Getty Images

Getty Images“Think of it as cricket cake, like fish cake,” the chef said as he urged the man in the buffet line to try the steaming, spicy laksa – a coconut noodle broth – full of “textured cricket protein”.

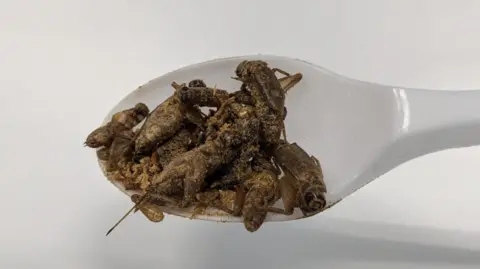

Next to it was a plate of chilli crickets, the bug version of a beloved Singaporean dish – stir-fried mud crabs doused in a rich, sweet chilli sauce.

It looked like any other buffet, except for the main ingredient in every dish: crickets.

The line included a woman who gingerly scooped stir-fried Korean glass noodles topped with minced crickets onto her plate, and a man who wouldn’t stop grilling the young chef.

You would have expected the diners to snap up the feast. After all, they were among more than 600 scientists, entrepreneurs and environmentalists from around the world who had descended on Singapore as part of a mission to make insects delicious. The name of the conference said it all – Insects to Feed the World.

And yet more of them were drawn to the buffet next to the insect-laden spread. It was the usual fare, some would have argued: wild-caught barramundi infused with lemongrass and lime, grilled sirloin steak with onion marmalade, a coconut vegetable curry.

Some two billion people, about a quarter of the world’s population, already eat insects as part of their everyday diet, according to the United Nations.

More people should join them, according to a growing tribe of bug advocates who champion insects as a healthy and green choice. But is the prospect of saving the planet enough to get people to sample their top creepy crawlies?

à la insects

“We have to focus on making them delicious,” said New York-based chef Joseph Yoon, who designed the cricket-laced menu for the conference, along with Singaporean chef Nicholas Low. The event had permission to use only crickets.

“The idea that insects are sustainable, dense with nutrients, can address food security, and so on,” is not enough to make them palatable, let alone appetising, he added.

Studies have found that just six crickets met a person’s daily protein needs. And rearing them required less amount of water and land, compared with livestock.

Some countries have given insect diets a nudge, if not a push. Singapore recently approved 16 types of bugs, including crickets, silkworms, grasshoppers and honey bees, as food.

It is among a handful of countries, inlcuding the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and Thailand, that are regulating what is still an incipient edible insects industry. Estimates vary from $400m to $1.4bn (£303m to £1.06bn).

Insects to Feed the World

Insects to Feed the WorldEnter chefs like Nicholas Low who have had to find ways to “break down” insects to cook with them because people are not always up for trying them “in their original form”.

For the conference, Mr Low reinvented the popular laksa when he replaced the usual fishcake with patties made of minced cricket.

He said it also took some work to mask the earthy smell of the insects. Dishes with “strong flavours”, like laksa, were ideal because the delights of the original recipe distracted people from the crushed bugs.

Mr Low said crickets left little room for him to experiment. Usually deep-fried for a satisfying crunch, or ground to a fine powder, they were unlike meats, which made for versatile cooking, from braises to barbecue.

He could not imagine cooking with crickets every day: “I’m more likely to cook it as a special dish that is part of a larger menu.”

Since Singapore approved cooking with bugs, some restaurants have been trying their hand at it. A seafood spot has taken to sprinkling crickets on their satays and squid ink pastas, or serving them on the side of a fish head curry.

Of course there are others who have been more committed to the challenge. Tokyo-based Takeo Cafe has been serving customers insects for the past 10 years.

The menu includes a salad with twin Madagascar hissing cockroaches nestling on a bed of leaves and cherry tomatoes, a generous scoop of ice cream with three tiny grasshoppers perched on it and even a cocktail with spirits made from silkworm poo.

BBC/Kelly Ng

BBC/Kelly Ng“What’s most important is [the customer’s] curiosity,” said Saeki Shinjiro, Takeo’s chief sustainability officer.

What about the environment? “Customers are not concerned so much,” he said.

Just to be on the safe side, Takeo also has a bug-free menu. “When designing the menu, we keep in mind not to discriminate against people who do not eat insects… Some customers are merely here to accompany their friends,” Mr Shinjiro said.

“We do not want such people to feel uncomfortable. There is no need to eat insects forcibly.”

Our food and us

It hasn’t always been this way, though. For centuries, insects have been a valued food source in different parts of the world.

In Japan grasshoppers, silkworms, and wasps were traditionally eaten in land-locked areas where meat and fish were scarce. The practice resurfaced during food shortages in World War Two, Takeo’s manager Michiko Miura said.

Today, crickets and silkworms are commonly sold as snacks at night markets in Thailand, while diners in Mexico City pay hundreds of dollars for ant larvae, a dish once considered a delicacy by the Aztecs, who ruled the region in the 15th and 16th Centuries.

But bug experts worry that these culinary traditions have been unravelling with globalisation, as people who eat insects now associate the diet with poverty.

There is a “growing sense of shame” in places with a long history of insect consumption, like Asia, Africa and South America, said Joseph Yoon, the New York-based chef.

“They now get glimpses of foreign cultures over the internet and they are embarrassed about eating insects because that is not the practice elsewhere.”

Insects to Feed the World

Insects to Feed the WorldIn her book Edible Insects and Human Evolution, anthropologist Julie Lesnik argued that colonialism deepened the stigma of eating insects. She wrote that Christopher Columbus and members of his expedition described the native Americans’ consumption of insects as “bestiality… greater than that of any beast upon the face of the earth”.

Of course, people’s attitudes could change. After all, gourmet treats such as sushi and lobster were once an alien concept to most people.

Sushi started out as a working-class dish found in street stalls. And lobsters, known as the “poor man’s chicken”, were once fed to prisoners and slaves in north-eastern America because of their abundance, said food researcher Keri Matiwck from Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

But as transport networks made travel easier and food storage improved, more and more people were introduced to the crustacean. As demand increased, so did its price and status.

Foods once seen as “exotic”, or not even regarded as food, can gradually become mainstream, Dr Matwick said. “[But] cultural beliefs take time to change. It will take a while to change the perceptions of insects as disgusting and dirty.”

Some experts encourage people to raise their children to be more tolerant of unusual food, including insects, because future generations will face the full consequences of the climate crisis.

Insects may well become the “superfoods” of the future, as coveted as quinoa and berries. They may be grudginly eaten, rather than sought out for the joy that a buttery steak or a hearty bowl of ramen brings.

For now, Singapore chef Nicholas Low believes there is nothing pushing people to change their diets, especially in wealthy places where almost anything you want is a few clicks away.

Younger consumers may be willing to taste them out of curiosity, but the novelty will wear off, he said.

“We are spoilt for choice. We like our meat as meat, and our fish as fish.”

Source Agencies