Dick Asher, a veteran music-business executive who was president of PolyGram and Columbia Records and worked with artists ranging from Bruce Springsteen, Michael Jackson and Bon Jovi to Bob Dylan, has died, his family confirms to Variety. His son Jeffrey confirmed that Asher died peacefully at home in Boca Raton, Fla. on Tuesday; he was 92.

Renowned for his upstanding business practices over his four-decade career in music — although as a former Marine, his disciplined demeanor was sometimes at odds with the mores of the industry’s most freewheeling era — Asher is best known for his efforts during the 1980s to battle the powerful group of independent promoters, known as “The Network,” that came to dominate radio airplay via payola and other unsavory, at times illegal efforts, as depicted in Frederic Dannen’s 1990 book “Hit Men.”

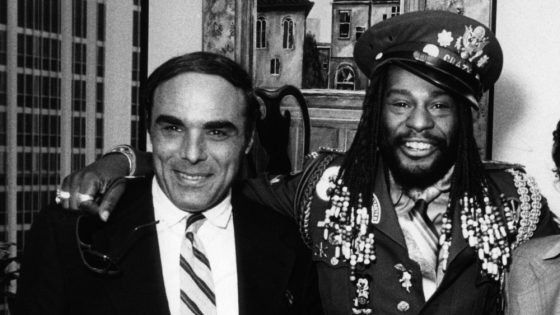

A native of New York City, Asher — pictured above, left, with funk legend George Clinton during the 1980s — was born in 1932 and served in the Marine Corps before graduating from Tufts University and Cornell Law School and taking a job as a corporate lawyer. He joined CBS Records (now Sony Music) in the mid-1960s as VP of business affairs.

During that period, he was one of the very few people to meet with Bob Dylan during the singer’s convalescence from a reportedly near-fatal motorcycle accident in 1966. Asher drove to Woodstock, New York, to negotiate Dylan’s contract renewal and, upon his return to the CBS offices, was met with astonishment by his fellow executives, as the singer had been in near-total seclusion. Asher said he’d asked Dylan what his new music was like and said the singer replied, “It’s a little further on down the road,” presumably referring to the songs from the now-legendary “Basement Tapes” with the Band and his “John Wesley Harding” album. (Years later, Asher would spar with Dylan over the latter’s decision to record Christian-themed music during the late 1970s.)

After a brief stint at Capitol Records, Asher returned to CBS in 1971 to work with Clive Davis at Columbia Records and was soon sent to London to turn around the company’s flagging U.K. division, which he did in short order and was promoted to head of international. In the late 1970s, as the music industry went into a recession due to the rapid decline of disco, Asher was named deputy president of the label, where he revived the company’s bottom line, albeit largely due to layoffs.

As detailed at length in “Hit Men,” during the same period Asher began to tackle the growing influence of independent radio “pluggers,” who had gained a monopoly on airplay and were charging labels exorbitant fees that reached into the millions each year — and in some cases were connected to organized crime. When Asher attempted to take Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1” — from “The Wall,” the blockbuster new album by one of the biggest groups in the world — without using indies, no major radio station in Los Angeles and many other markets would play the song. But when he resumed paying indies, both the single and the album shot to No. 1 and remained there for four months.

Asher sought to take on the indies but sparred with Columbia’s infamously volatile boss, Walter Yetnikoff. The standoff continued over the next several years — even as CBS Records attained record revenues thanks to smash albums by Jackson, Springsteen and others — until Asher was forced out of the company by Yetnikoff and CEO Thomas Wyman in 1983. “The Network” was ultimately brought down after Congressional hearings in the mid-1980s, by which time Asher had moved on to senior roles at Warner Communications and, in October 1985, president/CEO of PolyGram Records, which was about to release two of the biggest albums of the decade with Bon Jovi’s “Slippery When Wet” and Def Leppard’s “Hysteria,” along with hits by Cameo, John Mellencamp, Scorpions, Cinderella and many others. Despite the company’s success, Asher left the company in 1990 after a contractual dispute with the company’s owners.

After leaving PolyGram, he returned to law practice and consulted for several artists and companies before becoming an original director for Electronic Arts software, a post he retained for the next 24 years. He relocated to Florida in the 1990s and later was an affiliate professor of commercial music at Florida Atlantic University, where he helped launch the school’s recording studio among other efforts.

Asher is survived by his wife, Sheila, and son, Jeffrey (a daughter and second son are deceased), four grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

Source Agencies