On a foggy spring afternoon in Calais, President Mitterrand of France and Queen Elizabeth II fastened their seatbelts in the royal Rolls-Royce. Just over half an hour later, they arrived in Folkestone.

“To rejoin what nature separated some 40 million years ago has been a recurring dream of statesmen and engineers for several centuries,” said the Queen, after disembarking the first ever vehicle shuttle through the Channel Tunnel.

It would be another six months before the first Eurostar passenger train would depart from London Waterloo to Paris (on November 14), but the opening of the Channel Tunnel on May 6 1994 was a symbolic moment in British history. It represented the end of British insularity. It was the embodiment of post-war European peace. Or it was a white elephant, doomed for failure – depending on who you were asking.

Over three decades, nearly 500 million people and more than 100 million vehicles have passed beneath the waters of the English Channel on LeShuttle (formerly Eurotunnel), and more than 200 million Eurostar passengers have made the crossing by train. The tunnel is a popular way of getting to Paris or Amsterdam – partly due to the speed and convenience, but for the comfort, too.

President Mitterand seemed to agree: “I’ve had a very comfortable journey in a very comfortable car, and it just happened to be yours, Ma’am,” he said to Queen Elizabeth II on that May afternoon 30 years ago. The journey for the Channel Tunnel, however, hasn’t always been so comfortable, and in 2024 the companies that operate on these subsea lines face greater challenges than ever before.

It all started with Napoleon

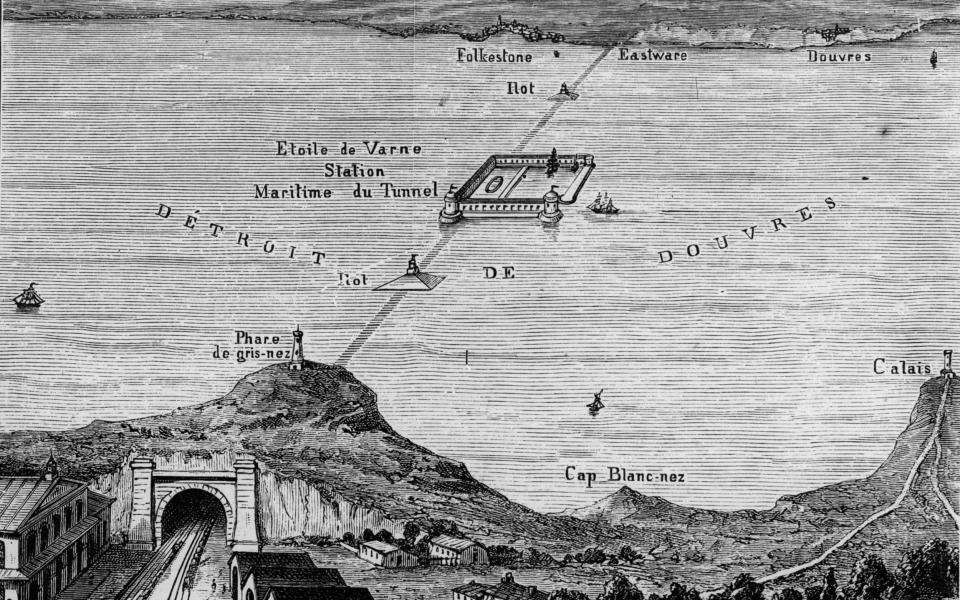

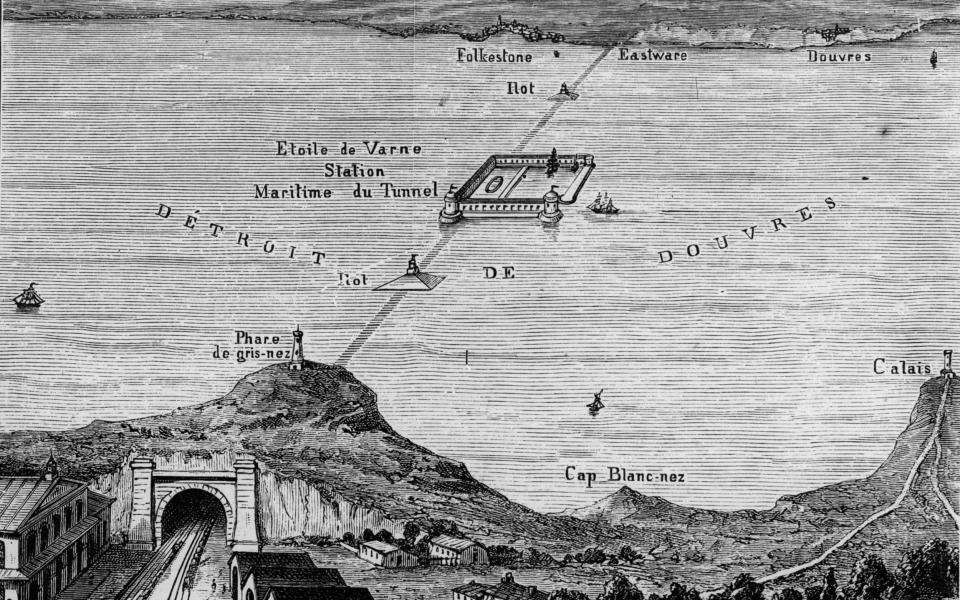

Plans for a Channel Tunnel were first drawn up by a French engineer, Albert Mathieu-Favier, who in 1802 presented blueprints to Napoleon Bonaparte before they were exhibited in the galleries of Paris. The tunnel would be illuminated by oil lamps, with horse-drawn coaches transporting passengers between the two countries.

Reactions to the idea were mixed, particularly on the northern side of the Channel. Lord Palmerston later dismissed it on the grounds that “it would shorten a distance we already find too short” and a British army general said it would “open out a road to the invader into England” – although Queen Victoria, who suffered terrible seasickness, was said to have supported the idea.

Throughout the 19th century, numerous surveys and geological studies tested the viability of the tunnel, and in 1875 an Act of Parliament authorised the Channel Tunnel Company to begin trials – inspired, perhaps, by the success of Brunel’s Thames Tunnel, which opened in 1843. Engineers got as far as boring holes at Folkestone, but none came close to reaching the coast of Calais. Security concerns remained a big worry at the time, with an 1882 committee concluding: “There should be means of closing the tunnel by a portcullis, and also of discharging irrespirable gases into it.”

In the early 20th century, Winston Churchill was an advocate, writing an essay for the Daily Mail in 1936 entitled “Why Not a Channel Tunnel?”, although during a time of great instability in Europe, fears of opening the doors to foreign armies continued to prevent any serious progress.

The notion of a fixed link between England and France resurfaced in 1979 after Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government came to power, although her dream of driving across the Channel (whether through a tunnel or along a bridge) never gained traction. A rail connection it was. Thatcher had no desire for the government to fund the project, so along with her French counterparts plans were drawn up for a privately funded triple tunnel: one to shuttle vehicles, one for passenger trains, plus a third service tunnel.

Work began in 1987 and in December 1990 French and British engineers met, deep under the seabed, as they hacked through the final few inches of chalk. The historic handshake was captured on television. Three-and-a-half years after that, at a total cost of £4.65 billion, the Channel Tunnel opened. In a way, Britain ceased to be an island on May 6 1994.

Dropped destinations and half-empty trains

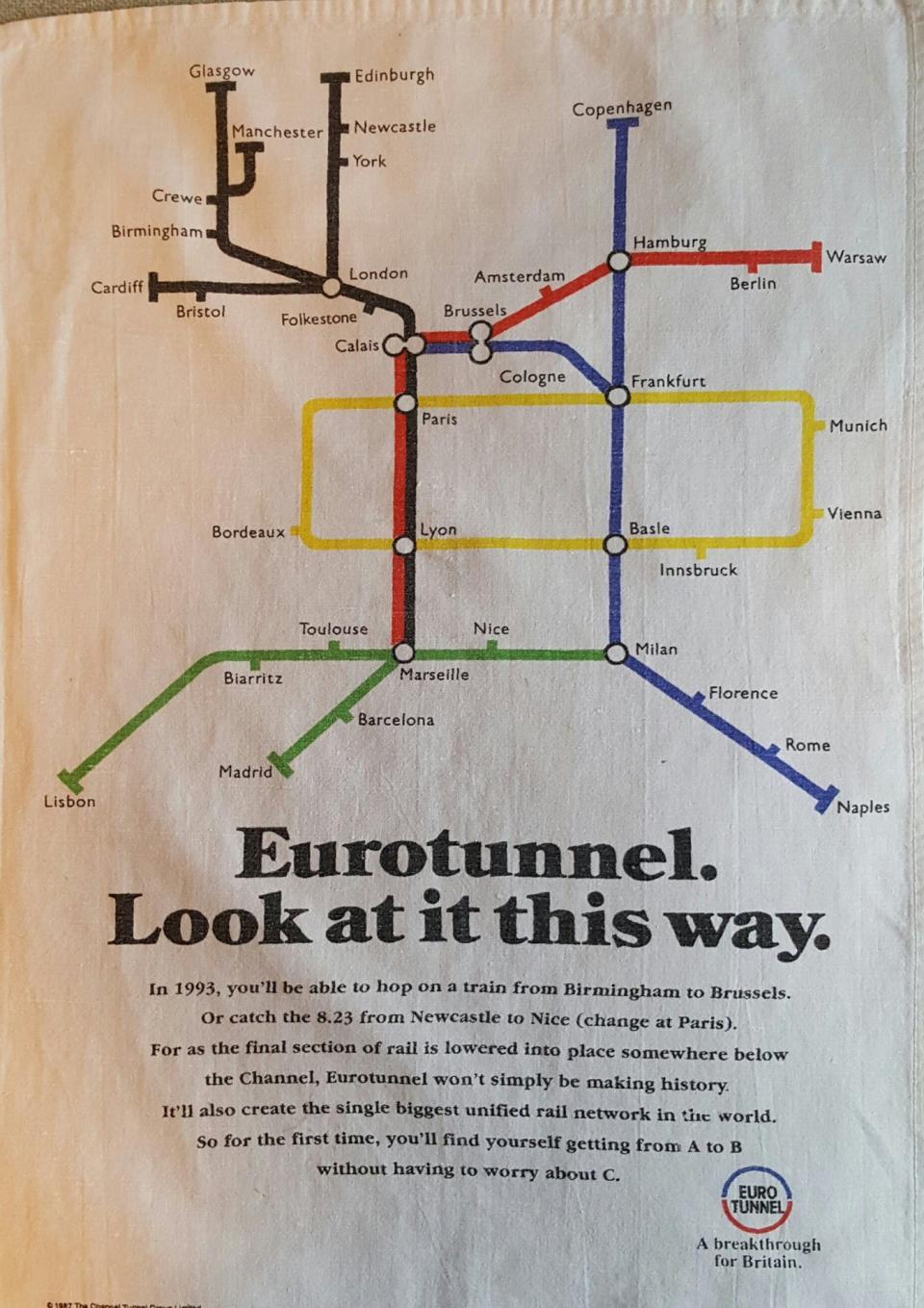

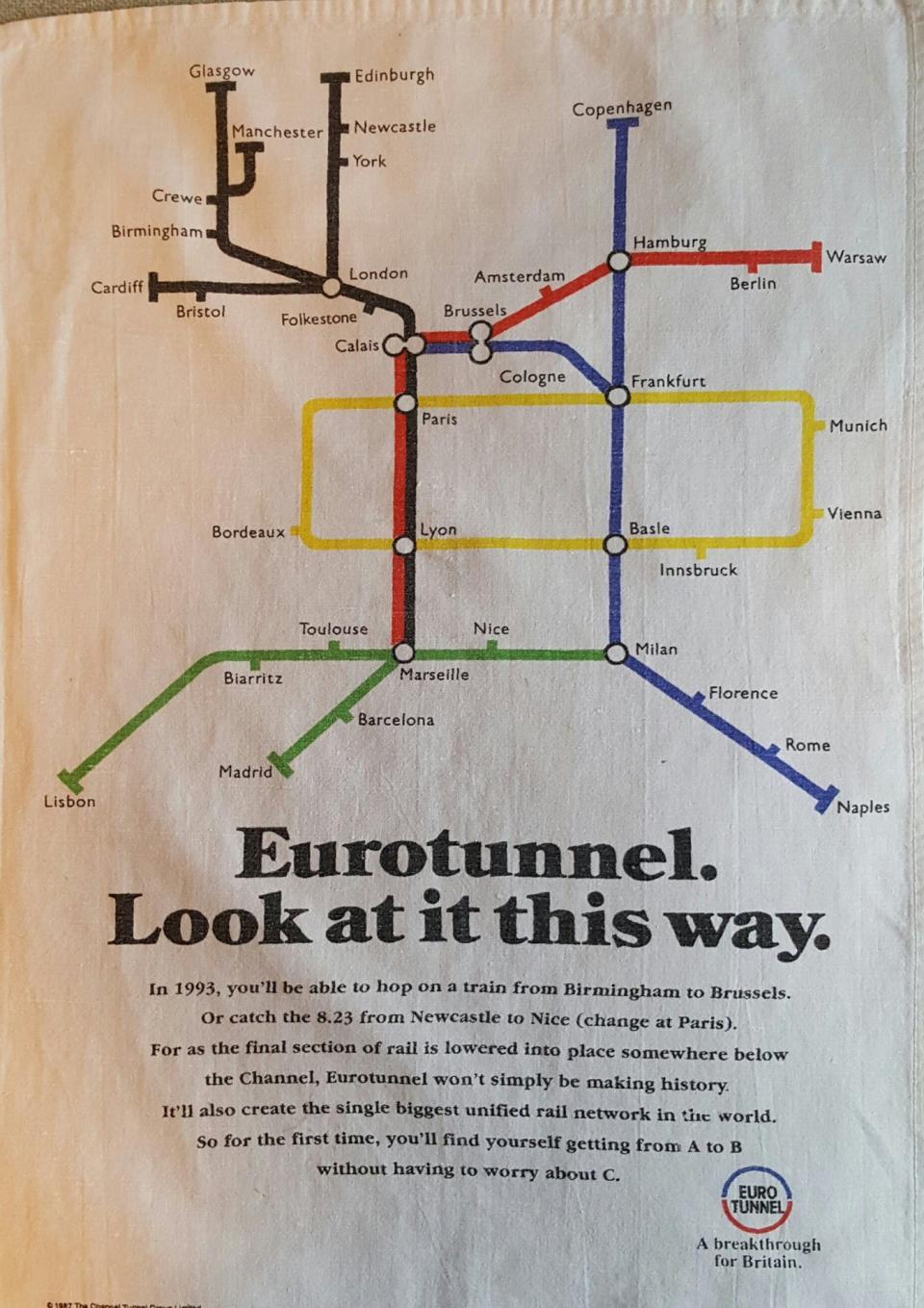

There was an advert, published by Eurotunnel in 1987, which said: “Eurotunnel. Look at it this way.” It showed a map that resembled the London Underground, with lines connecting Glasgow to Marseille, Cardiff to Calais, and offshoots stretching to dozens of European destinations including Naples, Lisbon and Copenhagen.

“You’ll be able to hop on a train from Birmingham to Brussels. Or catch the 8.23 from Newcastle to Nice (change at Paris),” the poster promised, adding: “For the first time, you’ll find yourself getting from A to B without having to worry about C.”

In the early days of the Channel Tunnel, there were high hopes of direct, high-speed rail connections beyond London to Paris. Some of these did materialise. Today, you can travel direct from St Pancras International (which replaced Waterloo in 2007) to Paris, Lille, Brussels, Rotterdam and Amsterdam, although the Dutch return legs will be suspended for six months from June 2024 while work is carried out to expand Amsterdam Centraal’s terminal, meaning passengers will have to change at Brussels.

But this is a reduced map. Passengers have, in recent times, been able to travel direct from London – plus the Kent stations of Ashford and Ebbsfleet (both out of service since 2020) – to Lyon (axed in 2018); Calais-Fréthun, Avignon and Marseille (axed in 2020); 16 ski resorts over the winter season (also axed in 2020), and Disneyland Paris (axed in 2023). The financial challenges brought by Covid are partly to blame, although the central reasons for Eurostar’s reduced network are changes to EU border checks that will soon come into force, and complications caused by Brexit.

“St Pancras was not designed for a situation where you were going across a hard border,” explains The Man in Seat 61 rail blogger Mark Smith. “The passport checks and the threat of greater checks in the future [with ETIAS and EES – see below] have put the brakes on. Eurostar is concentrating on the core routes until they can get this under control.

“It’s also affecting how many seats Eurostar is selling,” Smith adds. “They’re restricting departures, and they are even not selling some seats on some trains because they don’t have the capacity to process all of the passengers. This means sold-out trains and higher fares.”

At one time, there was even hype around a possible night service. The Nightstar sleeper train would have enabled passengers to embark at Plymouth, Glasgow, London or Swansea and wake up in France or Belgium, and perhaps beyond. The rolling stock was ordered and some carriages were built, but in 1997 – against the backdrop of booming budget airlines and with the delays in the opening of HS1 – the project was canned and has never resurfaced.

So in response to that 1987 poster: yes, British passengers travelling to the Continent can indeed get from A to B, although if we want to travel beyond five European destinations, we do still have to worry about C. Thankfully, Europe’s efficient high-speed rail network and sleeper start-ups have made that final stage easier than ever.

Challenges and competition

So what lies ahead, as the Channel Tunnel turns 30? Both Eurostar and LeShuttle face significant border and security overhauls in the near future. The European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) – effectively a €7 (£6) visa-waiver scheme – will become a burden from 2025, as will the EU’s Entry/Exit Scheme (EES; from late 2024) which will require non-EU nationals to supply biometric information – a face scan or fingerprints – before entering or exiting an EU state.

Precise dates and details are thin on the ground, but Eurotunnel has previously estimated that the average time of processing a car at Folkestone will rise from less than a minute to up to seven minutes, and Ashford Borough Council in Kent has warned of possible 14-hour delays at Dover port. Eurostar and Eurotunnel are overhauling their departures terminals in preparation – the latter is spending €80 million (around £70 million) on expanding its terminals in Folkestone and Coquelles.

That aside, the greatest shake-up in the next decade will be the dawning of competition for Eurostar. The Spanish start-up Evolyn hopes to offer connections from the UK to “several countries” before the end of the decade, while Dutch rail firm Heuro and even Sir Richard Branson also have their eyes on the line.

Many feel that this can only be a good thing: “Thirty years is far, far too long to operate without competition,” says Nick Trend, The Telegraph’s chief culture and consumer editor.

A spokesperson for Getlink, the parent company of LeShuttle, said: “If choosing to travel by train rather than plane or by using ferries brings benefits to the planet, then expanding high-speed rail travel between London and new destinations in mainland Europe can only be a positive thing.”

For all the modern-day challenges, the Channel Tunnel remains a feat of engineering for the modern age. It is still the longest subsea rail tunnel in the world, and it has transformed how we think about travel to Europe. Nobody bats an eyelid at seeing Paris or Brussels on the departures board at St Pancras International, or driving on to the shuttle for a weekend in northern France. And others have taken inspiration: just this week, fresh plans emerged for a tunnel between Spain and Morocco, the Faroes built a tunnel between its islands, and even some of the Scottish isles are mulling the idea of subsea connections.

Have no doubt, the tangly EU border changes will bring fresh challenges, but as technologies advance and train stations adapt, these issues will not be terminal. If anything, the opposite is true. Those twin lines beneath the Channel will become more vital than ever before as the climate-aware population pivots away from flying, and a wider network at cheaper fares will help to usher in the new era. There is still light at the end of the Channel Tunnel.

Source Agencies