I was late catching up to Jeff Nichols’ “The Bikeriders,” and though the film has gotten some good reviews, like Peter Debruge’s rave in Variety, it’s fair to say that the collective response to it has been mixed to muted. “The Bikeriders” hasn’t exactly set off a chain reaction of retro biker fever. It seems as if more than a few people don’t quite know what to make of it: a drama based on Danny Lyon’s 1968 black-and-white photography book, which captured the rough-riding lives of a Chicago motorcycle gang called the Outlaws (who, in the movie, become the Vandals), their exploits now presented, in Nichols’ film, in all their unvarnished bad-boy grit and glory. Personally, I loved the film, and came out of it with a sense of surprise — mostly at the fact it hasn’t been more robustly celebrated. But I think I understand why.

What, exactly, is “The Bikeriders” about? For starters, it’s about a specific time and place — the culture of biker clubs in the late ’60s to early ’70s. That’s a world that a lot of us may think we know from Hollywood biker sagas, but those movies, going back to the Marlon Brando film “The Wild One” (which looms large in “The Bikeriders”) and extending to such fabled counterculture genre flicks as “The Wild Angels” and “Hells Angels on Wheels,” are mostly the stuff of down-and-dirty B-movie folklore. They frame the delinquent side of biker culture as a kind of antiestablishment mythology. The “Mad Max” films, in a far more spectacular way, do the same thing, presenting biker gangs as a larger-and-life unruly force.

“The Bikeriders” may be the first drama about motorcycle gangs that feels entirely real (the interview portions of the film are framed as a documentary-in-the-making), and that’s what gives the movie its resonance. Its subject is not just the fatally glamorous leather-clad style of biker gangs, or their codes of freedom and loyalty; it is something deeper. “The Bikeriders,” I would argue, is a movie about primal male energy. And these days, that’s a subject that’s bound to provoke a conflicted response.

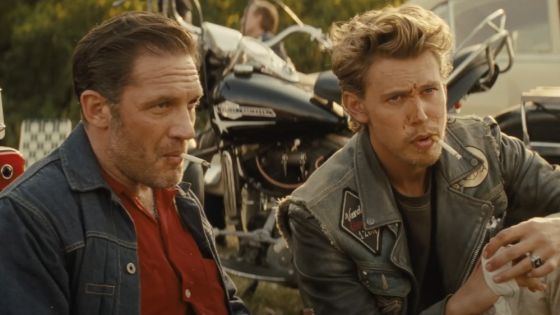

In the opening scene, Benny (Austin Butler), young and rakishly handsome, is seated alone in a bar, where he refuses a request by two patrons to take off his “colors” (the denim jacket with its antisocial insignia). He says he’d rather die than remove them — and the result is that he gets clobbered with a shovel. We think: Couldn’t he have just taken off the damn jacket?

But his attitude of hell-bent pride is central to the movie. The characters in “The Bikeriders” aren’t rootless (the gang’s founder and leader, played with mumble-mouthed neo-Brando charisma by Tom Hardy, has a steady job and a middle-class family), but they possess a restless spirit, an inchoate craving for violence and freedom, a need to feel like they’re living beyond rules. At the same time, they’re craving rules — or, at least, a code for living that doesn’t leave them feeling dead inside. Being part of the Vandals is what lets them breathe. Outside the gang, their aggression is something they don’t know what to do with. There’s no place for them to put it. And part of the film’s unresolved quality is that it’s capturing — about this gang, but also implicitly about the larger culture — a spirit of masculine identity that may feel like it’s struggling, more and more, to find a place to express itself.

Can the male energy we see on display in “The Bikeriders” be called toxic? Some of it is. But what makes the movie so seductive is its profound and poignant ambivalence. At times, it shows us men behaving badly (and it doesn’t glamorize those moments), but at other times it shows them acting with a reckless bravado that is glamorous. The movie is about the thin line that exists between those two states. The ambivalence, in the end, is really in us. We recognize the primal male mystique in “The Bikeriders” and the way that the film revels in it, but it’s also asking: How much is this what we want men to be?

Source Agencies