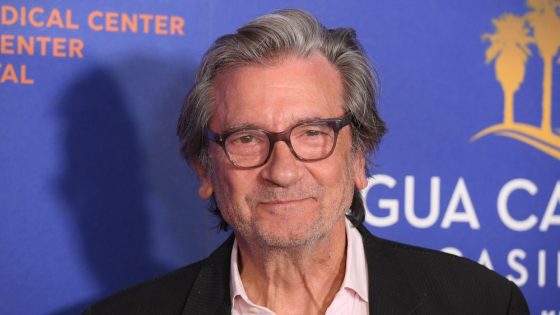

Griffin Dunne‘s family has done so many larger-than-life, unbelievable things that when the actor-director-producer started to write his memoir “The Friday Afternoon Club: A Memoir of Family,” he realized it wasn’t enough to start the story with his complex writer father Dominick Dunne.

In fact, it was impossible to understand the forces that shaped the Dunnes, including his uncle John Gregory Dunne and sister Dominique Dunne — without understanding his father’s abusive upbringing in an Irish Catholic family, his mother’s Mexican heritage and all great love stories, clandestine affairs, celebrity encounters and tragedies that seem to surround them, buffeted with lots of pitch-black mordant humor.

The heart of the new memoir is the 1982 murder of Griffin Dunne’s younger sister, “Poltergeist” star Dominique Dunne. It’s the first time he’s really grappled with telling the story of that pivotal event in his family’s history. The pain of her loss was intertwined with the rise of his father’s magazine writing career, after Dominick Dunne wrote about the trial for Vanity Fair.

Griffin Dunne, who recently played a character based on David Carr in Max’s “The Girls on the Bus,” displays his family’s gift for melding deft humor while recounting catastrophic events as he remembers the significant figures in his life including his best friend Carrie Fisher, his aunt Joan Didion and his brother Alex Dunne. Along the way Griffin Dunne drops revelations about his father’s hidden life, coming to terms with his own sexuality during a time when a party guest casually groping a teenager wasn’t discussed, not to mention his mother’s stillbirths and other traumatic moments.

Variety talked to Dunne about his family, career and growing up in Beverly Hills during the last gasps of old Hollywood.

Why was this the right time for a memoir?

Writing a book had been in the back of my mind on a very small bucket list: to write a book, learn Spanish and play the guitar. And I’ve only gotten as far as the book.

You started out with the idea of writing a series of anecdotes like David Sedaris does. What changed?

The whole book changed for me once I realized that to start at the beginning, I had to start with the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa driving my mother’s side of the family to the border town of Nogales, and my father’s side of the family that began with the Great Famine. Then as I wrote about my parents’ childhood and my mother’s only-child, lonely upbringing on a cattle ranch in Arizona and my father’s rather painful childhood, with abuse by his father, the book took on a form where I knew that I would be headed in the direction from the moment Dominique was born. Once I wrote that, I knew that I was going to be dealing with her murder and the trial that followed.

The story starts in media res, with the police coming to your mother’s house. Why did you want to go over her death when your father had already written about it?

I took the first moment of realization of the murder with a detective coming to my mother’s house, and I made that the prologue, and then I realized that Dominique was the pulse all the way through it. I wanted the reader to really get to know my family, because after all the things that they went through, how they emerged on the other side was incredibly moving to me. Part two was the demarcation and all of our lives were forever different. My father had written very beautifully about the trial in his very first published piece in Vanity Fair, called “Justice,” but that was from the point of view of a father. When you’re a sibling, it’s a very different experience.

At one point, you describe your childhood in Santa Monica and then Beverly Hills as “ridiculous.” Sean Connery saved you from drowning in a swimming pool, and Truman Capote was inspired by your parents’ fabulous Black and White Ball to throw his own iconic soirée. The “Friday Afternoon Club” refers to your mother’s weekly parties where young George Clooney would drop by. Why was it ridiculous?

Well, the night of the black and white ball, we were packed up in our PJs and matching bathrobes and nightgown and checked into a hotel. We had our homework with us. It was very strange. Beverly Hills is a place that, when I got older I was kind of embarrassed to say I was from. It just tagged me as a rich kid. Particularly when I moved to New York, that was not the narrative I wanted to present.

For a time, your father had some success as a producer, but he was always obsessed with famous people. What was that about?

At that time, he placed such tremendous importance on celebrity. He valued himself by the amount of famous people who came to his house. When I look back on it, it just sort of seemed sort of ridiculous how important these parties were. My father would would keep these huge leather-bound scrapbooks and iron the pictures of everyone who came over and the telegrams accepting invitations to his parties.

I hope you kept them!

They’re right here! (Dunne swivels the Zoom camera toward a table piled with 60-year-old scrapbooks.) I now regard them as priceless documents about a period in Hollywood, from 1960 to 1966, that is little-known. There weren’t the greatest movies being made at the time, and the studios had lost touch with who their audience would be. One of the guests at the Black and White Ball was Dennis Hopper, and in three or four years from that ball, he would be making “Easy Rider” and Hollywood would never be the same and the audiences would never be the same. And the people who ran studios would never be the same.

It was a cruel irony that writing about your sister’s murder enabled your father to find a new career after a difficult time in his life. How were you able to reconcile that?

Dad told me that he whispered into Dominique’s ear when she was on life support. He said, “I whispered in her ear, ‘give me your talent.’” I thought that was an incredibly beautiful and a tough and a terribly honest thing to say. He was by that time a recovered alcoholic, had lost everything, all of his money and sold all his possessions and had come back from living in a cabin by himself in Oregon, and he was a very different man than the man I grew up with.

When this article, “Justice,” came out in Vanity Fair, it felt terribly fresh. What we went through as a family unit — we were so close and it was so intimate. It felt like an invasion. I recognize that the article was an incredible portrayal of a family who knew nothing about the justice system and were victims of the justice system.

That must have been very difficult. Did it affect how crimes were covered?

It came at a great cost, but he took that talent that Dominique gave him and became a very well known crime reporter. He had the unique experience of having been in the judicial system, and also seeing firsthand of how the defense will try to portray the victim, usually women who were the most vulnerable, and slander their reputations. So whenever he wrote about OJ, he never forgot about Nicole, or whenever he wrote about Phil Spector, he wrote about Lana Clarkson.

Not long before the murder, you booked your first major film role in John Landis’ “American Werewolf in London,” which remains a beloved horror comedy. Why did you find it so destabilizing to put on the werewolf makeup every day?

I have a very different relationship to to horror. I go to horror cons — I’ve been to a few for “American Werewolf” — and so many people, kids, come up dressed as me, covered in blood with slashes across their throat and it’s a joyous experience for them to walk around looking like that. At the time, when I first saw Rick Baker apply that makeup, it just got more and more and more gruesome, and was also very time consuming. I would look at myself, it was so real — I would think, like “Oh, so that’s what I’m going to look like if I was violently murdered.”

I’ve always been very protective about my mother. My mother was ill and she’d been diagnosed (with multiple sclerosis) and she was just just starting to be in a wheelchair. My first thought was like, “What if my mother sees this, sees me torn to pieces on the screen, what effect will that have?” It was an entirely personal and surprising reaction. I was so thrilled to be in the movie. But I felt sort of haunted, I felt I felt like a part of me sort of died. I tried to describe it in the the book — I eventually got used to it.

Horror movies aside, you tell some very funny and very dark stories. Do you get that from your father?

Most certainly my father and my uncle had a dark Irish sense of humor, finding humor in the macabre. One of the earliest pranks my father played on me was when I was five, maybe six years old. I asked him, “When you die, can I keep this car and drive it?” and he said, “Kid, when I die, it’s all yours.” And then out of the blue, he faked a heart attack behind the wheel and said, “take the wheel kid, get us home.” I just thought it was hilarious. I just sort of knew he was kidding.

He grew up in an era of open casket funerals and pennies on the eyes and the casket in the living room for days at a time and Irish wakes, with the grownups drinking and reminiscing and laughing uproariously. So it was sort of a cultural gift or curse, however you want to look at it.

It was surprising to remember that Tim Burton came very close to directing “After Hours” instead of Martin Scorsese. What would that have looked like?

I think there would have been an “Edward Scissorhands” sort of element to it, both humor and darkness, and the hallways probably would have had bats fluttering around. It would have been an entirely different, but I’m sure fascinating movie.

I remember in Cannes in 1986, you weren’t able to get lettuce or milk because of Chernobyl. At the same time, fewer Americans went to the festival after the U.S. bombed Libya and Gaddafi threatened retaliation. What was your Cannes experience like with “After Hours”?

The bigger the star, the more likely it was you are going to be blown up, because Gaddafi had singled you out. But nothing was gonna keep me away from the Cannes Film Festival. The papers called me “the bravest American.” Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone didn’t go.

I found out later from the daughter of someone who was on the jury that I had won best actor. But they’d already given the award to Marty for Best Director. Then they went “wait a minute, the Americans didn’t come here this year, we have to give the actor award to a French actor.” But that’s how close I came.

Your friendship with Carrie Fisher, which started when you were teenagers, is an important part of the book. What was it like looking back at that relationship?

That was actually the most fun part to write about. All the people in my family came to life when I was writing it, but none of them actually made me laugh out loud while I was typing. When I wrote about Carrie, her voice was just so clear in my head, and her quips. That Mr. Toad’s wild ride (when Fisher taught Dunne to drive) and her driving up on people’s lawns and just our uproarious laughter and the silly musicals we’d make up when we talked to each other. They all just came roaring back.

What was her preferred method of communication? Did she call, or text? I know her book was “Postcards From the Edge,” but did she really write postcards?

I always had phone calls. The thing that she excelled in, though, over the years were postcards. If she went somewhere, anywhere around the world in her travels, she would just write one hilarious line after another and just send it off. Sometimes she would just go into a drugstore and just pull postcards of Los Angeles off the rack. They were like texts but had these one liners that just came off the top of her head that were hilarious.

I had a manila envelope just stuffed with these postcards and this onion-skin paper with typing on it. That came from when we were roommates, Carrie bought an IBM Selectric typewriter. And I’d be in my room reading, she’d be in her room reading. And all of a sudden I would hear typing in the living room. I’d know, “Okay, game on.” When she would go in her room, I’d go and add to the line she wrote. And we never said a word to each other. We just would speak through the typewriter, in these ridiculous characters. They were just kind of free association conversations of characters that we just came up with.

The book ends with the birth of your daughter in 1990, so it seems like you have a lot more you could include in another volume. For instance, you directed 1998’s “Practical Magic,” which is getting a sequel. What do you remember about the shoot on a Washington island?

We were on Friday Harbor, this beautiful, exquisite little island that I bet hasn’t changed since we were there. We did indeed all hang out. The coven of women were particularly close — so close that I learned something I didn’t realize was possible. I was told the that they all had their periods at the same time, which felt kind of witchy! But there were a lot of laughs. Sandy is hilarious. And, it’s been rumored that for the midnight margaritas “lime in the coconut” scene that I got everybody drunk on tequila. And that is absolutely true. It was a ridiculously fun night on the set.

Are you going to be involved with the sequel?

I’m going to be an executive producer on the picture. I’m sure a woman director will bring what she has to it. But I’m very curious to see it!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Source Agencies