform UK, either with their own videos and content or in reply to others.

While an earlier generation of internet users would warn each other to “never read the comments”, they can be a place users go to gauge the opinions of others – just as we saw with the network of profiles that boosted the fake Wes Streeting video.

In the comments of political videos during the campaign, it was common to see the words “Vote Reform UK” repeated over and over again by different accounts, suggesting the party had a wave of support behind it.

I investigated several profiles accused by some other users of being bots, tracking down and identifying who was behind them.

And as I’ve found in previous investigations, many of them turned out to be run by real voters who were indeed posting the same political messages again and again, from an anonymous profile that may have looked like a bot but was actually just their own account, to support the party.

Others were suspicious, though, and some of those have been removed by the social media companies.

A spokesman for Reform UK told me the party was “delighted about the organic growth of online support” but also said there were other fake accounts, not linked to the party, which it had flagged by itself to the social media companies.

Trying to pinpoint exactly who is behind suspect accounts is very difficult. I’ve established for myself that some of them really are political supporters who have decided not to share their identities. It’s possible that groups of political supporters might also get together to run fake accounts to push their preferred party’s ideas.

Alternatively, the accounts could be trolls seeking to make the party look suspicious. Or they could be spammers, jumping on a popular topic and eventually hoping they can use it to sell stuff.

Or they could be run by a group, such as a hostile foreign power, seeking to sow division or cause trouble.

But while there have been documented attempts by countries such as Russia to use fake accounts in this way, there is less evidence that they have ever changed anyone’s mind.

It’s not just a problem at election time

This concern over the risk of foreign influence has prompted social media companies – TikTok, X and Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook – to invest in measures they say will protect users from online manipulation.

This election, they have all told me, they have tried to ensure users get reliable information. Some have removed posts and accounts following my various investigations.

During the 2024 election, for the first time since Elon Musk took over X, the social media site responded to allegations raised by me – and took action, too.

But lots of the tactics I’ve uncovered were deployed and finessed by political activists long before Rishi Sunak stood in the pouring rain to call the general election.

The group of accounts sharing the faked clips and false comments about Wes Streeting had shared similar posts about Keir Starmer, for example, during a by-election back in February 2024.

As someone who investigates social media’s real-world impact all year round, it feels like some of the companies often only really wake up and take action during an election period.

The problem is that the concept of the “social media election” is dead. Instead, the world is constantly shaped by what’s happening on our feeds and group chats long before and long after any vote.

And so in the end this wasn’t a deepfake election – it was an election in which the same old questions about social media regulation went unanswered. The warnings about AI were a distraction from the lack of clear solutions to problems posed by algorithms and well-practised misinformation tactics online.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Source Agencies