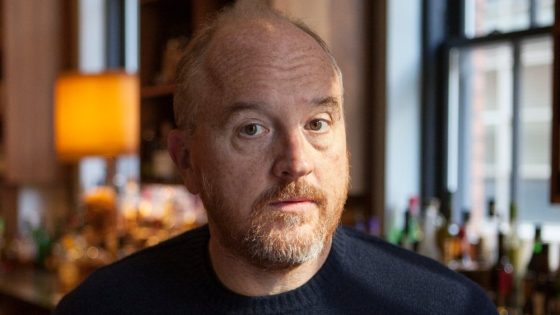

The title of “Sorry/Not Sorry,” a documentary about the Louis C.K. scandal, makes the film sound like a hot-button exposé with the potential to be as controversial as the case itself. The offscreen infamy of Louis C.K. — his coercive and abusive ritual of masturbating in front of women, many of whom were his comedian colleagues — was first revealed in the mainstream media nearly seven years ago, amid the tidal wave of reckoning that became #MeToo. I thought: Is the film going to be about how Louis C.K. is now sorry…and not sorry? And what point-of-view will the documentary take?

“Sorry/Not Sorry” does deal with Louis C.K.’s reaction to the scandal: his message of apology that was never quite an apology; his carefully orchestrated comeback, after only nine months, via the comedy-club circuit (a comeback that ultimately encompassed his winning a Grammy for best comedy album in 2022 and performing a concert in the round at Madison Square Garden); and how he dealt with the repercussions of his behavior within his stand-up act (short version: He’s not sorry).

But that’s all covered in the last 20 minutes. Most of “Sorry/Not Sorry” tracks the 15 or so years leading up to 2017. During that time, Louis C.K. was becoming the most powerful figure in stand-up comedy, launching his fabled series on FX, and (offstage) indulging in his reckless behavior without fear of recrimination, because the whole comedy world was protecting him. The documentary is a production of the New York Times, and as directed by Caroline Suh and Cara Mones, it’s a meticulously sharp, responsible, and absorbing movie — an incisive study, really, of the sweep-it-under-the-rug culture that was firmly in place before the #MeToo revolution knocked some of its foundations askew. But the movie is also asking larger questions.

Early on, we see a clip from “Charlie Rose,” in which Charlie, seated opposite Louis C.K., tells the comedian that he’s been compared to Lenny Bruce and Bob Dylan, anointed as a “philosopher king.” C.K. grins with humblebrag sheepishness (he’s clearly flattered) and then says, “I’m just a comedian.” The clip made me cringe, though not just because of what we now know he was hiding. C.K., by that point, had become a culture hero, yet if I can part ways with the culture, I always found him to be a clever but fundamentally overpraised comedian.

“Louie,” on FX, was greeted as the second coming, but to me it was the weekly version of an “edgy” indie film that had stray nuggets of squirm-factor hilarity but insisted, in every episode, on breaking up what was best about it — its air of authenticity — with overstatement and contrivance. It annoyingly straddled the line between prickly reality and sitcom fakery. If it had been an indie film, it would have come and gone without fanfare. But on the small screen, the show somehow passed as Revolutionary Popular Art.

I’m generally a staunch advocate of separating the art from the artist. Yet part of what came into focus after the Louis C.K. scandal is that in my (admittedly minority) opinion, the reason he struck me as a gifted but limited comedian was not because he wasn’t a smart and funny man, but because his view of the universe was so blinkered. I remember seeing him do a routine about getting ready to go on vacation with his family, and he describes walking around the van feeling something like: This is the last moment of pleasure and freedom I’m going to have for a week. I can get as impatient with my family as anyone, but I thought: Really?! You don’t even like going on vacation with them? I’m sorry, that’s not a “typical” inside-the-mind-of-a-bro-geek reaction — it’s warped. It’s the thought of someone who isn’t happy in his own skin. And I thought: It’s absurd that he’s generalizing from that. Louis C.K. always comes on like he’s touching universal chords in the tradition of Richard Pryor and George Carlin, but really he’s unpacking a distorted POV.

No question, though: He had talent, he pushed the envelope, and he wrapped his observations in a confessional aura that often had more resonance than what he was actually confessing. He became the superstar of angry brainy white-guy angst, and he knew that his superstardom protected him. After the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke, there was much discussion of who knew what and when they knew it, and while it was obvious that Weinstein had been shielded for years by those around him, and by the whole entertainment industry, I do believe that relatively few people knew the horrific extent of his crimes.

In the case of Louis C.K., his transgressions were far less extreme, but as the documentary reveals, they were incredibly widely known. The incident that became iconic occurred at the Aspen Comedy Festival in 2002, when C.K. invited two comedians, Dana Goodman and Julia Wolov, to his hotel room and, once there, asked if he could take his penis out, which they first thought was a joke. They gave no consent. He got undressed and masturbated, and they were horrified and felt paralyzed. They finally fled, and he called out afterward, “Which one is Dana and which one is Julia?” That’s actually a significant line, since it’s a “comic” expression of the dehumanization his compulsive ritual was really about.

People gossip — about everything. And especially stuff like this. Louis C.K.’s pattern was, according to the movie, the comedy world’s open secret. More or less everyone knew about it and “accepted” it. It was just…what Louis C.K. did. And if you questioned it, it could kill your career. Goodman and Wolov were told to keep quiet, and the film suggests that in L.A. they were squeezed out of potential jobs by Louis C.K.’s manager, Dave Becky. Given the “Louie”-like TV series that C.K.’s company was producing (for people like Pamela Adlon and Tig Notaro), he was almost like a studio head. But the spilling-over-the-sides world of the Internet had arrived. C.K.’s behavior was cited in several high-profile blind items on Gawker. The comedian Jen Kirkman implicated him on her podcast without naming him. The truth was starting to swirl to the surface.

It all exploded, thanks to the work of Times reporters Jodi Kantor, Cara Buckley, and Melena Ryzik. But that was headline news. The film deals most intriguingly with C.K.’s incendiary, semi-under-the-radar return to the comedy world. He was able to do it by working independently, sidestepping the corporate apparatus of the networks and studios (who never invited him back). “Sorry/Not Sorry” meditates, intelligently, on the question of how the culture should deal with someone like Louis C.K. Michael Ian Black, the pensive comedian who started a controversial tweet thread about it, says, “I was like, I’m not defending Louis’s actions. I’m having, in public, a conversation that I feel like men are having in private — and women — all over this country, and saying, ‘How do we deal with this? How do we welcome people back or not welcome people back?’”

The Times critic-at-large Wesley Morris suggests, quite rightly, that Louis C.K. should have done a reckoning. Instead, C.K. treated what happened to him as simply the “outing” of his fetish, his obsession, and while he admitted that it was embarrassing, what he said to his audience (this is from a stand-up clip we see) is, “You all have your thing. I don’t know what your thing is….’Cause everybody knows my thing.” As if that’s the only thing that defines it — that it all became public. Louis C.K.’s “problem” is that he did something very wrong, but as “Sorry/Not Sorry” reveals, part of his problem is that he still has no idea why it’s wrong. I’m sorry, but that’s not someone squeezing comedy out of truth.

Source Agencies