I’ve seen documentaries reveal fascinating dimensions of John Lennon — films like “The U.S. vs. John Lennon” (2006), which chronicled his political activism and the Nixon administration’s attempts to deport him, or “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” (2022), a portrait of Lennon’s relationship with May Pang. But “One to One: John & Yoko,” despite its rather nondescript title, may be the most accomplished and arresting of these tightly angled Lennon profiles. “The Lost Weekend” showed us a side of Lennon that had been somewhat under the radar (including his propensity for violence, which has never been widely talked about outside of Albert Goldman’s scandalous deep-dive biography “The Lives of John Lennon”). “One to One” deals with the period just before the Lost Weekend, starting in August 1971, when John and Yoko moved from their country estate outside London to New York City, where they spent 18 months living in a small apartment in the West Village. (It was after that that they moved into the Dakota.)

Lennon was out and about, digging the city, appearing on American talk shows like “Mike Douglas,” grooving on the relative non-chaos of his life after the Beatles. And much of this has a familiar aura. But “One to One” was made by the accomplished and at times audacious Scottish director Kevin Macdonald, whose films range from “Touching the Void” to “The Last King of Scotland” to “Whitney,” and he lures us into John Lennon’s life, and the entire period, in an uncanny way.

The film takes off from something that Lennon spoke of openly, but for many of us it went in one ear and out the other — namely, that after he’d moved to New York and embraced America, he became a TV addict. I always thought this was rather funny, since Lennon, in the early ’70s, still had his counterculture bona fides and was at the vanguard of a number of protest movements. Yet his acknowledgment that just about his favorite activity was zoning out in front of the television sort of presaged — beyond his more famous endeavors — where the entire culture was heading.

Lennon could be an idealist about politics (“Nothing to kill or die for, and no religion too…”), but in more ways than not he was a royal cynic, steeped in the anti-romanticism of his acidic take on reality. (Just listen to the lyrics of “Revolution.”) And that’s what a certain kind of smart person’s TV addiction is about, and certainly was back then: surfing through everything — the commercials, the shows that are mostly junk, the news that’s packaged, in many ways, just like a commercial — so that you’d soak it up like a sponge and, at the same time, go off on it, be subtly superior to it, collude in the decadent Western couch-potato act of experiencing everything under the sun as a show.

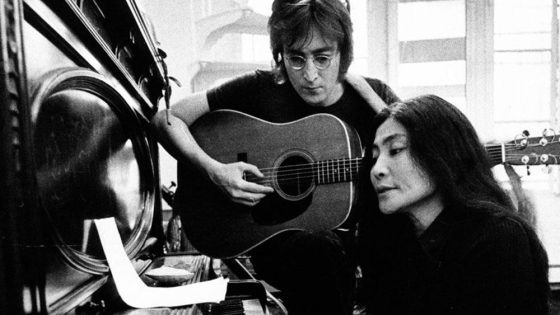

John and Yoko weren’t couch potatoes — they were bed potatoes. Macdonald and his team have erected an unnervingly accurate reconstruction of the couple’s white-walled duplex apartment at 105 Bank St. We never see the apartment occupied by people, but as the camera glides around we notice where every last thing is — the bed, the TV sitting at the foot of it, the strewn-about detritus of John and Yoko’s lives (guitars, clothes, an amplifier, a typewriter, newspapers and magazines, a Snoopy pillowcase). “One on One” is full of home movies and candid photographs, and with that mock-up of an apartment right in front of us, we can just about place the John and Yoko we’re seeing inside it.

Macdonald frames the period in other key ways. “One to One” takes its title from a pair of benefit concerts that Lennon gave at Madison Square Garden with the Plastic Ono Elephant’s Memory Band on August 30, 1972. It would be his last full-length concert performance, and what’s staggering, seeing it now, is what a powerful kick the music delivers. The band sounded extraordinary — so sharp and alive, as Lennon leads them through songs from the resounding opening number, “New York City,” to “Instant Karma” to “Come Together” to the stripped-down epiphany of Lennon’s raw-throated performance of “Mother.”

The music gives the film shape and propulsion. But so does the way that Macdonald, keying off Lennon’s TV habit, presents images of the period as an ongoing channel-surfing montage. We see Nixon, “The Waltons,” the Attica State uprising, Jerry Rubin on “Phil Donahue,” a Ragu commercial, the shooting of George Wallace, the return from exile of Charlie Chaplin, and other events and media tidbits that tweak you with their hanging-in-the-air early-’70s quality. The thing about 1971 and 1972 is that the new right was starting to rise, but no one knew it yet, and the messianic underpinnings of the counterculture (“We’re changing the world, man!”) were starting to run on empty, but no one knew that yet either. It was a great big moralistic hangover.

You really feel that as the film documents John and Yoko’s relationship with Jerry Rubin, who’d become a celebrity during the Chicago 7 trial, and who liked his fame a little too much. If Abbie Hoffman was the yippie as ebullient prankster, Rubin was the yippie as huckster — a salesman of revolution who never met an audience he couldn’t feel superior to. Yet he seduced Lennon into teaming up with him, an association that began when Lennon performed at the Free John Sinclair rally in Ann Arbor, Mich. We see rare footage of that fabled concert, and I don’t think Lennon, singing “John Sinclair” (“It ain’t fair, John Sinclair,/In the stir for breathin’ air”), comes off very well in it. But the event succeeded in springing the White Panther Party founder from his 10-year prison sentence for marijuana, and Rubin, who’d become close to Lennon, got him to agree to collaborate on the Free the People tour, which would be a traveling rock ‘n’ roll circus of protest politics. But the whole thing wound up falling apart.

We can hear why as we listen in, startled, on John and Yoko’s phone calls, a number of which are presented, with transcripts against a black background, in “One to One.” Lennon’s phone was, by this point, already being tapped by the FBI, and we can presume that these tapes (the filmmakers, for the record, are not saying this) are from that trove of surreptitiously recorded documents. But there’s nothing scandalous going on. We hear the comedy of Yoko’s associate attempting to wrangle a trove of insects for one of her art installations. We hear Lennon preaching purist politics to Allen Klein, the manager who played a part in breaking up the Beatles, and Klein is too worldly to be drawn into Lennon’s radical dreams — but too smart not to turn on a dime and suddenly pretend that yes, he can feel the spirit too. (This is the dark heart of what managing is.) We hear Jerry Rubin’s performative left-wing guilt-tripping. Mostly, we hear what a jovial and open chap Lennon, even with his bullshit detector, really was.

We can also hear what a keen observer Yoko was, and how she felt shut out by the Beatles (“They ignored me”). Part of the film’s emotional backdrop is how ahead of his time John was in placing Yoko’s wishes before his. The reason they came to New York in the first place was to search for Kyoko, Yoko’s estranged daughter from her second marriage, who they never did find (she was being raised, under a different identity, in a Christian cult). They moved into a modest bohemian flat because that was Yoko’s wish. (She was from a monied background and didn’t find their country mansion as novel as the working-class John did.)

“One to One” charts Lennon’s close friendship with Elton John, though at this point the film is cheating a bit, since that all happened later — in 1973 and 1974, which is when their exhilarating hit-single duet, Lennon’s “Whatever Gets You Through the Night,” was released. But this is no big deal, since very little about John Lennon was simple or consistent. In the early ’70s, he truly was a walking contradiction: a radical who sat around watching television; a powerful rock star who devoted himself to pleasing and honoring his avant-garde wife, even as he held onto his prickly libertine edge; a dyed-in-the-wool Brit who became the ultimate New Yorker. All of that ripples through “One to One,” making it the rare rock doc that’s a must-see.

Source Agencies