By this time next year, the childhood home of Baltimore philanthropist and university namesake Johns Hopkins is likely to be history, said its new owner, Sam Asgari.

The historic Gambrills house is headed toward either demolition or collapse if it doesn’t receive a major cash infusion soon, said Asgari, who recently purchased actor Kevin Spacey’s Baltimore condo for $3.24 million.

When the Potomac-based real estate investor purchased the 13-acre Hopkins property in January for $915,000, Asgari said he planned to turn it into a museum and inn or wedding hall.

Then he toured it.

Broken windows line the 18th-century home’s front exterior, staircases sag, and chandeliers are shattered. The flooring is stained and warped, and drywall is crumbling from the ceiling exposing the underlying foundation of the floor above.

“We knew we were getting something that’s complicated, but not this complicated,” Asgari said.

It appeared, to Asgari, that the property hadn’t been maintained in several years, despite a nonprofit, Johns Hopkins House Inc., spending six years fundraising for its restoration.

Hopkins was born in 1795 to Quaker parents, and raised on the property and former tobacco plantation also known as Whites Hall, according to the Johns Hopkins University. Quaker edict dictated followers liberate the people they enslaved decades before emancipation. Evidence suggests Hopkins’ family followed that directive and freed or created terms to free the people they enslaved there before 1800. Emancipation wouldn’t become law in Maryland until 1864.

Johns Hopkins left home at 17 and moved to Baltimore to work for his uncle in the wholesale grocery business.

The philanthropist is best known for the work he did after leaving Gambrills. According to the school, that included financing America’s first research university; a hospital designed to treat people of all races, ages, and genders; and an orphanage serving Black children in Baltimore.

Last fall, the state shut down the nonprofit fundraising for the home for allegedly misleading donors. A few months later the parcel was sold to Asgari at a foreclosure auction.

Upon assessing the house at the start of the year, Asgari started to lose hope in his ability to restore it and protect its history. Not only were the aesthetics of the home in dire need of triage, but the very structural integrity of the building was at stake, he learned.

The roughly 24-inch foundation was cracking and the building’s middle support beams were “sinking drastically,” said Gustavo Martinez, Asgari’s general supervisor for the property, adding it was also missing its copper piping, leaving the building without running water.

Improvements would likely total around $1 million, Martinez said. Asgari wasn’t eager to spend more money fixing the house than he bought it for in the first place, he said.

He attempted to acquire financial assistance from Anne Arundel County and from contacts of his at the university. Neither could or was willing to provide help.

The local government doesn’t typically allocate funds to private property owners, wrote C. Jane Cox with the county’s historic preservation program. Meanwhile, the university isn’t interested in maintaining another historic parcel, said university spokesperson J.B. Bird.

Asgari conceded and listed the home for sale, gradually lowering the price from about $1.9 million to around $1.5 million.

“Everyone who looks at it is like: ‘No, it’s in really bad shape,’” he said.

If the home is not purchased or he doesn’t somehow receive substantial financial assistance, he said, he’ll have to tear down the structure. However, the house’s fate may not be up to him.

“Without help, that house is going to come down by itself,” Asgari said. “In less than a year.”

Losing the Hopkins house could curtail further research into the lives of Hopkins and his family members, Quaker history and the complexities of how slavery functioned and concluded in the 18th and 19th centuries, according to historians, professors and archivists knowledgeable about Hopkins’ life.

Questions about Hopkins and the values with which he led his life still swirl today among historians and professors. Whether he enslaved people, despite being known as a staunch abolitionist, has been debated since the university announced in 2020 the finding of documents indicating enslaved people may have lived in his home.

Hopkins did, however, draft a very consequential will, making contributions that led to the Johns Hopkins University and hospital. That’s something he may not have done without having the upbringing he did in that home, said Sydney Van Morgan, a senior lecturer at the university who is teaching a class about Hopkins in the fall and writing a biography on his life.

“It was those Quaker principles and the discipline that led him to have the life that he did — not a perfect life, and certainly not looking back from the viewpoint of the 20th century — but he did a lot of good with what he had,” she said.

Show Caption1 of 14

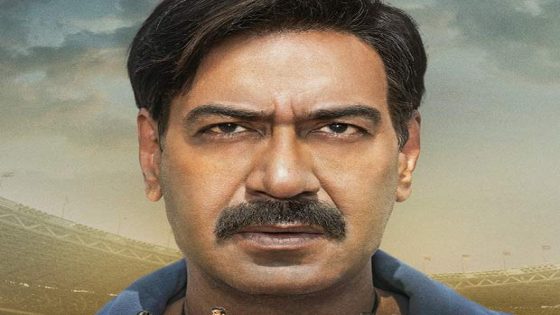

Aug. 20, 2024: The Johns Hopkins House: Built in circa 1780, Whites Hall, also referred to as Whiteshall or Whites Hall Farm, is the birthplace and boyhood home of famous Maryland native Johns Hopkins., who went on to found the world-renowned university and hospital that bear his name. (Jeffrey F. Bill/Staff photo)

Source Agencies