Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Engineers at NASA have successfully fired up a set of thrusters Voyager 1 hasn’t used in decades to solve an issue that could keep the 47-year-old spacecraft from communicating with Earth from billions of miles away.

When Voyager 1 lifted off to space on September 5, 1977, no one expected that the probe would still be operating today.

As a result of its exceptionally long-lived mission, Voyager 1 experiences issues as its parts age in the frigid outer reaches beyond our solar system. When an issue crops up, engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, have to get creative while still being careful of how the spacecraft will react to any changes.

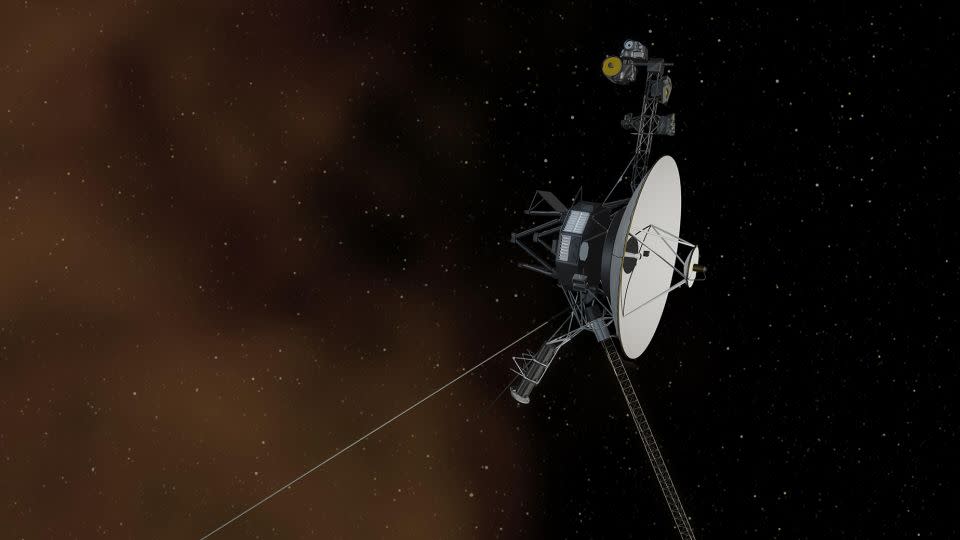

Currently the farthest spacecraft from Earth, Voyager 1 is about 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away. The probe operates beyond the heliosphere — the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond Pluto’s orbit — where its instruments directly sample interstellar space.

Earlier this year, engineers spotted an issue when the fuel tube inside one of Voyager’s thrusters became clogged. If the thrusters are clogged, they can’t generate as much force to keep the spacecraft steady. Voyager’s thrusters keep the spacecraft oriented in a way that it can communicate with Earth.

If Voyager 1 isn’t positioned in such a way so that its antenna is pointed at Earth, the spacecraft can’t “hear” commands from mission control or send back data, according to Calla Cofield, media relations specialist at JPL.

“If the thrusters that keep the antenna pointed at Earth get clogged, that would be end of mission,” she said.

The team realized it would have to send commands to the spacecraft to switch to another set of thrusters, but the fix wouldn’t be a simple one.

A recurring problem

It’s not the first time Voyager 1 has needed to switch over to another set of thrusters in recent decades. Fortunately, the spacecraft has three sets of thrusters: two sets of attitude propulsion thrusters and one set devoted to trajectory correction maneuvers.

Voyager 1 used the thrusters for a variety of purposes as it flew by planets such as Jupiter and Saturn in 1979 and 1980, respectively.

Now, the spacecraft is traveling on an unchanging path away from our solar system, so it just requires one set of thrusters to help keep its antenna pointed at Earth. To fuel the thrusters, liquid hydrazine is converted into gas and released in about 40 short puffs per day to keep Voyager 1 oriented correctly.

Over time, engineers discovered that a fuel tube inside the thrusters can become clogged with silicon dioxide, a byproduct of the fuel tank’s rubber diaphragm aging. As the thrusters become clogged, they generate less force.

In 2002, the team commanded Voyager 1 to switch to its second set of attitude propulsion thrusters when the first set showed signs of clogging. Engineers switched again to the trajectory correction thruster set in 2018 when the second set also appeared clogged.

But when the team recently checked on the status of Voyager’s trajectory correction thrusters, they were even more clogged than the previous two sets of thrusters.

When the team initially switched Voyager over to the trajectory correction thrusters six years ago, the tube opening was 0.01 inches (0.25 millimeters) across. But now, clogging has reduced it to 0.0015 inches (0.035 millimeters) — half the width of a human hair, according to NASA.

It was time to rotate back to another set of attitude propulsion thrusters.

Making a challenging swap

As Voyager 1 and its twin probe, Voyager 2, have aged, the mission team has slowly turned off nonessential systems on both spacecraft to conserve power, including heaters. As a result, components on Voyager 1 are colder now, and the team knew it couldn’t just send a command to Voyager 1 to switch immediately to one of the attitude propulsion thrusters without doing something to warm them up.

But Voyager 1 doesn’t have enough power to switch any heaters back on without turning something else off, and its scientific instruments are too valuable to shut off in case they don’t come back on, the team said.

After going back to the drawing board, the team realized it could shut off one of the spacecraft’s main heaters for about an hour, which would enable engineers to turn on the thruster heaters and safely make the switch.

This plan worked, and by August 27, Voyager 1 was back to relying on one of its original thruster sets to stay in touch with Earth.

The team has taken steps to use the thrusters less, and it is expecting to get another two to three years out of the original set, said Todd Barber, Voyager propulsion engineer.

Once the spacecraft has exhausted this thruster set, Voyager 1’s remaining option is the other already clogged set of attitude propulsion thrusters.

“All the decisions we will have to make going forward are going to require a lot more analysis and caution than they once did,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager, in a statement.

Voyager 2 has also gone through thruster swaps in 1999 and 2019, and “the situation there is less dire,” Barber said. Voyager 2 has traveled more than 12 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) from Earth.

The information collected by these long-lived probes is helping scientists learn about the cometlike shape of the heliosphere and how it protects Earth from energized particles and radiation in interstellar space.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Source Agencies