Perrin March V knew how he wanted to die.

First, he’d enter a Jewish synagogue and chain the doors. Then, he’d kill the rabbi, detonate explosives, shoot the congregants and get shot to death by police.

In an April 2022 online chat, March called this his “dream death.”

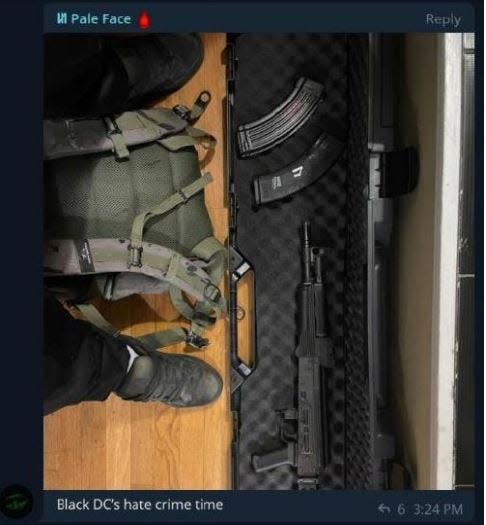

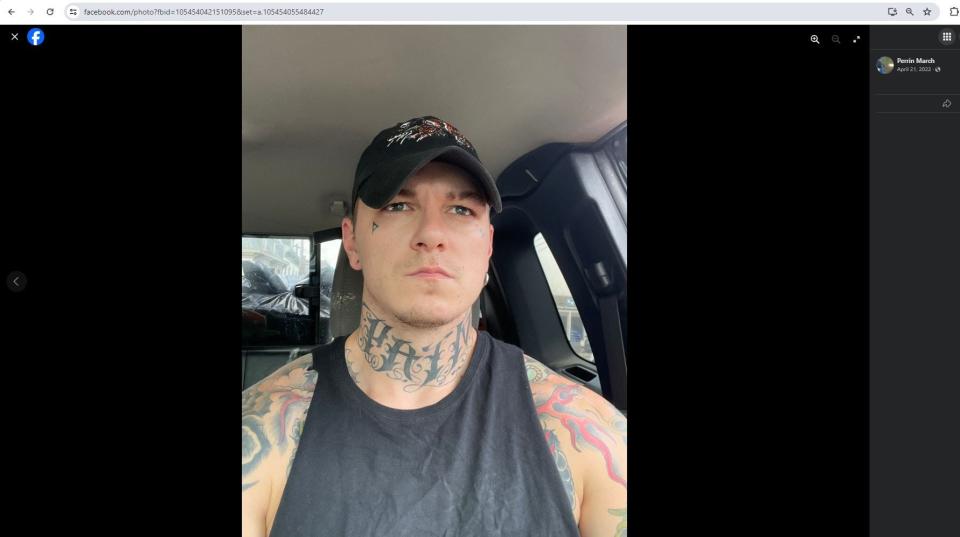

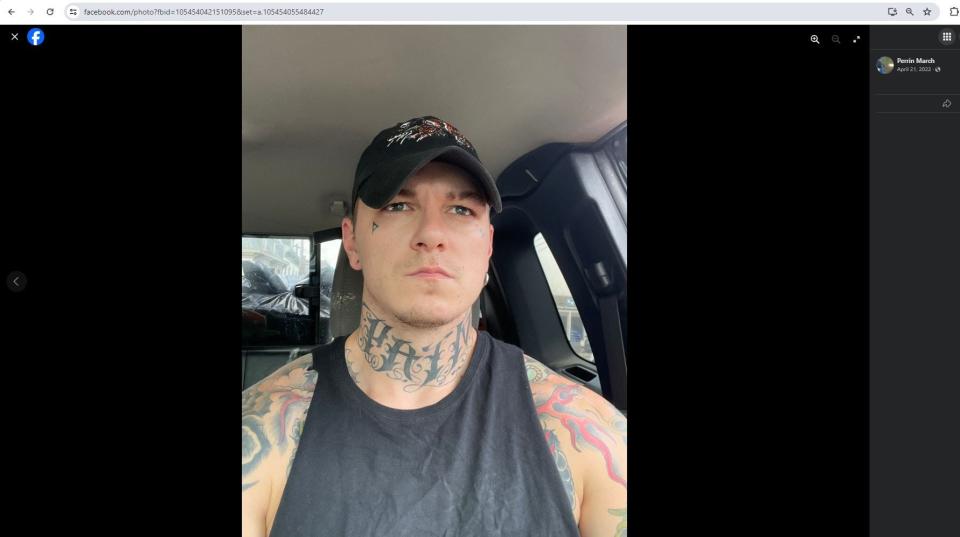

The Bellevue, Kentucky, man, who posted and chatted on Telegram under the alias “Pale Face,” later expressed disappointment that no one wanted to attack a synagogue with him.

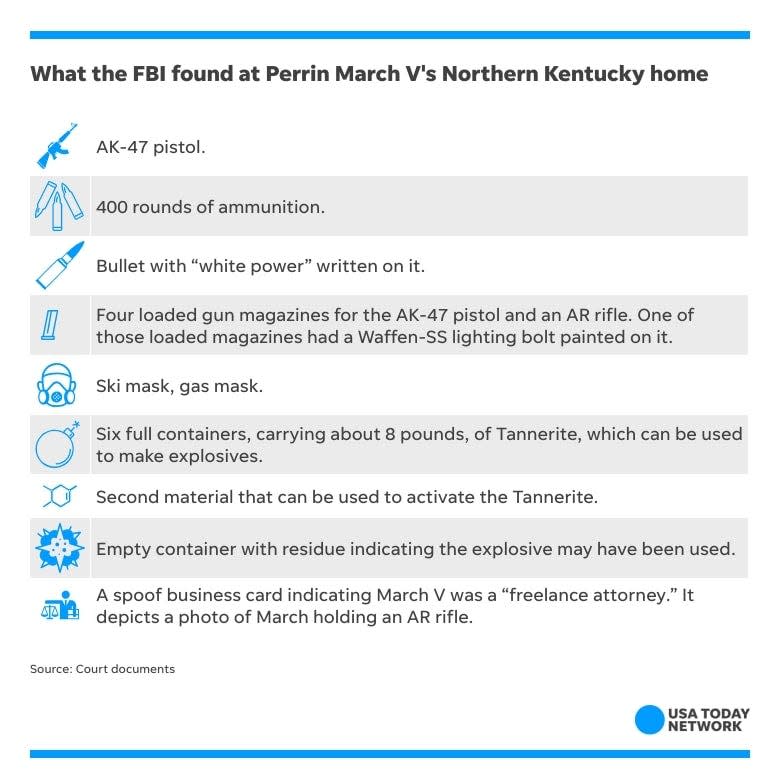

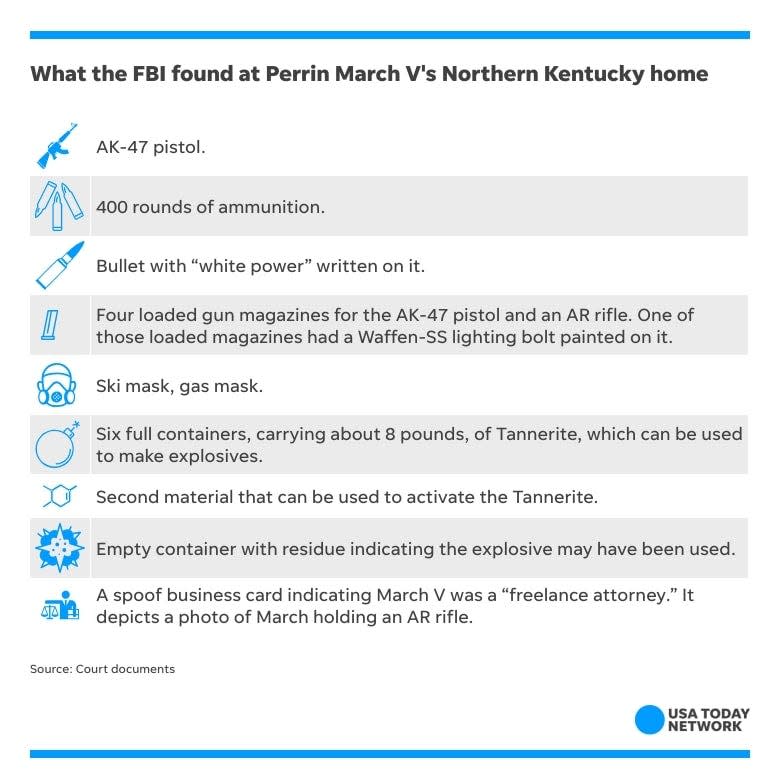

When FBI agents raided March’s home May 13, 2022, they found a gun, bullets, Nazi references and 8 pounds of a chemical that can be used to make explosives.

The scene had “all the ingredients of a mass shooting,” a prosecutor later said in court.

But March, the 29-year-old scion of a prominent and wealthy Cincinnati family, did not face terrorism charges. Instead, he pleaded guilty to illegal possession of a firearm and was sentenced to two years and eight months in prison, which was later reduced by two months.

His attorney, Eric Eckes, told The Enquirer in an email: “The family does not wish to speak with you under any circumstances.” Eckes also declined to be interviewed.

The Enquirer successfully fought for access to court records after they were sealed, blocking most documents from public view.

“Sealing is very unusual,” said attorney Jack Greiner, who represented The Enquirer. “Court documents are presumed open to public inspection so the public can oversee the operations of the criminal justice system. Mr. March argued that his privacy interests justified the sealing. The court rejected that argument.”

The records show March has a violent past – stabbing someone in the chest in 2016 and threatening to kill his girlfriend and unborn child in 2021.

They also hint at the extent of March’s involvement in online discussions about mass violence, antisemitism and Nazi ideology.

The case raises a number of questions: Why was his court record sealed? Why was an earlier stabbing charge against him removed from records? And how did the heir of one of Greater Cincinnati’s prominent families fall into the realm of white supremacy?

Meanwhile, March was released from federal custody June 28 after living at a halfway house.

Who is Perrin March V?

March is the oldest of four children raised by Diane and Perrin March IV, members of a Cincinnati family that has been active in the city’s industrial, philanthropic and society circles for more than a century. They’re both luxury real estate agents.

The March family has owned Cincinnati Incorporated, a machine tool manufacturer, for over a century. It was founded by Perrin G. March as the Cincinnati Shaper Company in 1898. It’s currently run by Perrin March V’s aunt at a 500,000-square-foot plant outside the city in Harrison, Ohio.

March grew up with his parents, who own a home in Hyde Park, one of Cincinnati’s more affluent neighborhoods. He loved animals, Lego, and Harry Potter, his mother wrote in a letter to the court.

He was enrolled at the Summit Country Day School, a private, K-12 Catholic school whose alumni include former Ohio State Sen. Eric Kearney and Cincinnati Reds president Phil Castellini.

When contacted by The Enquirer, Summit Country Day confirmed March was a student there for middle school but didn’t graduate from its upper-level school.

March was diagnosed with ADHD in middle school, and he struggled with organization, completing tasks, sleep issues and other symptoms of the disorder, his mother said in a letter to the court.

They sent him to a Christian summer camp in 2006 and 2007, hoping the nature-centric programming would help him. But things got worse for March.

His mother wrote that in the following years, she and her husband sent him to a wilderness camp for troubled teens, addiction treatment, a boarding school and therapy.

“By this time, we were very confused and at a loss,” she wrote about that time.

A stabbing and domestic violence

In 2016, March got into an argument with a man at his parents’ Hyde Park home and stabbed him in the chest. Customs and Border Protection officer David Emberton mentioned the stabbing during a detention hearing days after the FBI raided Perrin March V’s home.

Emberton was assigned to an FBI joint terrorism task force at the time of the hearing.

“So he was held in jail until, kind of, the victim got out of the woods, so to speak, from chances of passing away,” Emberton said.

He said it was his understanding that any charges related to the stabbing were expunged, as were other previous instances of drug-related charges.

Diane March wrote that her son was convicted of a misdemeanor for the stabbing and served time in jail.

Samuel Heller, a Hamilton County public defender, told The Enquirer it’s not uncommon for the records of some assaults to be sealed and expunged. But a misdemeanor charge for such a seemingly violent crime seems unusual.

“If someone causes an injury while using a potentially deadly weapon like a knife, that action could certainly be looked at as a felonious assault, which is far more serious than a misdemeanor assault,” he said.

Without more information about the attack, it’s not possible to know why March faced a misdemeanor charge or if he received unusual treatment from the courts.

When contacted by The Enquirer, the Cincinnati Police Department and Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office said they did not have documents related to the stabbing.

‘A few rounds in her … stomach’

In 2021, March stalked and threatened to murder his pregnant girlfriend during a custody dispute.

In text messages to a friend, he said he’d “kill her and then myself,” and that “no ones (sic) taking my kid from me but me.” He threatened to put “a few rounds in her f—ing stomach.”

March was convicted of harassing communications later that year. Part of his sentence included a domestic violence order that barred him from possessing a gun, among other restrictions.

March later wrote on Telegram, an encrypted messaging service: “Due to a certain charge im not ‘legally allowed to possess fire arms’ for another 3 years … but also i wasn’t required to claim ownership of any or to turn any in to anyone. Laws are weird and vague sometimes here.”

‘Pale Face’ on an encrypted chat app

He used Telegram to communicate with people about his hateful views and violent thoughts.

He went by the alias “Pale Face” on a Telegram channel called Black DC’s Hate Crime Time.

It’s where he posted and chatted about his desire to kill people who are Jewish, nonwhite, LGBTQ and those he deemed to be “race traitors.” He encouraged others to also commit similarly motivated acts of violence.

And it’s where he wrote about his “dream death.”

The domestic violence order set him up to serve jail time for illegally possessing a firearm after the FBI executed a search warrant at his Northern Kentucky home May 13, 2022.

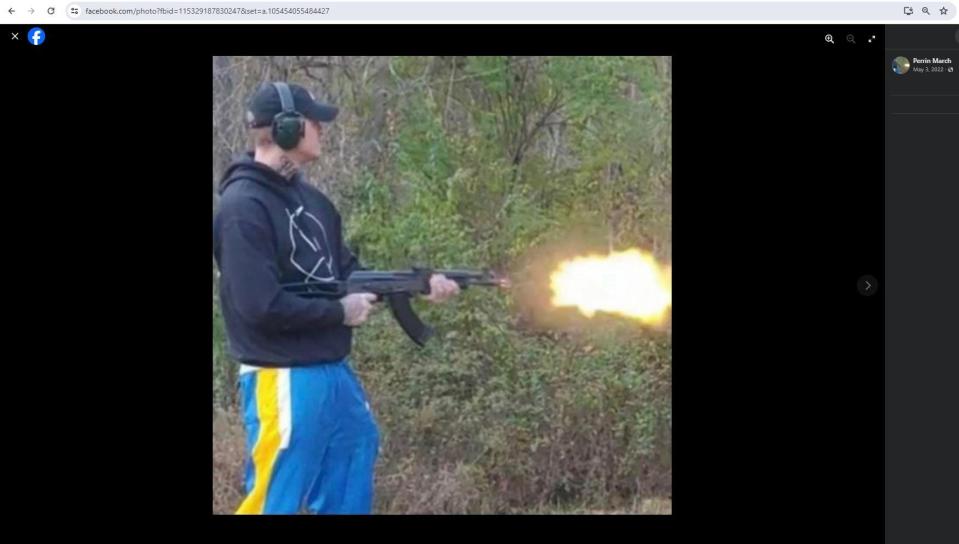

There, the FBI found an AK-47 pistol, 400 rounds of ammunition, a bullet with “white power” written on it and materials that can be used to make bombs. March also told an officer he had an AR rifle, a shotgun, and perhaps a .22-caliber rifle stored at his parents’ house.

How Falling Creek Camp changed Perrin March V’s life

In 2007, Perrin March V told his parents he wanted to come home early from his second stay at Falling Creek Camp, a nondenominational Christian summer camp near Tuxedo, North Carolina.

“We told him to stay bc we thought he would regret ‘giving up,’ ” his mother wrote to the court.

When he came back from camp, he was different.

“For the next several years, we had behavioral issues with Perrin that we couldn’t explain, and we had no idea how to address them,” his dad told the court in a letter.

They sent March back to the camp in 2008. He was kicked out and his mental state continued to decline.

His mother said he spiraled downward for the rest of his teenage years.

March threatened suicide multiple times, spent time in substance abuse treatment programs, was shipped off to a therapeutic teen wilderness program in Utah, and got sent to a therapeutic boarding school to finish his education.

He’d been using heroin since he was 12 or 13, his former attorney, Edward Metzger, wrote in a sentencing memorandum. He also added March has been diagnosed with PTSD, bipolar disorder and other mental health issues.

Years later, during a tearful phone call, he told his parents he was sexually abused at the camp.

“Imagine now knowing that you sent your son back for another year because you had no idea,” March’s father wrote to the court. “No wonder he found a way to get out.”

Court documents included news articles about former camp counselor Paul Clifton Canally, a man who was convicted of more than three dozen felonies involving sex crimes against minors and abusing boys who attended a school where he was a science teacher, according to March’s parents and other news reporting.

Canally was sentenced to roughly 50 to 60 years in prison.

The documents also include a letter Falling Creek Camp sent to parents in 2012 confirming Canally worked at the camp in the summer of 2007 – the year March asked his parents to pick him up early.

“I have never felt guilt, anger, sadness, shame, and grief like that before,” Diane March wrote.

Why wasn’t March V charged with other crimes?

Online posts about wanting to bomb a synagogue, allegedly testing homemade bombs and calling for the general death of people are often considered protected free speech, said H. Louis Sirkin, a Cincinnati attorney who specializes in First Amendment cases.

He reviewed some of the court documents in March’s case at The Enquirer’s request.

“It’s an evil thought, but you don’t punish somebody for an evil thought. I think you’ve got to have the evil thought and then you’ve got to make a movement, a substantial movement, in the course of committing that evil thought,” said Sirkin, who is Jewish.

If prosecutors had taken March to court on terrorism-related charges, for instance, it would have been difficult for them to prove he intended to follow through with his threats, Sirkin said. An argument could be made that March was just blowing off steam or joking online and never intended to commit the crimes, which is the argument his former attorney made in court.

It’s more concrete to charge March with illegal possession of a firearm and have the circumstances of his arrest considered during sentencing.

Prosecutors on the case, Assistant U.S. Attorneys Emily Greenfield and Andrew Boone, told The Enquirer in an email they cannot comment on the case aside from what’s already public record.

Mark Pitcavage, senior research fellow with the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, said March’s charge is common. He has studied extremism for more than 30 years.

“There are a lot of (white extremism cases) where there may have been other potential crimes … perhaps a plot or something like that, but they’re actually just prosecuted on weapons-related crimes, simply because those are so much easier to prove,” he said.

Why do young men fall into the ‘alt-right’ pipeline?

Ideas espoused by Perrin March V are common in cases of convicted extremists.

Mass shooters who’ve killed people – in Buffalo, New York; Christchurch, New Zealand; El Paso, Texas; Oxford, Michigan, among other places – have displayed Nazi and neo-Nazi symbols at their homes, on their guns and on their clothing. Some have white supremacy tattoos and others have live-streamed their massacres.

Online algorithms target people with more and more content of what someone is already interested in, said Heidi Beirich, co-founder and chief strategy officer at the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism.

“You don’t get shown a diversity of views, and you end up in a curated world where everything you see is hate,” she said.

Hate groups use those algorithms to recruit young white men, who’ve been called “foot soldiers of the movement,” said Paul Becker, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Dayton and extremism expert.

Becker said antisemitic and racist sentiments have moved from the fringe to mainstream in the past few years as political figures and pundits repeat them.

A conspiracy theory called the Great Replacement Theory, for example, refers to the fabricated notion that unspecified elites are attempting to replace the white populations of their countries with nonwhite immigrants.

Beirich said, “If you’re just a 16-year-old white kid, and you didn’t know anything about anything, you might look it up.”

How did March become radicalized?

Pitcavage said it can be difficult to pinpoint exactly how a person becomes radicalized, and that includes March.

“I’ve seen so many different ways that people have radicalized … that it’s really difficult to generalize and I would hesitate to speculate here,” he said.

Diane March, wrote a letter to the court in which she shared a text message she attributes to her son, explaining some of his experiences.

Perrin March V said he lived with all-consuming trauma after what happened to him at Falling Creek Camp in summer 2007. It led him to being untrusting, aggressive and suicidal.

“The second I found out drugs made the pain go away and the terror to stop, I decided they had to come first if I was going to survive,” he said in the text.

Over the years, nearly all his friends were ones he made while he was addicted to and buying drugs.

He was reportedly sober at the time of his arrest, but he said he learned “prejudices” from associating with those kinds of people.

“There’s still a lot I have to learn and unlearn,” he said. “But I’ve made a lot of serious progress but still have a lot to keep healing from.”

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Perrin March V: The Cincinnati antisemitic attack that didn’t happen

Source Agencies