As AI deepfakes cause havoc during other elections, experts warn the UK’s politicians should be prepared.

“Just tell me what you had for breakfast”, says Mike Narouei, of ControlAI, recording on his laptop. I speak for around 15 seconds, about my toast, coffee and journey to their offices.

Within seconds, I hear my own voice, saying something entirely different.

Follow the latest updates on the election

In this case, words I have written: “Deepfakes can be extremely realistic and have the ability to disrupt our politics and damage our trust in the democratic process.”

We have used free software, it hasn’t taken any advanced technical skills, and the whole thing has taken next to no time at all.

This is an audio deepfake – video ones take more effort to produce – and as well as being deployed by scammers of all kinds, there is deep concern, in a year with some two billion people going to the polls, in the US, India and dozens of other countries including the UK, about their impact on elections.

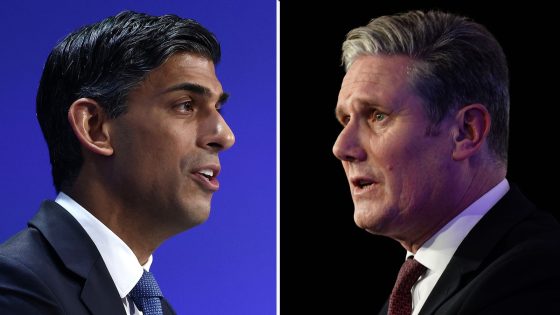

Sir Keir Starmer fell victim to one at last year’s Labour Party conference, purportedly of him swearing at staff. It was quickly outed as a fake. The identity of who made it has never been uncovered.

London mayor Sadiq Khan was also targeted this year, with fake audio of him making inflammatory remarks about Remembrance weekend and calling for pro-Palestine marches going viral at a tense time for communities. He claimed new laws were needed to stop them.

Ciaran Martin, the former director of the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre, told Sky News that expensively made video fakes can be less effective and easier to debunk than audio.

“I’m particularly worried right now about audio, because audio deepfakes are spectacularly easy to make, disturbingly easy”, he said. “And if they’re cleverly deployed, they can have an impact.”

Those which have been most damaging, in his view, are an audio deepfake of President Biden, sent to voters during the New Hampshire primaries in January this year.

A “robocall” with the president’s voice told voters to stay at home and “save” their votes for the presidential election in November. A political consultant later claimed responsibility and has been indicted and fined $6m (£4.7m).

Read more:

The digital election in India

Time running out for regulators to tackle AI threat

Biden to unveil sweeping AI regulations

Mr Martin, now a professor at the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University, said: “It was a very credible imitation of his voice and anecdotal evidence suggests some people were tricked by that.

“Not least because it wasn’t an email they could forward to someone else to have a look at, or on TV where lots of people were watching. It was a call to their home which they more or less had to judge alone.

“Targeted audio, in particular, is probably the biggest threat right now, and there’s no blanket solution, there’s no button there that you can just press and make this problem go away if you are prepared to pay for it or pass the right laws.

“What you need, and the US did this very well in 2020, is a series of responsible and well-informed eyes and ears throughout different parts of the electoral system to limit and mitigate the damage.”

He says there is a risk to hyping up the threat of deepfakes, when they have not yet caused mass electoral damage.

A Russian-made fake broadcast of Ukrainian TV, he said, featuring a Ukrainian official taking responsibility for a terrorist attack in Moscow, was simply “not believed”, despite being expensively produced.

The UK government has passed a National Security Act with new offences of foreign interference in the country’s democratic processes.

The Online Safety Act requires tech companies to take such content down, and meetings are being regularly held with social media companies during the pre-election period.

Democracy campaigners are concerned that deepfakes could be used not just by hostile foreign actors, or lone individuals who want to disrupt the process – but political parties themselves.

Polly Curtis is chief executive of the thinktank Demos, which has called on the parties to agree to a set of guidelines for the use of AI.

She said: “The risk is that you’ll have foreign actors, you’ll have political parties, you’ll have ordinary people on the street creating content and just stirring the pot of what’s true and what’s not true.

“We want them to come together and agree together how they’re going to use these tools at the election. We want them to agree not to create generative AI or amplify it, and label it when it is used.

“This technology is so new, and there are so many elections going on, there could be a big misinformation event in an election campaign that starts to affect people’s trust in the information they’ve got.”

Deepfakes have already been targeted at major elections.

Last year, within hours before polls closed in the Slovakian presidential election, an audio fake of one of the candidates claiming to have rigged the election went viral. He was heavily defeated and his pro-Russian opponent won.

The UK government established a Joint Election Security Preparations Unit earlier this year – with Whitehall officials working with police and security agencies – to respond to threats as they emerge.

A UK government spokesperson said: “Security is paramount and we are well-prepared to ensure the integrity of the election with robust systems in place to protect against any potential interference.

“The National Security Act contains tools to tackle deepfake election threats and social media platforms should also proactively take action against state-sponsored content aimed at interfering with the election.”

A Labour spokesperson said: “Our democracy is strong, and we cannot and will not allow any attempts to undermine the integrity of our elections.

“However, the rapid pace of AI technology means that government must now always be one step ahead of malign actors intent on using deepfakes and disinformation to undermine trust in our democratic system.

“Labour will be relentless in countering these threats.”

Source Agencies