Luca Guadagnino‘s adaptation of the William S. Burroughs novella “Queer,” which premieres Tuesday in competition at the Venice Film Festival, is his most personal film yet — and one that he’s been dreaming of making for many years.

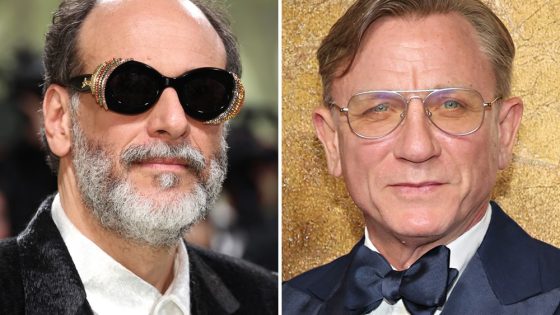

The stars aligned when producer Lorenzo Mieli and Fremantle’s head of literary acquisitions Raffaella de Angelis were able to get the book rights and Guadagnino rapidly paired up again with “Challengers” writer Justin Kuritzkes. Then, CAA chief exec Bryan Lourd brought Daniel Craig on board to play the renowned counterculture author’s alter ego, Lee, an outcast American expat who lives in Mexico, and “Outer Banks” star Drew Starkey was cast as a younger man with whom he becomes madly infatuated.

From the director of “Call Me by Your Name,” the film features intimate love scenes between the two men that will certainly make it one of the buzziest indie movies of the year. Venice Film Festival artistic director Alberto Barbera has called the film’s very explicit erotic sequences “a sign of great courage in an era in which these behaviors are still rejected by a significant part of the audience.” A24 will release “Queer” in U.S. theaters later this year.

Below, Guadagnino speaks with Variety about his love for “Queer” and his quest to make Burroughs’ novel universal.

You read “Queer” at 17. What struck you about the book?

As a 17 year old, I knew my sexual identity but was also discovering it. To read a book that was so candid about homoerotic love played a big part. But beyond that, it was Burroughs’ language and imagination. He describes, for example, this idea of the translucent body that projects out of the physical body in search of the body of the loved one. This is an image that had a huge impact on me, and that’s in the film.

Cut to many years later, and your film adaptation of “Queer” is about to premiere at Venice. Talk to me about the decisions you and Justin Kuritzkes made in adapting this short novel by Burroughs, which I believe was unfinished?

It is unfinished. Justin can be more precise about this, but I remember that we said, “What is unfinished, we want to try to finish.” And in doing that, we have to understand why it was unfinished and how Burroughs would have finished it. In the process, we bumped into the wonderful Oliver Harris, who is the greatest William Burroughs scholar, and was so helpful and informative. What we discovered is that William Burroughs — who created this imagery that is dry, witty, sarcastic and perverted, this gentlemen of deconstruction and cynicism and apocalypse — in fact was a very tender man, a very shy man. And that aspect kind of cultivated the idea of love that we glimpsed throughout the novel.

Tell me more about the adaptation process.

The novel for us was never a novel about unrequited love, or an older gentleman trying to convince a younger one, who is straight, to love him back. We felt that there was something in this book that was more about the idea of connection and disconnection and, more importantly, repression and compression. I think both me and Justin share a passion for seduction in that we like the idea of making people connect with what they see, and also be entertained by what they see. So for us, the idea that this could become not only a great love story, but possibly the ultimate love story — and a very universal one — was irresistible. What is irresistible is the idea that you take Burroughs, and you make him universal.

How did you get Daniel Craig on board?

Once Justin wrote the script, I spoke to my agent, the great Bryan Lourd, and I gave it to him. And Bryan, who knew the book by heart, was really so sharp in understanding what we were trying to do. And we were chatting about who could be the incarnation [of Burroughs] and I said, “I don’t know. I think it should be someone iconic.” And he said, “What about Daniel Craig?” I said, “Well, I thought about him, but I don’t know. I would never dare to ask.” He goes like, “Why? He would love that.” And I said “Wow! Would you give it to him?” He said, “Sure.” He gave the script to Daniel, and Daniel and I were on the phone a week later. Then, a week passed, and he was in the movie.

Daniel is this incredible icon that has drawn audiences all over the world and will do that forever through James Bond. But of course, for me, Daniel has also been George Dyer in [John Maybury’s] “Love Is the Devil,” where he plays Francis Bacon’s lover. And of course, he is, honestly, one of the great actors of his generation: so subtle, so profound and yet so beautifully universal. So when he said, “Yeah, I’m up for it, and I’m up for anything that is required for me to be doing in this movie,” I really felt like: “You know what? I’m a lucky guy.”

Venice Film Festival director Alberto Barbera has pointed out Craig’s full-on sex scenes in “Queer,” whereas you drew some criticism for lack of any explicit sex in “Call Me by Your Name.” What’s changed?

I never really clicked with the negative comments about the lack of sex on-screen in “Call Me by Your Name.” I thought those were salacious comments by superficial people. And it pains me that a few of these comments come from people that I worship very dearly. This idea that there was a sort of negation of gay sex in the film, it’s ludicrous. When you make a movie, the only thing that rules the movie is the movie itself. And anyone who wants to put an agenda on top of the movie itself is stupid.

In “Call Me by Your Name,” you had to leave the curtain closed for the lovers to explore their idyll. In the case of “Queer,” this is a movie about the fever dream of connection and disconnection. And the only way we can really communicate the depths of their connection, and the dramatic denial inhabiting them, is that you have to see their interaction. From the way they travel together; the way they drink together; the way they fuck together; to the way they are apart and together. It’s integral to this idea of connection and disconnection, or as Burroughs would say, disembodiment.

Talk to me about casting Drew Starkey.

Drew Starkey is another great moment of my career. I was in London for “Bones and All” and my friend Peter Spears, with whom I produced “Call Me by Your Name,” said to me, “Hey, I’m casting a movie, and I bumped into this self-tape from this young guy. Would you like to see it because I think this is someone you should consider for Allerton?” And he shows me this tape, which has nothing to do with “Queer” and I see this guy. I said, “Whoa. Arresting, incredible acting.” Then we went through the process, and we saw 300 people, and every 50, I would say to Daniel: “I think he is still the best. Yeah, but let’s keep going.” So we kept going. And after the 300th, I said: “I think he’s still the best,” and he goes like “Yes, there is nobody better than him.”

In “Queer,” Drew became a young man of the ’50s. The way he moves his limbs, the pose, everything, his gestures are so incredibly profoundly 1950s. And to see a young man from the present becoming a young men from that era, with all the articulacy of that time is fantastic.

What’s been key to bringing this story to the screen in a way that is universal? It seems to me you were able to shed some of the heavy baggage from the Beatnik era.

Beat Generation is about youthfulness. It’s about a revolution in the making, even if it’s sometimes a sort of harsh revolution. It’s about burning down the house, and that has been the way in which every generation has behaved toward the older generation. So it’s important that when you deal with the Beats, you keep that flame very much alive. Because if you make a period drama that’s set in the ’50s, and you start to use it as an example of, let’s say, high literature that has to be arthouse moviemaking, you are immediately making huge missteps. Because you are really betraying the spirit of what the Beat Generation is. That’s why my beloved [Bernardo] Bertolucci, when he adapted “The Sheltering Sky” by Paul Bowles — who was peripheral to the Beats, but friends with them — he opted for the ultimate melodrama, another popular genre. He wasn’t trying to make a cerebral movie.

So we wanted it to be very picaresque, very funny, very romantic and very revolutionary in spirit. But revolutionary in the sense of being young and dreaming of doing something new for the first time.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Source Agencies