Shutterstock

ShutterstockClimbing into his backyard jacuzzi that overlooked the Santa Monica Mountains, Matthew Perry uttered the seven words that would ultimately lead to his death: “Shoot me up with a big one.”

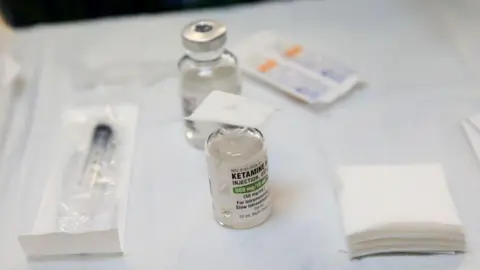

The big one, court documents would later reveal, was a dose of ketamine, a prescription anaesthetic and a hallucinogen that has become popular for its off-label uses to treat depression and anxiety. It was the actor’s third injection of the day.

Hours after that fatal dose, the “Friends” actor was found face down in the jacuzzi. Medics pronounced him dead at the scene with a coroner finding ketamine was his primary cause of death.

The details about Perry’s last day alive on 28 October 2023 were revealed in court documents following a police probe that ultimately led to five people being charged in relation to his death.

The documents offer an in-depth look by the law enforcement agencies into his drug addiction, which he struggled with for decades, and a glimpse into Hollywood’s ketamine drug network. Doctors and experts told the BBC the growth in ketamine’s popularity in recent years has caused the market to explode, with the expansion of ketamine clinics and online services offering easy prescription access to the drug, as well as a burgeoning illicit drug market.

“It’s super easy [to get], – be it underground or prescription,” Dr David Mahjoubi, who serves as president of the American Board of Ketamine Physicians, told the BBC. “I have celebrities that are getting a prescription from me. It’s super easy, not hard at all.”

An underground network

Federal authorities said their investigation into Perry’s death uncovered a “broad underground criminal network” of drug suppliers who distributed large quantities of ketamine across Los Angeles.

Federal court documents detail Perry’s last months alive and the transition from his treatments at a ketamine clinic for depression and anxiety, where a physician administered the drug and monitored for side effects, to an addiction that led him to “unscrupulous doctors” and a network of street dealers.

Perry had been open about his addiction problems, which stem back decades – even to his time playing Chandler Bing on “Friends”. If a drug entered his life, he seemed to become addicted.

But in his memoir Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, he said he’d finally gotten sober, and one woman told investigators at the coroner’s office that she believed he’d been sober for 19 months.

Somewhere in that time, he started receiving ketamine infusion therapy. Experts say Perry’s history of addiction helped lead him to quickly become hooked on the drug.

The federal investigation found that over a nearly two-month span before his death, Perry purchased dozens of vials of ketamine for thousands of dollars.

Over the three days before his death, his assistant injected him at least six times a day with ketamine shots.

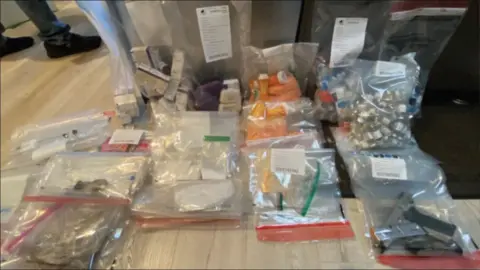

United States Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California

United States Attorney’s Office for the Central District of CaliforniaFive people were arrested in the probe – three of whom already pleaded guilty in the conspiracy. In total, the group faces 23 counts in Perry’s death.

- Kenneth Iwamasa: Perry’s live-in personal assistant pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to distribute ketamine causing death. He admitted to helping Perry find ketamine and repeatedly injecting him with the drug, including the dose that killed him.

- Dr Salvador Plasencia: A physician accused of supplying Perry with large quantities of ketamine, injecting him on multiple occasions – including in a public parking lot – and teaching his assistant how to inject him with doses. He has pleaded not guilty to all charges against him arising out of Perry’s death.

- Dr Mark Chavez: A physician who pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to distribute ketamine. He admitted to selling ketamine to Dr Plasencia, including drugs he had diverted from a ketamine clinic.

- Jasveen Sangha, described by law enforcement as the “The Ketamine Queen“: An alleged street dealer who court documents say was known to work with celebrities and high-end clients. She is accused of supplying the drugs that ultimately killed Perry. Authorities raided her home and discovered what they called a “drug-selling emporium” with dozens of ketamine vials and thousands of pills. She has pleaded not guilty to all charges against her, including conspiracy to distribute ketamine and distribution of ketamine resulting in death.

- Eric Fleming: A middleman who authorities say got drugs from Ms Sangha and distributed them to Perry and his assistant. He pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to distribute ketamine and one count of distribution of ketamine resulting in death.

Jasveen Sangha’s social media

Jasveen Sangha’s social media‘Yes men’

Numerous doctors and experts who spoke to the BBC for this story spoke about the toxic relationship between celebrity and medicine.

“The VIP treatment is usually not the best treatment,” Dr Gerard Sanacora, director of Yale University’s Depression Research Program, told the BBC.

“Doctors are humans, too, and despite taking the Hippocratic oath, not everyone abides by it,” he added, acknowledging doctors can “lose perspective when you have a VIP client” and there’s promises of invites to big parties or donations to research programs or charities.

Dr Mahjoubi, who operates two ketamine clinics in California – including one in Los Angeles – told the BBC that when celebrities are your patients, normal boundaries can be hard to maintain.

He said he was treating one unnamed celebrity who he offered his cell phone number to in case of emergencies.

The patient was “constantly trying to asking me favours – ‘hey, refill my prescription’- and it’s like Sunday evening.”

“I told him, ‘Look please email me anything medically related’ and blocked him,” Dr Mahjoubi said.

He also said he’s seen how ketamine has become a “go-to” party drug for celebrities, who think it is safer than something like cocaine, which can be laced with deadly drugs like fentanyl.

Another Los Angeles area doctor, who operates several pain management centres – another condition ketamine is marketed to – called the spread of ketamine treatments the new “wild west”.

He spoke to the BBC on the condition of anonymity to candidly discuss ketamine’s popularity, detailing the nuanced relationships he’s witnessed between doctors and some celebrities.

Everyone wants to be a “doctor to the stars here”, the doctor explained. Some will go so far as offering free treatments or closing down their clinic or office for private access, all with the hope the celebrity patient will post about their treatment on social media.

“There are celebrities who are passed around from doctor-to-doctor and they are fought over,” the doctor added, calling it both “a weird relationship” and troubling business model.

A lot of these stars are “used to being told ‘yes’,” he said.

“If you don’t, they’ll just go to someone else who will give them what they want.”

Being surrounded by “yes men” can have life-changing ramifications, said Garrett Braukman, the executive director of the Alta Centers, a rehabilitation and detox treatment centre in Hollywood. About 20 to 30% of patients work in the film industry.

He said he’s seen an uptick in ketamine addiction, but its not outpacing commonly abused substances like alcohol, cocaine and opioids.

“People often get into the arts because of things they’ve experienced – a lot of time that’s trauma,” Mr Braukman said. When you add in Los Angeles’ fairly “normalized” drug culture and celebrity access, “it’s the perfect recipe for addiction,” he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe start of a new prescription epidemic?

A simple Google search for “ketamine prescription” reveals a handful of advertisements for online companies touting the benefits of “psychedelic therapy” to treat illnesses from depression and anxiety to Lyme disease and chronic pain, some offering a subscription for just $100 a month to get the drug.

One problem: The drug isn’t approved to treat those conditions.

The US Food and Drug Administration – the regulatory agency responsible for approving drugs and ensuring they’re safe, work and labelled properly – has only approved ketamine for general anaesthesia used under the care of a physician.

In 2019, the FDA approved a nasal-spray drug that is made from ketamine and okayed its use to treat depression, so long as the drug is coupled with additional therapy and administered under the direct supervision of a doctor. The doctor must also monitor the patient for two hours after the dose has been taken for potential side effects, which include hallucination, feeling disconnected from reality and increased blood pressure.

But these online clinics have exploited a grey area in the regulations to market off-label ketamine prescriptions directly to consumers, experts say.

While FDA advertising regulations restrict pharmaceutical companies that “manufacture, distribute, or pack”, they do not restrict new start-ups, like online “wellness” clinics.

“It’s a very tricky thing – it’s a loophole almost,” Dr Sanacora told the BBC.

Two weeks before Perry’s death, the FDA warned consumers about ketamine’s off-label use, noting “the lack of monitoring for adverse events, such as sedation and dissociation, by an onsite health care provider may put patients at risk”.

Doctors and experts say the market seemed to boom during the pandemic, when online telehealth services, clinics and at-home care proliferated.

The pain management doctor, who had spoken to the BBC on condition of anonymity, said some of these companies are structured in ways that “don’t want people to get better” but rather, to keep them on prescription subscriptions that keep money pouring in.

“It’s gotten out of hand,” he said.

Dr Sanacora, who has studied and researched how ketamine can be used to treat depression, said there is a lot of evidence of the drug’s efficacy. Drug trials are currently underway testing the merits of ketamine treatment for treatment-resistant depression.

But much is still not known about why it works, and it does come with risks, such as seizures and death.

Dr Sanacora said it’s unclear whether overdoses have increased, because the federal government does not track ketamine-related deaths, which it does for cocaine, heroin and opioid overdoes. Sometimes the drug is not even tested for during autopsies.

“There’s a lot we really don’t know,” he said.

The DEA’s chief Anne Milgram said the agency is targeting doctors who are over prescribing these drugs or prescribing it when it is not necessary.

Speaking with CBS News, the BBC’s US news partner, she compared ketamine and its use in the Perry case with the start of the opioid epidemic in the US.

“This, unfortunately, is a tragic arc that we have seen thinking back to the beginning of the opioid epidemic, where many Americans became addicted to controlled substances in doctors’ offices and through medical practitioners that then turned into street addiction as well.”

Source Agencies