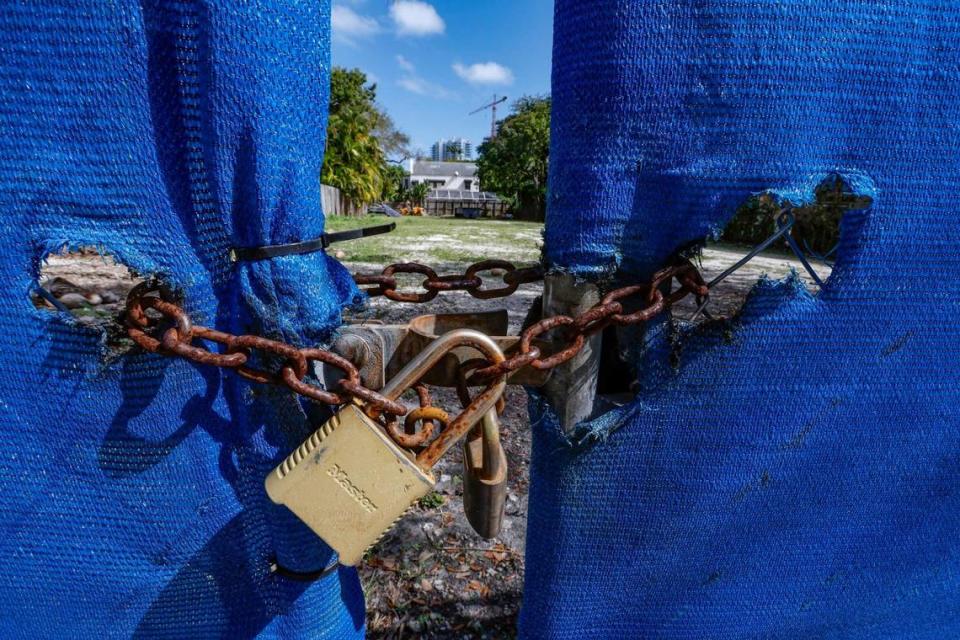

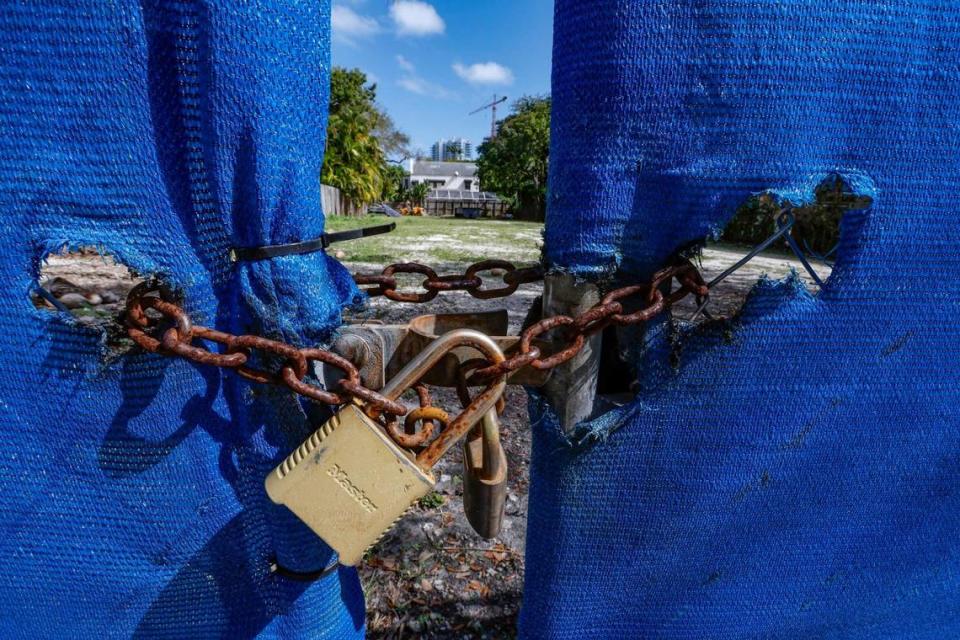

Take a walk down a block of Coconut Avenue and hear the ghostly silence. No children playing, no dogs barking, no neighbors grilling hamburgers.

A dozen immaculate townhouses remain uninhabited three years after most were sold or double sold, triple sold and, in one case, quadruple sold to buyers duped by developer Doug Cox into believing they were weeks away from closing on their dream homes.

From outside, the houses appear hollow. But all 12 are saturated with deceit, consternation and heartbreak.

They are for sale in Coconut Grove, one of the most desirable real estate markets in the country. Someone will buy.

Just not the people who were on the threshold of moving in.

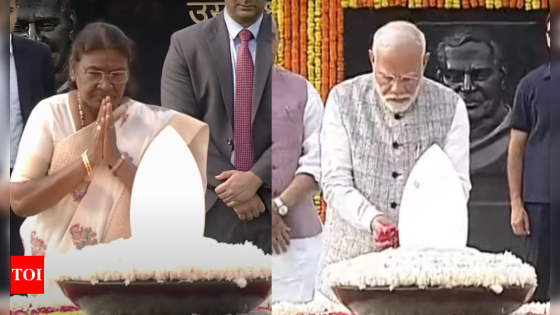

In a recent settlement of fraud accusations against Cox, 32 parties who are owed $34 million by the self-styled “King of Coconut Grove” have agreed to sign quitclaim deeds, relinquish any liens on the properties and surrender their goal of ownership.

They might recover 40 to 50 percent of the money they gave Cox if the 3,000- to 4,000-square-foot townhouses sell at their listed prices of $2.6 to $3.5 million.

“We lost, and the wrong people won,” said Kevin Ware, a Chicago transplant who expected to move into 2992 Coconut Ave. with his family in 2021 after putting down a $433,750 deposit on the $1.7 million townhouse.

Ware echoed other buyers who complain they were pressured into a settlement that favors deep-pocketed private lenders and investors who wanted to cash in on the booming Grove market touted by Cox. Miami’s oldest neighborhood is being transformed as its leafy canopy is chopped down to make room for supersized, cube-shaped houses.

.“Everyone always says Miami is a dirty, dishonest, double-dealing place. Now I’ve experienced it first hand,” Ware said. “I love Miami, and I’m not leaving, but, holy crap, the corruption is unbelievable.”

Closing dates kept getting pushed back

Ware and a few other original buyers grew suspicious three years ago when Cox kept postponing their closing dates as housing prices skyrocketed during the COVID pandemic influx of Miami newcomers. The City of Miami Building Department, which allowed Cox to keep building through a Stop Work order, said it couldn’t help them. They were determined to warn potential buyers and halt what they described as a Ponzi scheme Cox was running on his 27 Grove properties, collecting larger and larger deposits as the townhouses and prime lots increased in value.

In total, Cox amassed about $70 million. It’s all gone.

Sixteen months after a Miami Herald investigation compelled his former business partner to file an emergency motion for a court-appointed receiver to seize control of Cox’s companies and properties, the case has not been resolved as victims of the alleged fraud had hoped. Some $20 million remains unaccounted for. They won’t get their finished or promised homes, or the savings they invested back when mortgage rates were 2 percent and the houses were selling for $1.2 to $1.8 million — unless they can afford to pay twice the original price.

READ MORE: They bought their dream homes from the ‘King of Coconut Grove.’ They still can’t move in

“Development in Miami is a magnet for crazy people, and private equity lenders are poisoning the landscape, yet the law favors them over homebuyers who want a piece of the American dream,” said Alexandra Cardoso, an early buyer who placed a $155,000 deposit on her Coconut Avenue townhouse in 2018, planning to move her mother in, and give her daughter a bedroom of her own during her high school years. “The real estate industry needs to be purged and reformed so future generations won’t be cheated like we were.”

‘I’m not dropping this fight’

Michael Coyne is the only creditor who refused to sign the settlement agreement written by receiver Alan Fine, a retired Miami-Dade circuit court judge, and his counsel Paul Singerman, and mediated by retired Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Michael Hanzman, who oversaw the Surfside condo collapse case that was settled for $1.1 billion.

Coyne, an investment banker from New York, and his wife Oksana, a nurse, had planned to move into their new $1.6 million townhouse at 2978 Coconut Ave. in 2021, before their twin daughters were born, with their son and Oksana’s parents, who are from Ukraine. But since they put down their $487,000 deposit, they have lived in seven different rentals, with most of their belongings in storage.

“I’m not dropping this fight or letting these scumbags off the hook,” said Coyne, who objected to the settlement at a hearing before Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Thomas Rebull. “Nothing was accomplished by the receiver, who has given priority to predatory lenders and treated this like a bankruptcy, which it is not, and acted as a real estate agent, which he is not.

“Everyone is being paid handsomely, billing by the hour, for not cleaning up this mess and not holding anyone accountable. So far the victims, regarded as a nuisance, have gotten nothing. Nothing.”

Receiver: Untangled a mess

Fine and Singerman disagree, saying in an interview with the Herald they are “immensely proud” of the “relentless work” they have dedicated to untangling the strands of a case that began in May 2023 with a negative balance in one of Cox’s bank accounts, a $33 million mortgage by the major lender running a 24.5 percent interest rate tab, a growing list of claimants who suddenly discovered they’d been scammed, a “toxic” relationship with City of Miami building inspectors, uninsured houses with expired permits on the cusp of hurricane season, and little cooperation from Cox and his wife, Nicole Pearl, a Miami lawyer who wrote the purchase contracts, listed the properties and did the bookkeeping.

In decades of handling similar cases, Fine and Singerman said victims often recover only 5 to 10 percent of what they lost. Rarely does anyone emerge whole, lawyers’ fees spiral as litigation drags on and the pot of assets diminishes.

“I have always been more empathetic to the buyers, who were making a life decision, than to the lenders, who were making a financial decision,” said Fine, who estimated that the receivership has cost $2.4 million so far. He charges $750 per hour. “That doesn’t give buyers a leg up legally over secured creditors. We were bound by law in our decisions, not sympathy.”

Houses still lack occupancy certificates

But, in some respects, Coyne is correct. The case against Cox and Pearl is right back where it started.

The houses built by Cox with various code violations still don’t have certificates of occupancy from the City of Miami building department, and until they do, no one can live in them. The same engineering firm employed by Cox that couldn’t get inspections approved — MEP Consulting Engineers and its president, Katrina Meneses — is on the job, hired by Fine. The same real estate agent employed by Cox — Randi Connell — is the listing agent, selected by Fine.

Cox’s former business partner — Phillip Sylvester — bought the 12 undeveloped properties that he had owned previously in a joint venture with Cox. Sylvester is owed an additional $13.5 million from an $18 million loan he made to the receivership, and that loan is costing $5,000 per day in interest. Pearl still has her law license and real estate license and is believed to be living in the New Jersey area.

And Cox is back in Coconut Grove — if he ever left — where he’s been observed at the work site of one of his old properties on Bird Road — an incomplete condo project he gave back to Fuse Group after it lent him $4.7 million to buy it.

Cox, 53, is often seen driving around the neighborhood in a Jeep Gladiator outfitted with custom rims. He tells people he’s homeless and has been living in his car since he and Pearl, parents of three young children, were evicted last year from the house they rented on Inagua Avenue for $12,000 a month.

What else hasn’t changed? It isn’t clear whether authorities will charge Cox and Pearl with a crime. A few original buyers have met and filed complaints with the FBI, the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office, City of Miami police and the Florida Bar. Their meetings last year with building department officials and with Miami Mayor Francis Suarez — to whom Cox made $200,000 in campaign contributions — went nowhere.

Ware was walking his dog recently when Cox drove by, waved and pulled over.

“Doug smiled and said, ‘See, I’m not in jail yet!’” Ware said. “I told him, ‘You will be soon enough, and I hate your guts.’ Then we had a surprisingly civil chat.”

Cox, who has declined to answer questions from the Herald, even showed up at one of the open houses on Coconut Avenue last month, according to Connell. She worked for Cox and Pearl for less than a year and quit in 2022 when she concluded “the whole situation with Doug and Nicole was nuts.”

‘Not a fire sale’

Connell, who works for longtime Grove Realtor Riley Smith, said she’s received some “ridiculously low offers, but this is not a fire sale.”

Billionaire Ken Griffin, the Citadel founder who is moving the headquarters of his financial empire to Miami from Chicago, considered buying all the townhouses but the bulk deal fell through.

Connell said she has priced the houses at 8 to 9 percent below market value, at $840-850 per square foot vs. $925 per square foot, in a cooling market where interest rates remain high. The houses are advertised as “new construction (2021-2022),” acknowledging they are no longer new.

“I’m trying to change the negative narrative on these high-quality houses,” she said. “My heart goes out to the buyers who put down their life savings. I was dished the same lies. I had sold two of Doug’s undeveloped lots and two townhouses that my clients lost. I’m committed to selling them for as much as possible so that as much money as possible goes back to the buyers. As a working mom of two daughters, I feel for those families 100 percent.”

Connell, who hosted an open house at 2955 Coconut Ave. over the weekend, said she’s sensed wariness from prospective buyers.

“They’ve asked, ‘Are people going to show up at the door and take the house from us?’” she said. “We want to assure them the title will be clear.”

That is, unless Cox interferes. Although all claimants except Coyne have signed releases and agreed not to sue, Cox and Pearl have not. Sylvester is having trouble getting title insurance on the 12 vacant lots he purchased from the receivership for $16.5 million because Cox hasn’t given up his claim to them.

Connell denies she knew Cox was stalling multiple depositors when she worked for him. Buyers such as Alan Lombardi are outraged that Fine selected Connell. Lombardi confronted Connell in May 2022 when she was showing the $1.3 million townhouse he bought in 2020 with a $260,000 deposit, and expected to move into with his partner and newborn twins.

“It’s absurd that of all the real estate agents in Miami, Fine picked Connell,” said Lombardi, who is himself an agent.

Connell said she was merely showing Lombardi’s unit as a model.

“Doug was charming. He was convincing. You felt you could trust him,” Connell said. “But he always had an excuse for the delays: ‘Just let me do my thing, I’ve got inside connections with the city.’”

Buyers are angry that Fine chose real estate broker Vivian Dimond last year to prepare and market the houses. Dimond charges $295 per hour and has earned more than $575,000 since May 2023 from the receivership. Her chief assignment was to obtain certificates of occupancy. Fine, who defended choosing both Dimond and Connell based on their experience, is still waiting for the COs.

“It’s been an incredible waste of time and money,” Cardoso said. “When the receiver was appointed and said he could secure the COs in six weeks, we were optimistic Doug would be forced to finish inspections, our contracts would be honored and we’d finally get our houses. We were even willing to negotiate a higher price for them.

“But the receiver wanted to wait and put them on the market. More than a year has passed. Buyers are steering clear of those houses now because they don’t have COs and the market is soft. They’ll be lucky to get anything close to what they’re asking.”

Host of building code issues

Building code problems were more convoluted than anticipated, and city inspectors are being extra cautious given the scrutiny, Fine and Singerman said. One example: Cox built six 3-story townhouses on Coconut Avenue but only submitted 2-story plans.

“We are currently working on a backyard flood drainage solution,” Fine said. “The plans called for berms. We tried to convince the city that berms are unsafe. The city said build the berms. Then the city came out and said this is stupid, get rid of the berms. The city is now granting us daily meetings.”

“At the outset we assumed it would take a couple months at most,’’ Fine added. “We saw the same thing that convinced buyers to sign —beautiful ready-to-move-in townhouses that looked finished! Little did we know we were seeing the tip of the iceberg.”

Fine has managed to sell three houses from the Cox portfolio, including the townhouse at 3167 Shipping Ave. that Cox planned to reside in. That four-bedroom, four-and-a-half bathroom unit and the adjacent one at 3157 Shipping Ave. were sold “as is” to James Rosenthal for $5.8 million ($698 per square foot) after being listed for $7 million ($843 per square foot).

The house at 3157 had been under contract to two different buyers, unbeknownst to them. Rosenthal was the second, and gave Cox a $725,387.64 deposit two years ago.

Rosenthal, who lives in New York City, will move in after he obtains a CO. He didn’t say what he will do with the house of would-be neighbor Cox. But he could flip it and make a tidy profit.

The house at 4010 Park Ave. in the South Grove, nicknamed the “House of Rumors” by neighbors who have watched it being built for a succession of buyers since 2016, sold “as is” for $3.2 million. Fine hoped to get $4 million but the house has numerous flaws, including improperly placed windows and showers.

Original buyers contend the sales of the Shipping and Park houses and the 12 undeveloped lots to Sylvester were made at discounted prices — discounts they wanted on their houses but were not offered.

Solomon-like dilemma

“Not everybody is made whole. We get it,” Ware said. “But it’s a slap in the face that after years of suffering, instead of negotiating with us or entertaining other ideas on how to divvy up the proceeds, with the professional lenders receiving a lesser percentage for making bad loans to Cox, they scare and bully us into giving up.”

The sales offers accepted were the highest ones, Fine and Singerman said. As for negotiating a lower price for certain buyers, Fine would have been faced with a Solomon-like dilemma.

“On homes sold to multiple buyers, which one would get the opportunity to buy and how do we explain that to the other depositors?” Singerman said. “If we give a discount, the other victims don’t recover as much money.”

The settlement was structured so that lender DC Fund, which had eight properties as collateral, is defined as a secured creditor and is entitled first to full reimbursement of its $1.9 million loan to Cox. DC Fund associates are in the merchant cash advance business. The other investors and buyers who put down deposits will be treated equally and reimbursed from the sales proceeds pro rata.

Buyers’ lawyers argued in court that the case should have been managed as an equitable proceeding and not as a semi-bankruptcy. That way, the buyers, as unsecured creditors, would not be lower in the pecking order to lenders, the secured creditors.

Judge Rebull rejected the argument.

Most buyers signed contracts with Cox in which they waived various rights — including the right to sue Cox for not delivering the houses. They allowed Cox to use their deposits as he wished rather than place them in escrow, and agreed to be subordinate to lenders. Contracts with developers are typically one-sided.

READ MORE: Real estate contracts tend to favor developers. What homebuyers should watch out for

“Receivers borrow a great deal of their law from bankruptcy cases,” Singerman said. “You have a statutory priority distribution scheme. The fundamental missions of receiver or trustee are the same.

“As for high-risk, high-interest loans, they are not illegal and that’s why lenders sign contracts with collateral. You can view lenders as predatory — or as the fertilizer for an entrepreneur who couldn’t get a bank loan.”

Coyne was disappointed by the outcome, which he believes was preordained before the mediation session with Hanzman was held.

“Shame on the receiver and shame on the court,” Coyne said. “They relegated innocent buyers to the bottom. They had a choice under the law and chose the easy way out.”

Sylvester called the settlement fair. He’s owed $6 million he lost to Cox and $13.5 million of the $18 million he lent to the receivership in December to pay off Altamar Financial Group. Altamar lent Cox $33 million in 2019 for construction, gave Cox eight extensions despite Cox’s failure to close sales and only foreclosed after the Herald article was published.

Sylvester’s $16.5 million purchase of the 12 undeveloped lots plus his $18 million loan enabled Fine to cut a deal with Altamar in a 15-hour mediation with Hanzman during which Fine “laid out our usury and unclean hands arguments against Altamar.”

Altamar, which was claiming $22,000 in interest per day, exited the case. But the accruing interest on Sylvester’s loan adds urgency to Fine’s aim of selling the townhouses at maximum value.

“It’s not over. But we felt mediation was an effective way to move forward and stop the hemorrhaging of legal fees,” said Sylvester, who says he was betrayed by Cox and has devoted the past year to rectifying the wrongs committed by Cox and Pearl. “Nobody walked out satisfied. It’s a tough situation. The receiver believes it was an equitable outcome.”

Who is owed money

The 32 settlement claims range from Sylvester’s $6,113,653 to the $150,000 deposit of early buyers. A physician and her husband put down $420,000. The buyer of a coveted Secoffee Street lot, where Cox promised to build a sleek new house with an oak-shaded atrium, put down $1.4 million. A transplant from Southern California expecting a townhouse to rise on an overgrown Gifford Lane lot put down $671,250.

Chris Paciello, the former South Beach nightclub impresario, was persuaded by Cox to sign five contracts and hand over $2.3 million, according to court filings. Paciello, aka Christian Ludwigsen, is a gym owner and real estate investor today but was a celebrity when he partied with Madonna, Sofia Vergara and Jennifer Lopez in the 1990s.

Paciello, a former FBI informant on his New York mafia contacts, pleaded guilty to racketeering in 2000 and served six years in prison. Paciello’s business partner Mio Danilovic is claiming $1.2 million as a Cox investor who got conned.

In Cox’s alleged juggling act, 2960 Coconut Ave. was the house that kept on giving. Four different people signed purchase contracts for it and paid Cox deposits ranging from $500,000 to $1.5 million.

LV Lending is claiming $5.2 million. An investor called Cocogrove Phase 2 agreed to give up its $3 million claim. Both companies alleged in lawsuits they got conned by Cox and Pearl, who impersonated an Altamar loan manager to vouch for their creditworthiness.

“The fraud was remarkable and stunning,” Fine said. “There were falsified documents and the subterfuge of phone calls from people who didn’t exist.”

Fine and Singerman and the forensic accounting firm they hired have not found any money hidden away by Cox and Pearl. The jumbled records they sorted through show some of the $70 million the couple collected was spent in a vicious cycle of taking out loans to repay other loans at exorbitant rates. Gross mismanagement deepened the hole.

Court files reveal a glimpse of Cox’s scramble for quick cash. There’s an American Express bill for $870,087. Among his loans: $18,570 received from and $30,350 paid to Last Chance Funding; $114,537 in and $329,144 out to On Deck Capital, and $47,485 in and $77,680 out to High Speed Capital.

“This was no sophisticated Oceans 11 heist,” Ware said. “It was greed, pure and simple.”

Source Agencies