Disney

Disney“I may be super but I’m no hero.”

In Deadpool’s own words, he is “just a bad guy who gets paid” to mess with “worse guys”.

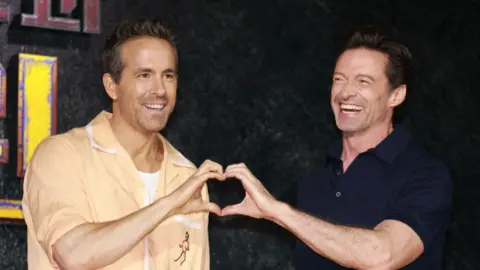

Ryan Reynolds’s character in Deadpool and Wolverine – the third edition of the Marvel series released this week – is far from the only antihero to have won over fans in recent years.

They are typically morally ambiguous characters that are neither a superhero nor a villain.

Take Wanda Maximoff (Scarlet Witch), who will do everything she can to create a family, including holding an entire community hostage in the 2021 show WandaVision.

And later this year, the villain-turned-antihero film Venom will return to the big screen a third time, as a journalist who tries to protect the innocent at all costs.

Deadpool, aka Wade Wilson, gains immortality after joining an experiment programme to cure his cancer, but things go wrong and he is left to die, leading him on a revenge-driven quest to kill his betrayers.

But what is it about these characters of murder and mayhem that connect with some people more than superheroes do?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to 26-year-old comics fan Chelsea-Lee Nolan from Kent, they are simply “more human”.

“Nobody is wholly good or wholly evil, so the idea of an antihero is quite nice,” she says.

It is in these grey areas that Ms Nolan can see “elements” of herself.

“I’m not overly perfect and I don’t aim to be,” she adds. “The idea of a hero who makes no mistakes is unrelatable.”

For writer and performer Reece Connolly, 30, who lives in London, antiheroes are simply more realistic.

“They move towards a moral right, but they make mistakes, they have regrets, bad habits and quirks of character,” Mr Connolly explains.

In the comic book Deadpool (2008), Issue 45, a group of trafficked women call him a “good man” after he rescues them, but the mercenary quickly rejects it, saying: “Well… okay, yeah – maybe sometimes parts of me are good but there are, like other parts of me that’re, umm…”

His reluctance to be called “good” is a recognition of his flaws.

The “Merc with a Mouth”, as Deadpool calls himself, is loud, murderous and maddening – everything a superhero isn’t.

Reece Connolly

Reece ConnollyOther antiheroes share similar traits. Loki, played by Tom Hiddleston, is a villain but has gradually become someone who tries to do the right thing, albeit with the trickster’s mischief thrown in.

The “dark side” that antiheroes embrace plays a huge role in their appeal, according to Dara Greenwood, of Vassar College in New York, who has spent time studying such characters.

“[They] give us the imaginative opportunity to lean into the ‘dark side’ of human behaviour in a way that is safe from repercussion or reproach,” the associate professor of psychological science says.

That might partly support the affective disposition theory – which suggests that entertainment is enjoyed more when a character that audiences like succeeds and a disliked character fails.

A defining part of Deadpool is his humour. He is known for his ability “to drop mad one-liner science”, as he calls it, wisecracks and innuendos – usually at the most inappropriate times.

Prof Greenwood says that when paired with humour, violence can come across as playful instead of toxic, which “desensitises us” to its brutality.

Disney

DisneyMany superheroes see their powers as a calling to do good – the likes of Spider-Man continue as fan favourites, showing resilience in the face of suffering and continuing to save, not harm people.

But Deadpool knows he is a fictional character who exists for the pleasure of others, and constantly breaks the fourth wall to talk to readers and viewers. A 2019 study shows that this rapport gives us the same feelings of attachment and intimacy we would get with a personal relationship.

Ms Nolan says it makes her feel “involved”, while Mr Connolly likens it to “a conversation, or a secret or in-joke we’re being let in on”.

To him, antiheroes like Deadpool are “heroes with all the interesting bits left in”

“The mess, the weirdness, the flaws,” he says.

Source Agencies