When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

Water is life, at least as we know it. Every life form on Earth uses liquid water, and researchers who study the origin of life believe life’s complex chemistry likely got started either in a warm pool on Earth’s surface or close to a deep-sea ocean vent.

Therefore, planetary scientists are particularly interested in extraterrestrial places with liquid water.

While Earth has liquid oceans on its surface, only 0.2% of Earth’s mass is water. By contrast, some planets and moons may be up to 50% water, meaning they could have oceans hundreds, or even thousands, of miles deep.

Let’s dive into some of the most promising water worlds in the solar system and beyond.

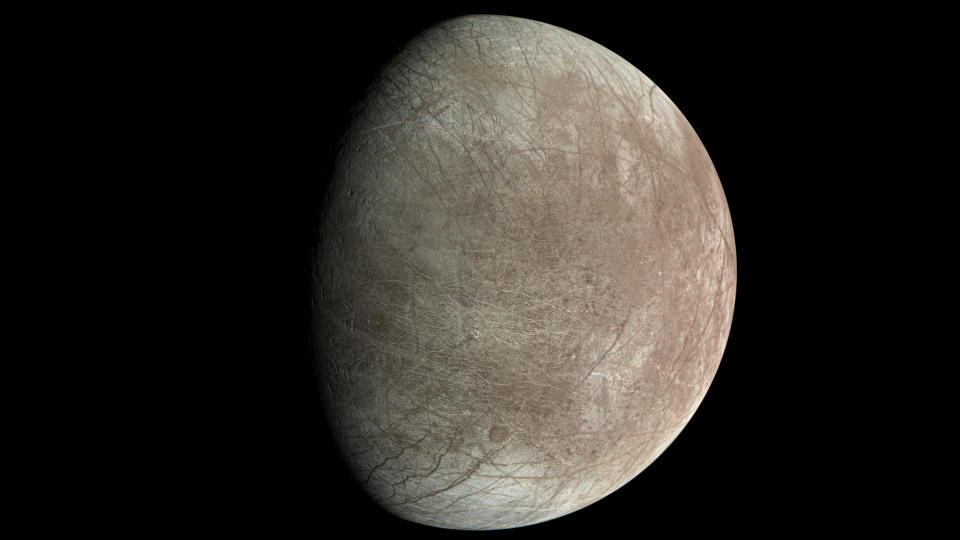

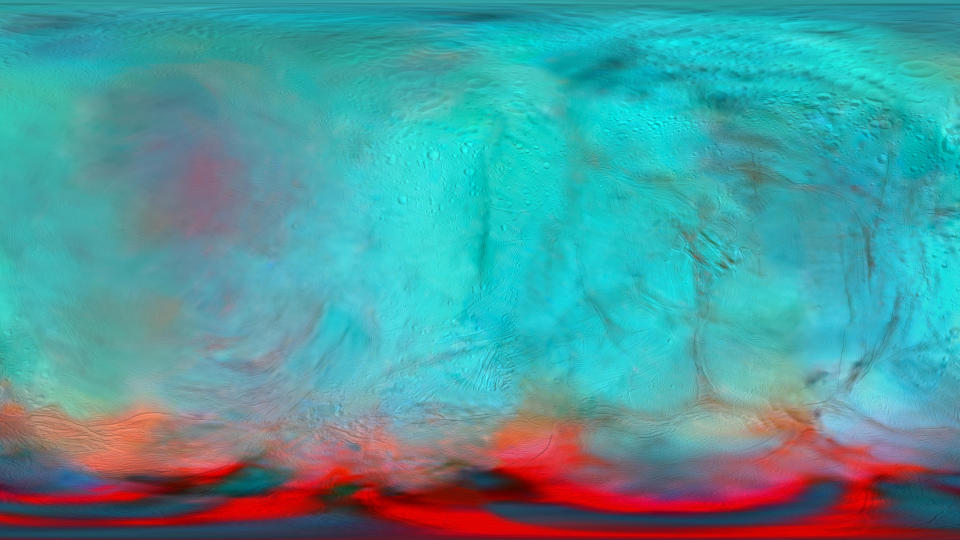

Europa

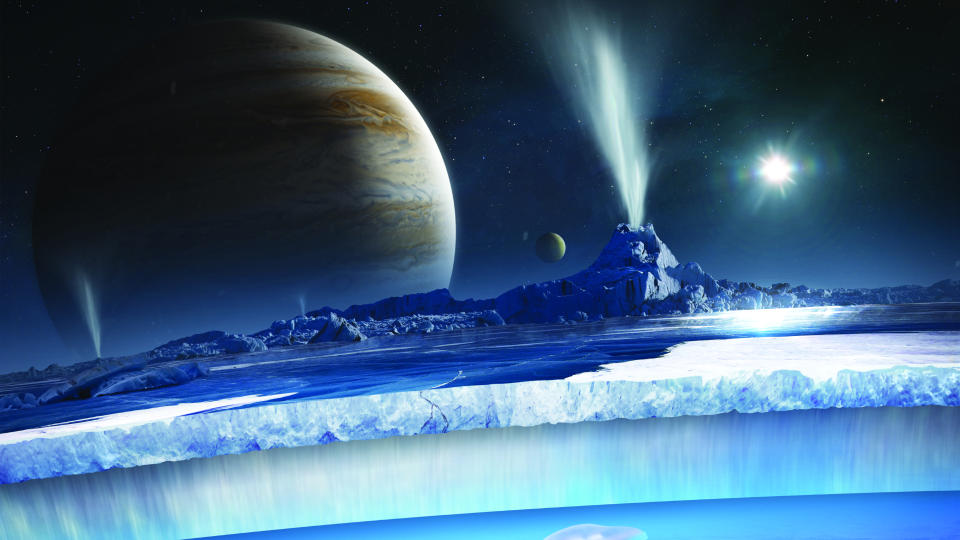

Scientists first became aware that Jupiter’s moon Europa likely possessed a liquid ocean underneath its icy exterior during NASA’s Galileo mission, which launched in 1989. For nearly eight years, the Galileo spacecraft orbited Jupiter, where it observed interactions between Europa and Jupiter’s magnetic field that indicated the presence of water inside the moon.

The Europa Clipper mission will travel to Europa to determine if it is habitable. It is the first time a spacecraft will travel to a water world. Researchers are particularly interested in the mixing of water and rock deep inside Europa’s interior, where nutrients and chemicals may be able to support microbial life similar to the way ocean vent sites host life on Earth.

Callisto

Callisto, Jupiter’s second-largest moon, could also be home to a subsurface liquid ocean. Callisto has the most-cratered surface in the solar system, suggesting that the moon does not have any geological or weathering processes. However, roughly 155 miles (250 kilometers) beneath the surface, a salty ocean may be interacting with a layer of rocks, which could facilitate habitable conditions deep inside the moon. Oxygen has also been detected in Callisto’s exosphere, the uppermost region of the moon’s thin atmosphere.

Ganymede

In 2015, scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope found that Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede, also likely possessed an interior liquid-water ocean. Ganymede has its own magnetic field, which generates auroras at its magnetic poles. Observations of Ganymede’s auroras showed that an interior ocean of liquid water likely suppresses the rocking of Ganymede’s magnetic field as it interacts with Jupiter’s magnetic field.

Ganymede’s ocean is thought to be 60 miles (100 km) thick, which is nearly 10 times deeper than Earth’s ocean. Ganymede and the other Galilean moons likely formed from similar materials that surrounded Jupiter during the early stages of the solar system, which explains why each moon likely has a relatively high ratio of water.

Enceladus

Enceladus — a small, icy moon of Saturn — is one of the most exciting places where planetary scientists have detected water in the solar system. This is because ice geysers on Enceladus’ surface spew water and ice into space, providing a way for researchers to directly sample materials from the moon’s interior.

This water and ice are ejected from an interior ocean, and in 2005, the Cassini spacecraft discovered that these materials gushed from the moon’s surface at roughly 800 mph (1,300 km/h). Warm vents are also thought to provide the moon’s ocean with minerals and nutrients that are crucial to life.

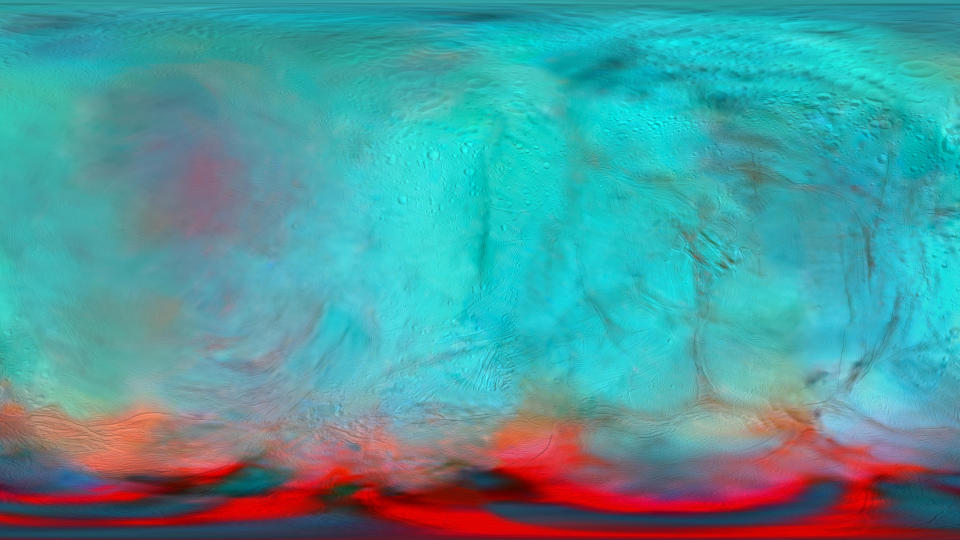

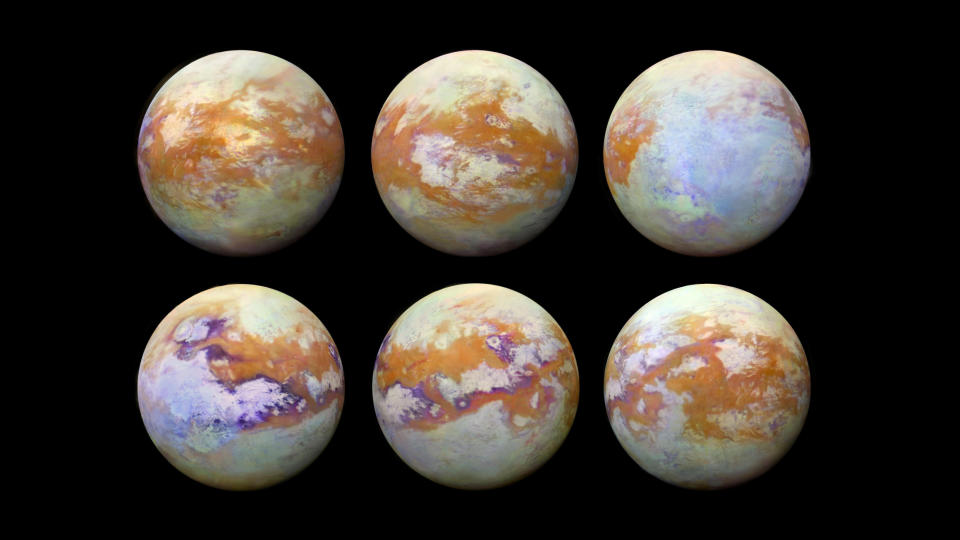

Titan

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is unlike anything else in the solar system. Its surface is covered in lakes, rivers, seas, clouds and rain composed of the hydrocarbons methane and ethane. Beneath its icy crust, Titan is thought to house an internal liquid-water ocean, which could be home to life. Its surface could also host life forms that are completely different from anything on Earth, as they might use different chemical pathways to generate energy.

Although Titan’s chemical composition is very different from Earth’s, this large moon has features associated with habitability, such as a dense atmosphere and dynamic geological and weathering processes.

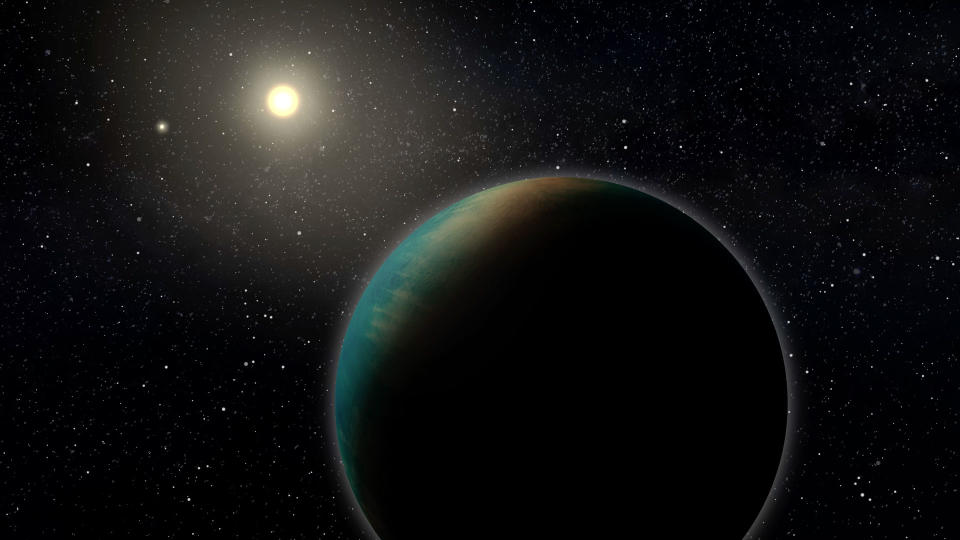

TOI-1452 b

In 2022, using data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, an international team of researchers discovered the exoplanet TOI-1452 b. The planet is about 1.6 times the size of Earth and is classified as a super-Earth. It is five times as massive as Earth, and its density may suggest that a large percentage of the planet — potentially 30% — is composed of water.

TOI-1452 b, which is about 100 light-years from Earth, is a prime candidate for further observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

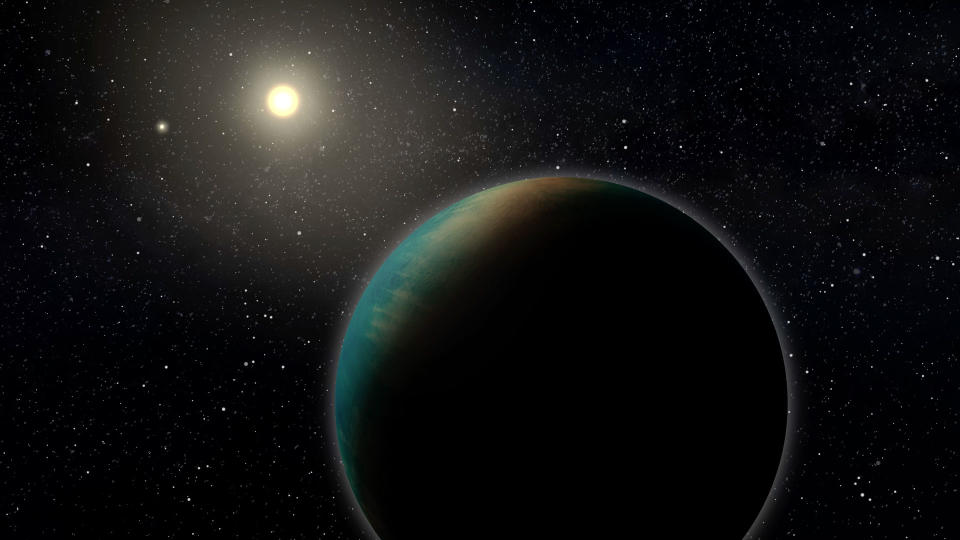

LHS-1140 b

In July 2024, researchers using the JWST observed an atmosphere on the exoplanet LHS-1140 b, which may sustain a liquid ocean on its surface. The planet orbits a red dwarf star five times smaller than the sun and sits 48 light-years from Earth.

Further JWST data suggested the planet could be composed of 10% to 20% liquid water. LHS-1140 b orbits in such a way that the same side always faces its star. Additionally, current models have suggested the planet could be a giant snowball, which means there could be a “bull’s-eye” ocean on the side that always faces its star.

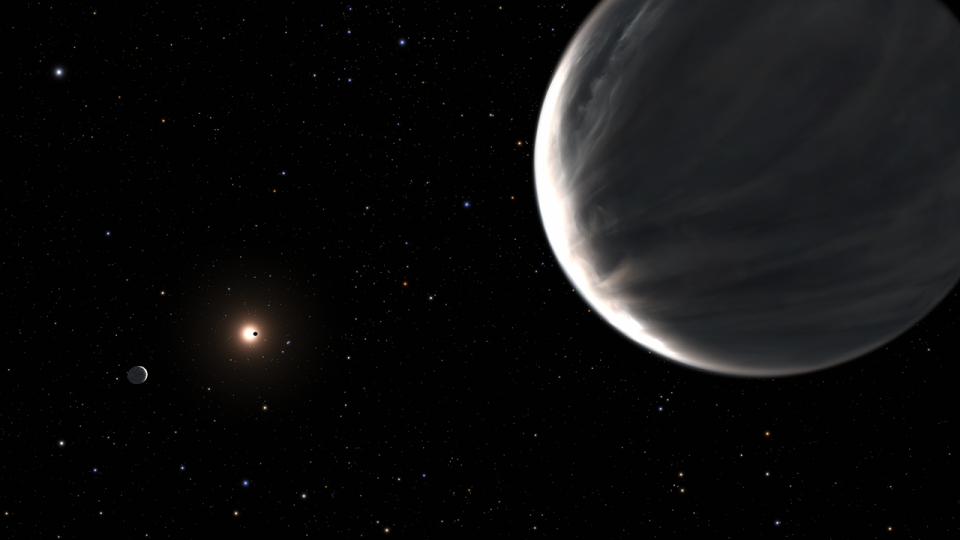

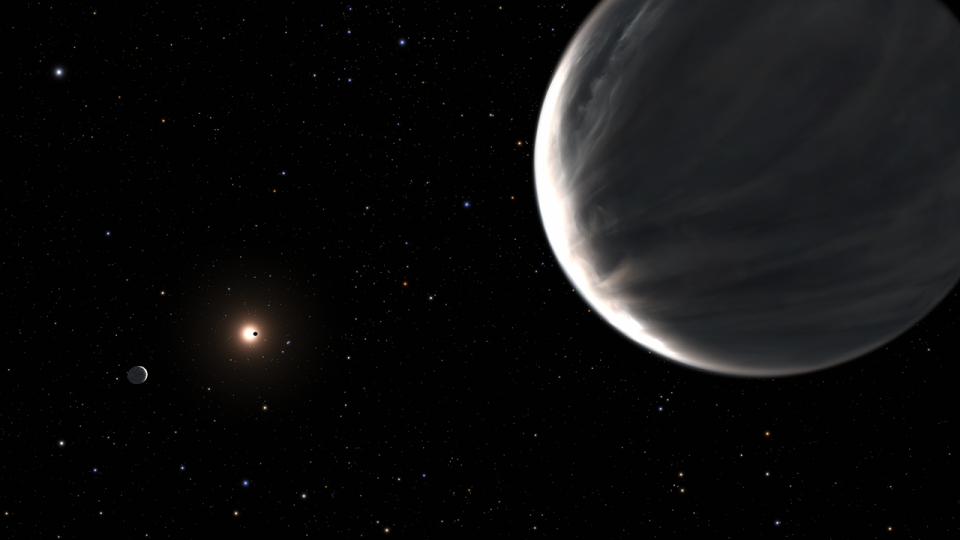

Kepler-138 c and d

Two possible water worlds, Kepler-138 c and Kepler-138 d, orbit a red dwarf star 218 light-years from our solar system. In 2022, researchers found that the planets’ apparent densities suggested that these worlds may be composed of a high percentage of water.

Researchers think up to half of the materials that make up these planets should be lighter than rock but heavier than hydrogen or helium. The most common ingredient in the cosmos that fits these criteria is water.

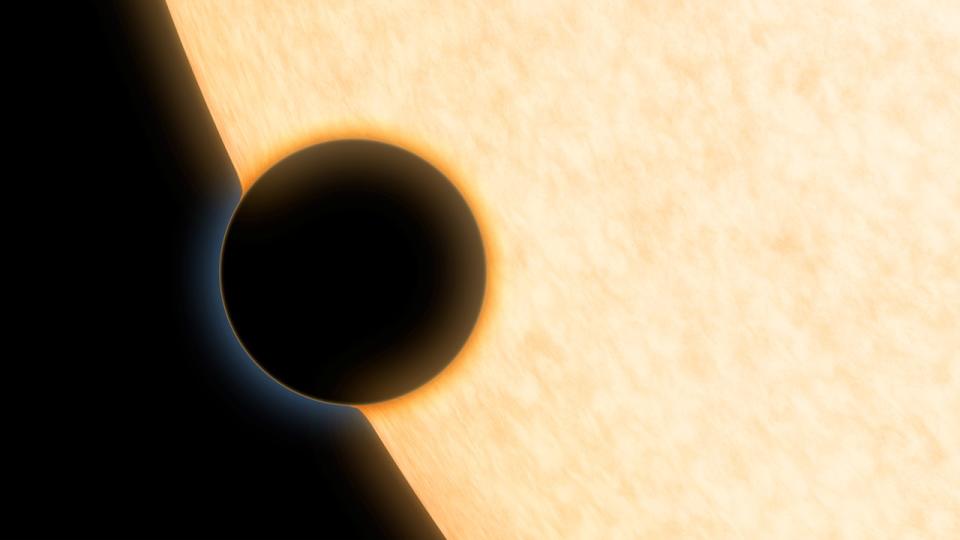

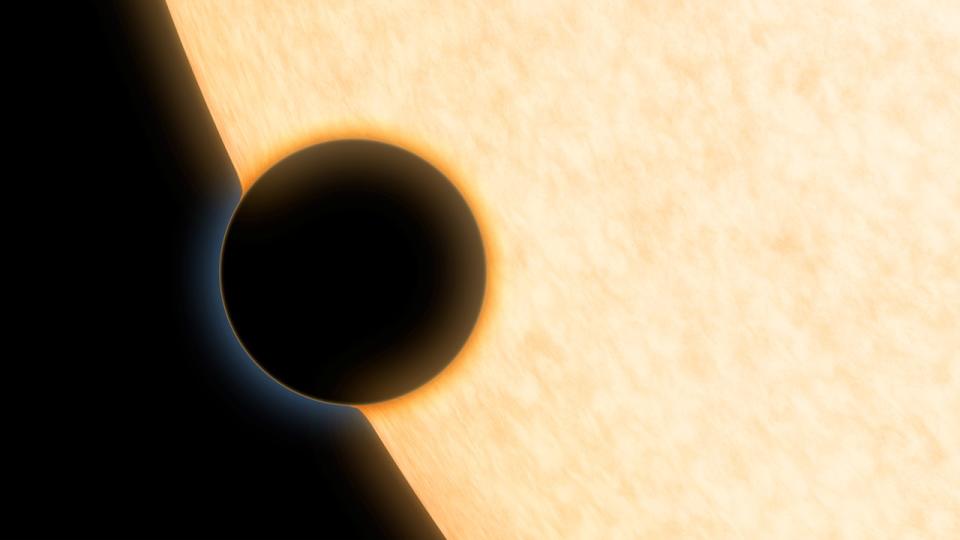

HAT-P-11 b

In 2014, astronomers discovered water vapor on a Neptune-size world 124 light-years from Earth. The exoplanet, designated HAT-P-11 b, is close to its home star, taking only five days to make a full orbit. It is a scorching world, with surface temperatures that soar to over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (530 degrees Celsius), and is believed to house a rocky core and a gaseous, water-vapor atmosphere rich in hydrogen.

Researchers spotted water in HAT-P-11 b’s atmosphere using a method called transmission spectroscopy. When an exoplanet passes by — from our point of view — its host star, the starlight travels through the exoplanet’s atmosphere. Different atmospheric particles absorb some of the starlight at specific wavelengths. By analyzing which wavelengths are absorbed, scientists can determine the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

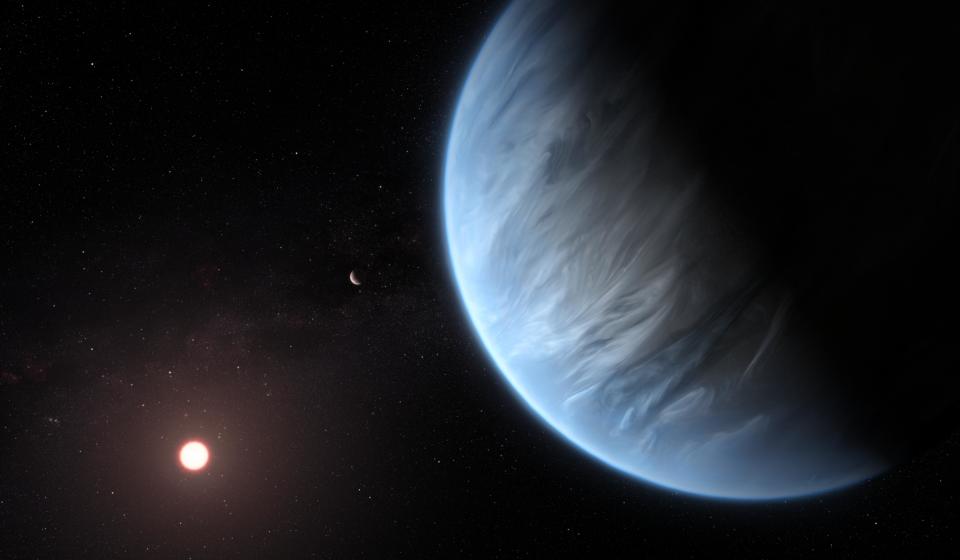

K2-18 b

In 2019, water vapor was discovered in the atmosphere of a planet called K2-18 b, a super-Earth 110 light-years from the solar system. The exoplanet orbits a red dwarf star and is thought to be just the right distance from it for any water on its surface to exist in liquid form.

However, planetary scientists are unsure if the planet is a rocky world or a giant ball of liquid and gas.

Additional information

Based on current exoplanet data, super-Earths and sub-Neptunes are thought to be the most common planet classes in our galaxy, and a subsection of those planets are likely water worlds. These planets are big, however, and the interaction of water in their oceans and rock in their interiors will dictate how habitable those planets might be. You can learn more about those dynamics in this research published in the journal Nature.

Europa Clipper will give scientists unprecedented information about the habitability of small water worlds, such as those found around Jupiter and Saturn. Read more about why the mission will visit Europa on the NASA mission page.

Water worlds are thought to be common in the cosmos, which means they may be some of the best places to look for extraterrestrial life. For a discussion on how common they might be, read this paper in the journal Science.

Bibliography

Callisto, NASA [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://science.nasa.gov/jupiter/moons/callisto/facts/]

Discovery Alert: Intriguing New ‘Super-Earth’ Could Get a Closer Look, NASA [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://science.nasa.gov/universe/exoplanets/discovery-alert-intriguing-new-super-earth-could-get-a-closer-look/]

Europa Clipper, NASA [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://europa.nasa.gov/]

Enceladus, NASA, [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://science.nasa.gov/saturn/moons/enceladus/]

Ganymede: Facts, NASA [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://science.nasa.gov/jupiter/moons/ganymede/facts/#hds-sidebar-nav-4]

Kovačević, T., González-Cataldo, F., Stewart, S.T. et al. Miscibility of rock and ice in the interiors of water worlds. Sci Rep 12, 13055 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16816-w

Martin, W., Baross, J., Kelley, D. et al. Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nat Rev Microbiol 6, 805–814 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1991

NASA’s Hubble Observations Suggest Underground Ocean on Jupiter’s Largest Moon, NASA [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble-space-telescope/nasas-hubble-observations-suggest-underground-ocean-on-jupiters-largest-moon/]

NASA Telescopes Find Clear Skies and Water Vapor on Exo-Neptune, NASA, [Accessed 7/19/2024] [https://hubblesite.org/contents/news-releases/2014/news-2014-42.html?Year=2014&news=true]

Piaulet, C., Benneke, B., Almenara, J.M. et al. Evidence for the volatile-rich composition of a 1.5-Earth-radius planet. Nat Astron 7, 206–222 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01835-4

Rafael Luque,Enric Pallé,Density, not radius, separates rocky and water-rich small planets orbiting M dwarf stars. Science 377,1211-1214(2022).DOI:10.1126/science.abl7164

Switek, B. Debate bubbles over the origin of life. Nature (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2012.10024

Titan, NASA, [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://science.nasa.gov/saturn/moons/titan/#h-more-to-explore]

Two Exoplanets May Be Mostly Water, NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer Find, NASA [Accessed 7/19/24] [https://hubblesite.org/contents/news-releases/2022/news-2022-048#section-id-2]

Source Agencies