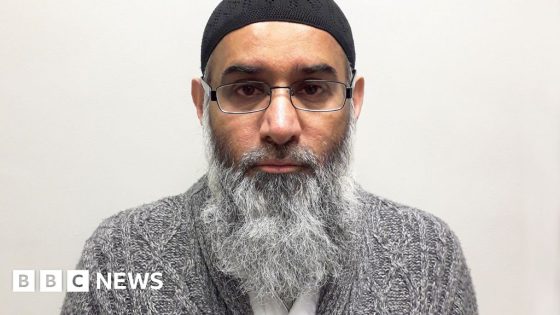

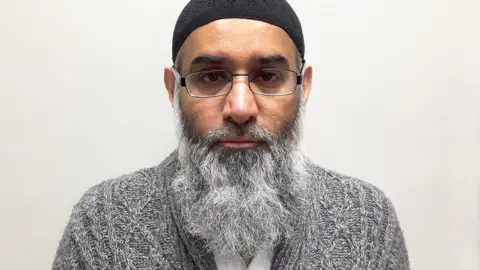

Metropolitan Police/PA Media

Metropolitan Police/PA MediaThe threat from international and domestic terror presents a “breadth of challenge greater than it has ever been”, according to senior US and UK police officers who oversaw the successful prosecution of Anjem Choudary.

The Islamist preacher from east London is starting a life sentence for directing a group banned under UK terror law, and encouraging support for it online.

The officers say his case highlights the continuing danger posed by radicalisers – and the violent groups they support.

But they also say counter-terrorism forces are now battling a wide diversity of threats – including from a worrying number of people who don’t support an underlying ideology, but are simply drawn to violence.

Young people being attracted to online extremism through conspiracy theories, the actions of “hostile states” such as Russia, and the “toxicity of our political environment” are also concerning, they warn.

Following Choudary’s trial, the BBC spoke exclusively to Matt Jukes, the UK’s head of counter-terrorism policing, and Rebecca Weiner, Deputy Commissioner of Intelligence and Counterterrorism at the New York Police Department.

They told us that alongside extremist groups energised by events in the Middle East, the new security threats were sparking multiple investigations.

It is a “palpably different picture than it was,” says Assistant Commissioner Jukes.

Deputy Commissioner Weiner singles out online extremism as probably the most important aspect of what she terms an “everything, everywhere, all-at-once threat environment”.

Suspects with ‘no settled view of the world’

With two wars – Israel-Gaza and Ukraine – being fought in what Ms Weiner calls “a tsunami of disinformation”, she says it is hard for people to understand what is true and what is not – “and that is playing out in the realm of violence”.

People are being “overwhelmed with false narratives” and fed conspiracy theories, she says.

A disturbing aspect of this, says Mr Jukes, is the increasing number of those turning to terrorism because of a fascination for violence, rather than ideological fanaticism.

He says in 20% of cases his officers now handle, terror suspects have no settled view of the world: “We are seeing people literally flip from searching for neo-Nazi material online to searching for Islamist material.”

This is a real shift, he says, with people having previously gone from a single ideology, to extremism, and on to violence.

Young people are viewing “dehumanising content”, including extreme pornography – says Mr Jukes – and being asked in online groups “to prove themselves by producing more and more extreme content”.

This includes terrorist material created using artificial intelligence, he says, with gaming being one of the “gateways” into extremism online.

The age profile of those drawn into this extreme environment is coming down – and he worries about “very young people who only need to take up a knife or use a vehicle as a weapon to carry out a deadly attack”.

Nearly one in five of those arrested as terror suspects in the UK in the past year were under 18.

Counter-terror police on both sides of the Atlantic have also been kept busy since last October’s attack by Hamas on Israel, in which about 1,200 people were killed and 251 taken hostage. More than 39,000 Palestinians have been killed, according to Gaza’s health ministry.

Fifty police investigations have been launched in the UK into support or encouragement of terrorism. There has also been a big increase in antisemitic and Islamophobic hate crime.

Government statistics for the year ending in March 2024 show terror-related arrests in the UK were up by 23% on the previous year (although they were lower than the period between 2013 to 2020).

‘Determined and shameless’ state actors

Five years ago, says Mr Jukes, he would have been kept awake primarily by fears of an IS attack in the UK, but now he says one of his main concerns would be the growing threat from “determined and shameless” state actors.

For many years, he says “hostile actions of states” formed only a very small part of police and MI5 investigations. But this has grown more than fourfold since the 2018 Salisbury poisonings, says Mr Jukes, when a nerve agent was used to try to assassinate a former Russian spy and his daughter.

The spy, who had defected to the West, and his daughter were badly injured – but a British woman died after coming into contact with Novichok. Russia has always denied involvement.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere has also been an increased threat from parts of the Chinese state, he adds, and at least 15 foiled plots by Iran in the past two years to either kidnap or kill those in the UK it considers enemies of the regime.

“If these authoritarian organs of the state feel like the UK or the US is fair [game] for them to pursue their adversities, then everything we stand for in terms of being a safe, liberal democracy is challenged,” says Mr Jukes.

The two police chiefs also point to “toxicity” in the political environment, which has led to politicians becoming targets of violence – including two British MPs murdered in terror attacks, and the failed assassination of Donald Trump at a campaign rally on 13 July.

I ask if there is any reassuring news amid this scary picture of dispersed danger.

People can “take a degree of comfort”, says Mr Jukes, that since the attacks in London and Manchester in 2017, “that terrible year”, police have disrupted nearly 40 “terrorist plots”.

“And we are doing that month-in, month-out, with real efficiency and effectiveness.”

Source Agencies