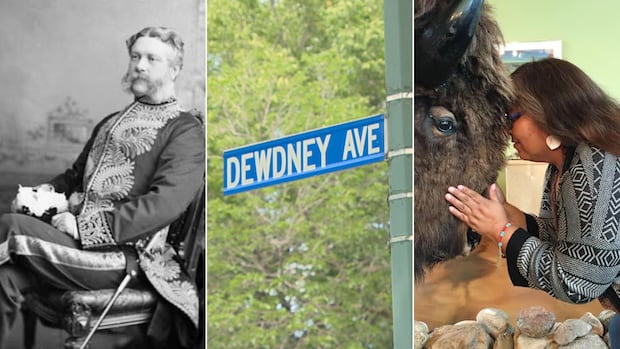

An internet search for Edgar Dewdney’s name will turn up many accounts of his contributions to Saskatchewan and to Canadian history, including his role in helping establish Regina as Saskatchewan’s capital city.

But there’s a dark truth behind that history — Dewdney also played a major part in early policy around the reserve system in Canada, and used starvation tactics against First Nations and Métis people in Saskatchewan in the 19th century.

Despite that, Dewdney is still honoured with a major avenue stretching across Regina named after him.

Two city councillors, Andrew Stevens (Ward 3) and Dan LeBlanc (Ward 6) brought a motion calling for a renaming of Dewdney Avenue to Regina city council.

But on Wednesday, council rejected the proposal in a 7-3 vote.

One councillor said the potential costs to businesses gave him pause. Mayor Sandra Masters has previously noted Dewdney Avenue is one of the city’s longest roads, and home to 2,500 businesses and residents.

But one woman who has been pushing for the name change for years says she’s disappointed by the result.

“I thought this was a great opportunity for them to resolve some conflict and to agree that this was a good thing in terms of reconciliation for the Indigenous community, “said Joely BigEagle-Kequahtooway, an Indigenous advocate who lives in Regina’s North Central neighbourhood.

Eight years ago, the city came to her to help work on changes related to truth and reconciliation.

The Dewdney Avenue name was one of them.

After she helped organize and submit a petition requesting that the city strip the Dewdney name from its assets, including a park, pool and the avenue, the pool and park were renamed Buffalo Meadows in 2021.

But this week’s vote is a slap in the face to her and the many organizations that supported changing the street name, she said, and sends the message that “they really don’t care about Indigenous people, and if it comes to money, then they care,”

She also said it raises questions about whether Regina is a safe place for Indigenous youth.

“Is it still holding on to those legacies of racism? Is Regina a racist city? Some people would argue yes,” said BigEagle-Kequahtooway.

She thinks the decision shows a lack of education about history and the realities Indigenous people in Canada have faced.

“This isn’t over, so I think this is just another opportunity for learning on how to navigate this colonial system to make our voices heard,” BigEagle-Kequahtooway said. “For me, that’s resilience. That’s how we’ve survived all these years.”

She said history shows that governments wanted Indigenous people to die off so they could take the land.

“To me, that’s what Edgar Dewdney wanted, and too bad for him, I’m not dead. There’s many Indigenous people within this community.”

Decision sends wrong message: prof

Rob Innes, an associate professor and the chair in Indigenous studies department at McMaster University in Hamilton, has written about Dewdney, in part because of “how very little is really known” about his role in a starvation policy intended to quell dissent and force Indigenous people out of the Cypress Hills area of southwest Saskatchewan.

“Dewdney had a huge impact in terms of his decisions costing hundreds, if not thousands, of First Nation and Métis people’s lives,” Innes said in an interview with CBC.

Dewdney, who was the commissioner of Indian affairs and lieutenant governor of what was then the North-West Territories, promised Indigenous people that food would be distributed at Fort Walsh, the North-West Mounted Police fort in the Cypress Hills in present-day southwestern Saskatchewan.

But in 1881, he introduced a policy under which the promised rations would only be provided to those who had accepted a treaty, Innes wrote in a 2021 article for CBC.

He later decided to close Fort Walsh, essentially using starvation to force First Nations and Métis people out of the area, wrote Innes.

“The ‘starvation policy’ becomes a euphemism for genocide … and this clearly was a genocide,” said Innes.

He said he isn’t surprised by the decision on renaming Dewdney Avenue, but it’s “still shocking that the city council still, in this day and age, would prefer to uphold the legacy of genocide rather than embrace reconciliation.”

WATCH | Activist disappointed by council’s decision:

Indigenous activist Joely BigEagle-Kequahtooway says she’s disappointed after Regina city council decided not to rename Dewdney Avenue, a street named after a man who helped institute Canada’s reserve system and establish residential schools.

He said he knows cities like Winnipeg, Toronto and Saskatoon have changed names connected with historical figures with problematic pasts.

Innes acknowledges the argument that there could be costs to renaming for the many businesses on Dewdney Avenue, which might not have been the case in renaming efforts in other cities.

But “this is the era of truth and reconciliation,” and the avenue runs “right smack in the middle” of the city, including through areas largely populated by Indigenous people, he said.

“It sends a message that … we don’t care about your history, we don’t care what happened to you. But you have to walk on the street, you have to go on the street every day.”

The message is that “we have to commemorate Dewdney because without him there is no Regina,” but “what they’re missing is that this is how … Regina has benefited from the deaths of Indigenous people,” he said.

Researcher saddened city ‘still honouring this man’

Matthew Spencer, a historical researcher from the Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation, has been looking into the history of his community.

Dewdney was appointed Indian commissioner in the late 1870s by then prime minister John A. Macdonald, who at the time was pushing for the construction of a cross-country railway.

“That railway was going to run north of the Cypress Hills, and that’s when began kind of the starvation of the First Nation bands out of the Cypress Hills.… That’s kind of how Carry the Kettle is tied directly to Edgar E. Dewdney,” said Spencer.

“He was the guy who helped create their reserves in the Cypress Hills, and he was also the guy who helped remove them and kind of starve them to their new location just south of Indian Head, Sask.”

Starving people displaced from the Cypress Hills area were denied rations guaranteed under treaty or given rancid food, Spencer said.

When Carry the Kettle’s chief at the time, Long Lodge, asked Dewdney for rations guaranteed through treaty provisions, he was told by Dewdney his people could “eat this salt pork or die,” said Spencer.

Knowing that history, Spencer said he’s saddened by Regina city council’s decision against renaming Dewdney Avenue.

“Because every time I drive down the street or go anywhere near it, I’m like … they’re still honouring this man who I believe committed genocide on our people.”

Source Agencies