The $843 million spacecraft SpaceX is designing to bring down the International Space Station at the end of the decade will be a super-powered version of its Dragon capsule that’s used to transport astronauts and cargo to orbit today, the company revealed Wednesday.

NASA awarded SpaceX the massive contract to develop the U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) last month. It won the award — over the only other bidder, Northrop Grumman — in part because the design leverages so much flight-proven hardware, NASA said in a source selection statement published Tuesday.

NASA was looking for proposals that maximized the use of flight heritage because reliability will be key, Dana Weigel, NASA’s ISS program manager, said during a Wednesday press conference. But even with the significant incorporation of the Dragon architecture, around half of the USDV will be entirely new, and 100% of the deorbit functionality will be new to this spacecraft, she said.

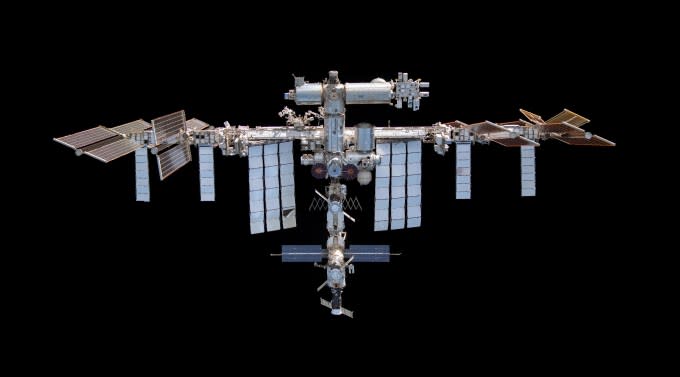

The USDV’s purpose is to execute a series of critical burns that will take place over the last week of the station’s life, but NASA is planning to launch the spacecraft around 18 months before these burns will take place. It will dock to the forward port of the ISS, where it will remain while the ISS slowly “drifts down” to Earth, Weigel said. The agency will leave crew onboard for as long as possible to maintain the station’s trajectory, but they’ll eventually depart for the final time around six months before reentry.

The USDV will come into play when the station reaches an altitude of around 220 kilometers above Earth. It will perform a series of burns to set the station up for a precise deorbit trajectory over a period of around four days before conducting the final reentry burn. The parts of the station that don’t burn up in Earth’s atmosphere will land in a yet-to-be-determined part of uninhabited ocean. This is the same disposal method the station has used for other large spacecraft, like Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus or Japan’s HTV cargo capsule.

The mission is complex, and SpaceX will have to develop a vehicle powerful enough to guide the station through increasing amounts of atmospheric drag. As Sarah Walker, SpaceX’s director of Dragon mission management, explained, “The thing that I think is most complex and challenging is that this [final] burn must be powerful enough to fly the entire space station, all the while resisting the torques and forces caused by increasing atmospheric drag on the space station to ensure that it ultimately terminates in the intended location.”

SpaceX’s ultimate design is a spacecraft that will have six times as much usable propellant onboard and three to four times the power generation and storage of Dragon capsules. The end result, at least according to a render released by SpaceX earlier Wednesday, is what looks like a conventional Dragon with a massive trunk attached to its end.

That trunk will house all that extra propellant, power generation and avionics needed to complete the mission, Walker said. That includes 30 additional Draco thrusters, in addition to the 16 already on the standard capsule configuration. A massive final burn is to help ensure that the debris footprint is small — and there will likely be some debris, ranging from the size of microwave ovens to small sedans.

NASA officials said the agency jointly agreed with the other station partners — Roscosmos, the European Space Agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and the Canadian Space Agency — to solicit a deorbit vehicle from private industry after realizing that Roscosmos-provided capabilities weren’t up to the size of the station. NASA released a request for proposals last fall.

The award is coming now because spacecraft of this complexity can take years to develop, Weigel said.

But the contract is different than SpaceX’s other big wins for NASA. Unlike its station crew and cargo transportation contracts, in which NASA simply purchases services for vehicles that SpaceX owns and operates, the deorbit vehicle contract flips this on its head: SpaceX will design and deliver the vehicle to NASA, but it will be the space agency’s responsibility to procure launch, operate the spacecraft and actually bring the ISS back to Earth.

The agency will start the rocket procurement process around three years prior to launch in a separate solicitation. Provided that ISS operations cease in 2030, the station would splash down sometime the following year.

Agency officials said they were keen to ensure an overlap with commercial space station providers in low Earth orbit, though they admitted that any number of variables could get in the way of a seamless transition. That includes the development schedules of the handful of commercial companies that have stations under development, like Axiom Space, the Voyager Space-led Starlab or the Blue Origin and Sierra Space venture Orbital Reef. Right now, NASA is cleared to operate the station through 2030; beyond that date, it would need to seek approval from government and cooperation with the other partner space agencies, said NASA associate administrator Ken Bowersox.

Source Agencies