BBC

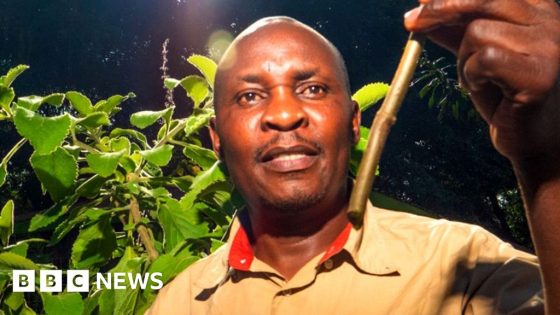

BBCMartin Odhiambo has always been interested in the healing properties of plants – and for years has been enthusiastically sharing that knowledge with fellow Kenyans.

Every Thursday at an amphitheatre at the Nairobi National Museum, he talks to dozens of people who have come to learn and exchange information about traditional medicine.

Despite worries over the efficacy and safety of these treatments, it is estimated that around 80% of people in African countries rely on them when they are ill, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

One way to allay safety concerns in Kenya would be for the authorities to find a way to oversee traditional medicine, as happens in some other countries.

But for now Mr Odhiambo is keen to let others know about plant remedies he believes can deal with common illnesses, such as colds, skin conditions and stomach upsets.

He argues that long before the onset of conventional medicine, there were traditional healers who knew from those before them what was good for treating which condition.

The information exists within communities, but does not really travel further.

Mr Odhiambo works for the Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health (Ticah), which has formed a partnership with the museum, seen as a repository of the country’s cultural heritage.

There he takes care of a special garden, known as a physic garden, which has more than 250 species of medicinal plants – they are not for sale but for education.

For years, Mr Odhiambo has studied medicinal plants – the scientific research as well as talking to the people who use them – soaking up so much folklore and indigenous knowledge that he says he now has “a tendency to dream about plants”.

At one of his Weekly Plant Talks, he sounds professorial, imparting his vast knowledge to all gathered – including herbalists, a midwife coming from the US, a psychologist, a teacher, a university student and a businesswoman.

The talk starts with a prayer and a recap of what was learnt the previous week, and then quickly moves on to the plants of the day.

The initial focus is on Lantana camara – a common shrub that has different local names including “nyabende” and “mukige”.

Traditionally, it is said to treat headaches as well as ease toothaches – and can act as an insect repellent. Plus its twigs can be used as a toothbrush .

It also brings “good vibes and creates positive energy”, a participant says.

As the meeting continues, people discuss, share and learn about a whole range of plant remedies for diverse health problems.

They also talk about the cultural contexts in which the plants are used such as in traditional rites, food preservation or even their mystic powers that instil “goodwill” within a community.

This forum is not used to discuss scientific research and whether the claims can be proven in a controlled experiment.

“We do not validate this information,” says Vitalis Ochieng, Ticah’s senior programme manager, emphasising that the point is for people to share what they know.

The organisation’s key mandate is to show the value of traditional medicine and amplify the voices of those who practice it, he adds.

One of the things hampering the wider adoption of traditional medicine in Kenya is that there is no government policy encouraging its safe use.

Mr Ochieng argues that indigenous knowledge could be the basis for scientific research, adding that in countries like China, traditional medicine is accepted and even exported as “alternative medicine”.

He is campaigning for traditional medicines to be regulated and standardised in Kenya, legislation that has been in the works for several years.

At the moment so-called “herbal clinics”, many selling poor quality remedies, have given traditional medicine a bad name, something experts in the East African nation acknowledge.

There have been problems with fraudsters, as well as the deliberate or accidental contamination of the products, says Dr Ruth Nyangacha, the deputy director of Centre for Traditional Medicine Research (CTMDR) – a government agency that advises the health ministry on traditional medicine.

She tells the BBC this is especially risky for patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, as they often turn to these remedies, partly because of cost but also as they are easier to get hold of in remote areas.

At her first plant talk at the museum, businesswoman Joyce Ng’ang’a says she turned to traditional medicine as she found conventional medication had not helped her condition.

In fact the drugs she was prescribed after her diagnosis with chronic stomach acid reflux eight years ago had had side effects like making her forgetful.

Even a trip to India for treatment had not helped – which is why she says she sought out herbal remedies.

“I have never found a reason to go back to them,” she enthused, referring to the conventional medicine she has now abandoned.

It is a course of action that doctors would not recommend over safety concerns, but Ms Ng’ang’a says she hopes her experience will mean traditional herbal therapies will eventually become formalised.

Patrick Mwathi

Patrick MwathiHerbalist Patrick Mwathi attends the plant talks nearly every week – wanting to improve his craft. He has been practising for decades, learning first-hand from his father in the 1970s.

He develops and sells herbal products locally – some of which he shares with others at the lecture, including a “herbal tea” with packaging that says it can aid infertility. It can also “detox” and “activate” the kidney and “cleanse” the liver, he says.

Another product is said to treat depression.

Such treatments have not been scientifically proven to be effective and Ticah encourages herbalists to register and work with the authorities to formalise their remedies.

Mr Mwathi has taken samples to government laboratories for chemical analysis – and they have passed tests to show they are are effective and not harmful.

But the process required to get a product to market – including standardisation and quality control – is long and involves many government agencies. Like other traditional practitioners he lacks the time and money to do this.

Dr Nyangacha explains that some of the challenges include knowing when the active components of remedies expire – noting that it often comes down to “guesswork”.

The CTMDR, a unit of the government’s Kenya Medical Research Institute (Kemri), does not have the funding to get the herbal remedies they test for efficacy approved for conventional use.

But there is no reason it could not be done, Dr Nyangacha argues, pointing out that Kemri has developed its own products, including a herbal medicine used in the treatment of genital herpes and a salt that is used for hypertension.

“We have genuine ones and traditional medicine [that], I must say, works.”

Mr Odhiambo needs no convincing – in fact he hopes his passion for plants will show Kenyans that common illnesses can be treated without suspicion using remedies “like in the olden days”.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

Source Agencies