When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

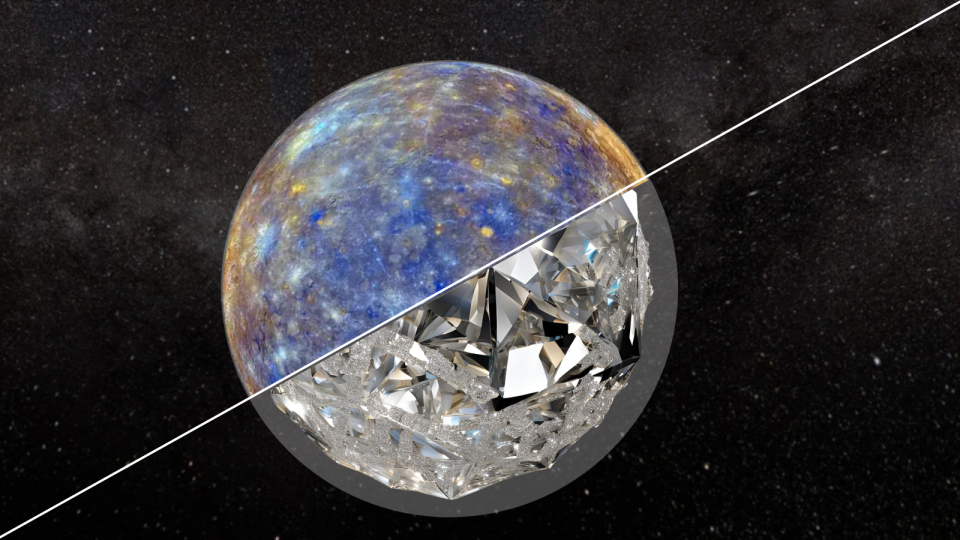

The solar system’s tiniest planet may be hiding a big secret. Using data from NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, scientists have determined that a 10-mile-thick diamond mantle may lie beneath the crust of Mercury, the closest planet to the sun.

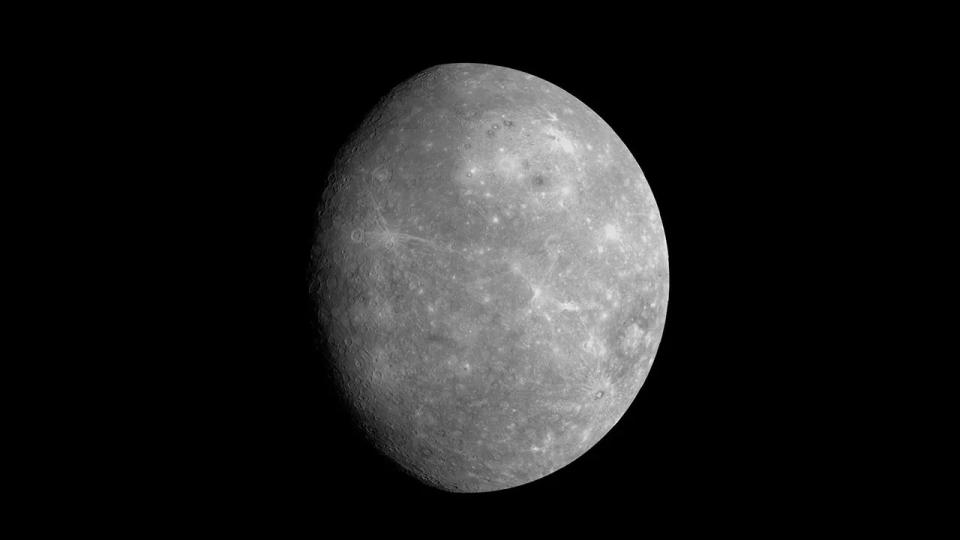

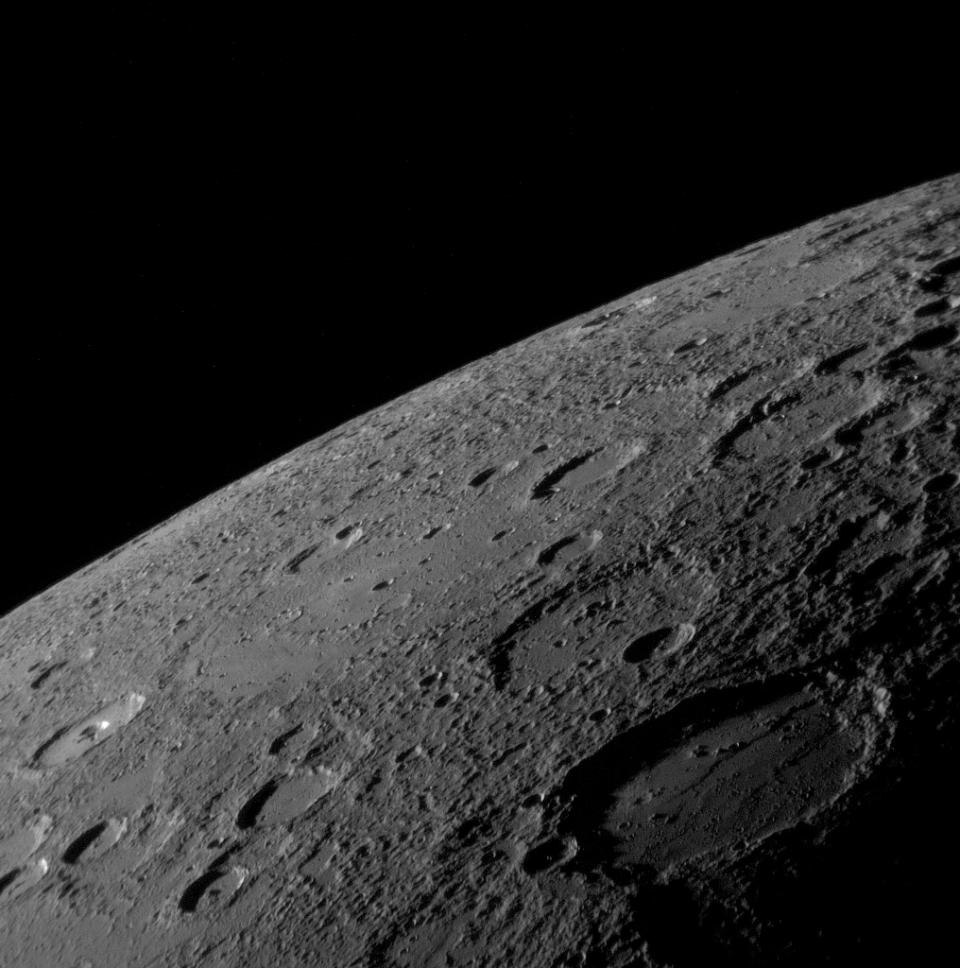

Mercury has long puzzled scientists as it possesses many qualities that aren’t common to other solar system planets. These include its very dark surface, remarkably dense core, and the premature end of Mercury’s volcanic era.

Also among these puzzles are patches of graphite, a type (or “allotrope”) of carbon on the surface of the innermost planet of the solar system. These patches have led scientists to suggest that in Mercury’s early history, the tiny planet had a carbon-rich magma ocean. This ocean would have floated to the surface, creating graphite patches and the dark-shaded hue of Mercury’s surface.

The same process would have also led to the formation of a carbon-rich mantle beneath the surface. The team behind these findings thinks that this mantle isn’t graphene, as previously suspected, but is composed of another much more precious allotrope of carbon: diamond.

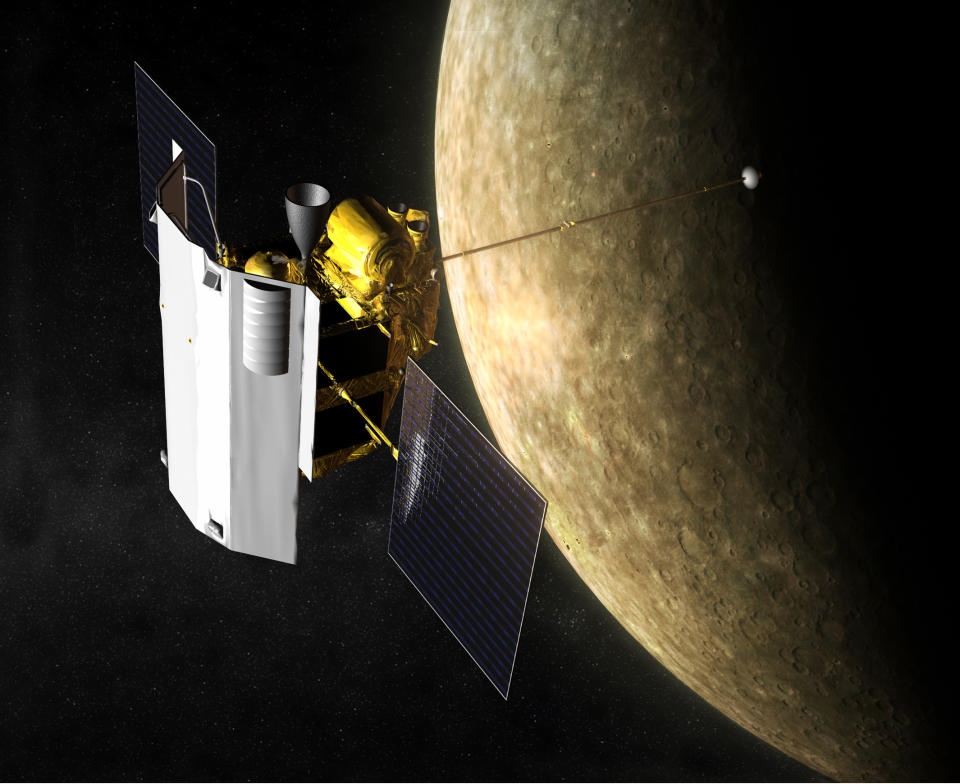

“We calculate that, given the new estimate of the pressure at the mantle-core boundary, and knowing that Mercury is a carbon-rich planet, the carbon-bearing mineral that would form at the interface between mantle and core is diamond and not graphite,” team member Olivier Namur, an associate professor at KU Leuven, told Space.com. “Our study uses geophysical data collected by the NASA MESSENGER spacecraft.”

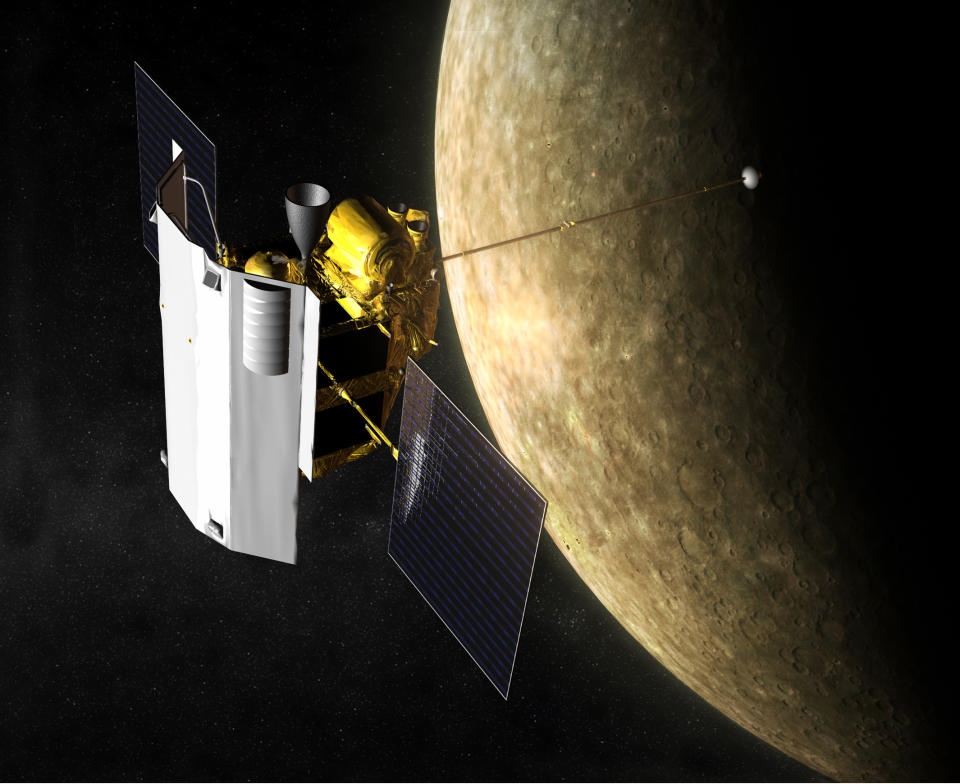

MESSENGER (Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging) launched in Aug. 2004 and became the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury. The mission, which ended in 2015, mapped the entire tiny world, discovering abundant water ice in shadows at the poles and gathering crucial data about Mercury’s geology and magnetic field.

Related: Mercury was shrinking for at least 3 billion years — and it still might be today

Under pressure!

This new study also relates to a major surprise that came a few years ago when scientists re-evaluated the distribution of mass on Mercury, discovering the mantle of this tiny planet is thicker than previously thought.

“We directly thought that this must have a huge implication for the speciation [the distribution of an element or an allotrope amongst chemical species in a system] of carbon, diamond vs graphite, on Mercury,” Namur said.

The team investigated this here on Earth by using a large-volume press to replicate the pressures and temperatures that exist within the interior of Mercury. They applied incredible amounts of pressure, over seven gigapascals, to a synthetic silicate acting as a proxy for the material found in the mantle of Mercury, achieving temperatures of up to 3,950 degrees Fahrenheit (2,177 degrees Celsius).

This allowed them to study how minerals like those that would have been found in Mercury’s mantle in its early existence changed under these conditions. They also used computer modeling to assess data about Mercury’s interior, which gave them clues to how the diamond mantle of Mercury could have been created.

“We believe that diamond could have been formed by two processes. First is the crystallization of the magma ocean, but this process likely contributed to forming only a very thin diamond layer at the core/mantle interface,” Namur explained. “Secondly, and most importantly, the crystallization of the metal core of Mercury.”

Namur said that when Mercury formed around 4.5 billion years ago, the core of the planet was fully liquid, progressively crystallizing over time. The exact nature of the solid phases forming in the inner core is not currently well known, but the team believes that these phases must have been low in carbon or “carbon-poor.”

“The liquid core before crystallization contained some carbon; crystallization, therefore, leads to carbon enrichment in the residual melt,” he continued. “At some point, a solubility threshold is reached, meaning the liquid cannot dissolve more carbon, and diamond forms.”

Diamond is a dense mineral but not as dense as metal, meaning that during this process, it would have floated to the top of the core, stopping at the boundary of Mercury’s core and its mantle. This would have resulted in the formation of an around 0.62-mile (1 km) thick diamond layer that then continued to grow over time.

The discovery highlights the differences between the birth of the closest planet to the sun when compared with the creation of the solar system’s other rocky planets, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

“Mercury formed much closer to the sun, likely from a carbon-rich cloud of dust. As a consequence, Mercury contains less oxygen and more carbon than other planets, which led to the formation of a diamond layer,” Namur added. “However, Earth’s core also contains carbon, and diamond formation in the Earth’s core has already been suggested by various researchers.”

The researcher hopes that this discovery could help reveal clues to some of the other mysteries surrounding the solar system’s smallest planet, including why its volcanic phase was cut short around 3.5 billion years ago.

“A major question that I have about Mercury’s evolution is why the major phase of volcanism lasted only a few hundred million years, much shorter than other rocky planets. This must mean that the planet cooled down very fast,” Namur said. “This is partly related to the small size of the planet, but we are now working with physicists to try to understand if a diamond layer could have contributed to very fast heat removal, therefore terminating major volcanism very early.”

RELATED STORIES:

— Why is Mercury so weird? Blame the giant outer planets.

— European probe captures stunning up-close views of planet Mercury during brief flyby (video, photos)

— See Mercury’s giant, comet-like tail in stunning new image as it passes close to the sun

Namur said that the team’s next step will be to investigate the thermal effect of a diamond layer at the mantle/core boundary. This study could be supported by data from a mission that will follow in the footsteps of MESSENGER.

“We are also eagerly waiting for the first data collected by BepiColombo, hopefully in 2026, to refine our understanding of Mercury’s internal structure and evolution,” Namur concluded.

The team’s research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source Agencies