-

When Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, it caused enormous devastation.

-

The eruption triggered mudslides, an explosion, and plumes of ash that did enormous damage.

-

The death of 57 people led to large changes in how the US monitors and prepares for eruptions.

On May 18, 1980, Don Swanson placed a frenzied call to his wife to let her know that he was OK. “That’s nice,” she said, unconcerned. She had no idea her geologist husband had spent the morning in a plane flying by an erupting volcano.

At 8:32 a.m. Pacific Time that day, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake had shaken Mount St. Helens, leading to its eruption.

Its conical top collapsed into a horseshoe crater, sending rivers of mud and rock down its side and an enormous blast of heat and gas to the surrounding forest. Ash clouds wafted for over 930 miles, all the way to central Montana.

The devastating natural disaster killed 57 people and was the most destructive volcanic eruption in US history. It leveled trees, destroyed bridges, and caused more than $1 billion in damages.

Just a few years before the eruption, The New York Times described Mount St. Helens as a “relatively little known volcano 50 miles north of Portland, Oregon.” Its eruption forever changed the way volcanologists, geologists, and other scientists perform their jobs.

To commemorate the anniversary of Mount St. Helens’ eruption, here’s a series of photos that captured the immense devastation it caused 44 years ago.

Years earlier, scientists predicted Mount St. Helens would violently erupt.

In 1978, the USGS issued a report stating that Mount St. Helens had the potential to violently erupt before the end of the millennium.

The last known eruption had been in 1857. Over the past few centuries, its recent dormant periods lasted an average of 123 years. It was only a matter of time.

In March 1980, earthquakes caused cracks in the volcano, sparking alarm.

In the spring of 1980, Mount St. Helens had been trembling for weeks. Thousands of small earthquakes in March and April caused cracks in the summit. On March 27, steam started pouring out, turning the snow an ashy gray.

“That’s when it becomes this multi-agency response because now you have to prevent people from getting too close,” Liz Westby, a geologist with the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory, told Business Insider. “It could possibly erupt, but that wasn’t a for-sure thing.”

Meanwhile, people climbed on their roofs to take pictures of the steaming top. “Everyone really wanted to catch that glimpse of Mount St. Helens,” she said.

When the earthquake hit on May 18, its northern side collapsed. That triggered a debris avalanche, careening down enough rock, dirt, and snow to fill a million Olympic swimming pools. Some of it traveled as far as 14 miles away.

Ash-filled plumes rocketed 650 feet into the sky.

A super-hot mix of rock, gas, and ash caused incredible destruction.

The avalanche sheared off part of the cryptodome, a magma-filled bulge. It had swollen part of Mount St. Helens’ north side by about 450 feet.

Rapidly expanding gas then caused a devastatingly powerful blast that exploded sideways instead of up and formed what’s called a pyroclastic flow. The mixture can reach blistering temperatures of 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

“That is such a hot, thick, gas-rich flow that it essentially kills everything in its path,” Westby said. The heat, force, and high-speed debris can all be deadly. It knocked over trees, leaving them stripped and looking like toothpicks.

Moving at 300 miles per hour, the flow traveled faster than the debris avalanche, covering roughly 230 square miles — an area nearly the size of Chicago.

“Then you see this plume rising up,” Westby said. This one, full of ash and rock, rose as high as 80,000 feet. The eruption lasted nine hours.

Melting snow and ice mixed with rocks and ash turned into mudslides.

Mount St. Helen was still snowcapped in May when it erupted. The scorching heat turned ice and snow into gushing water that took rocks and soil with it.

Known as lahars, these 100-mile-per-hour volcanic mudslides ripped up trees, destroyed over 200 houses, and took out bridges.

Millions of tons of ash traveled hundreds of miles, closing highways and canceling flights.

Westby was at Eastern Washington University, not far from the Idaho border, when the volcano erupted. What looked like an ominous line of dark clouds drifted in the sky above. “I thought, wow, that’s the weirdest thunderstorm I’ve ever seen,” she said. It turned out to be ash.

Wind blew roughly 520 million tons of ash and volcanic glass to eastern Washington, Idaho, and Montana. It was dark enough to obscure the sun in some cities.

It settled on everything, leaving trees that looked like they’d been dusted with snow.

“This ash, it’s fine like baby powder,” Westby said. Driving through it would stir it back up into the air.

For days afterward, authorities closed highways and canceled flights because of the poor visibility and the ash’s potential to damage plane engines, Westby said.

The eruption killed 57 people, including USGS geologist David Johnston.

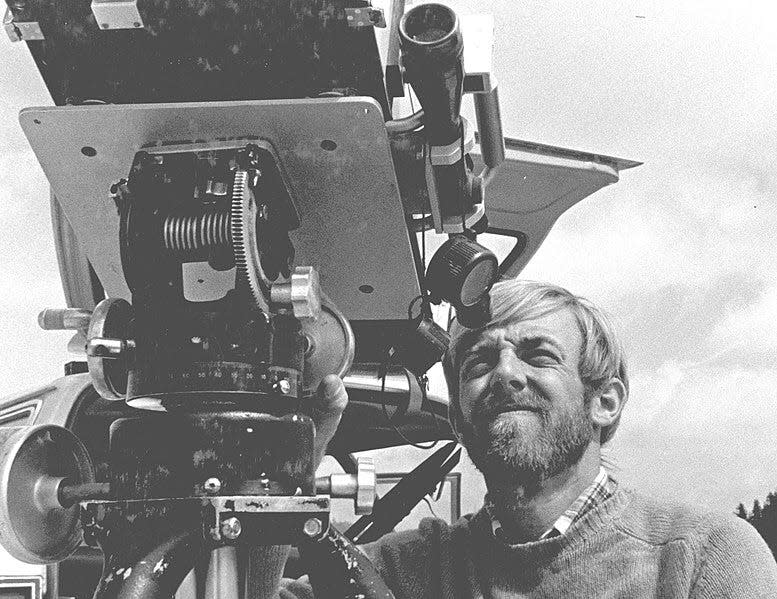

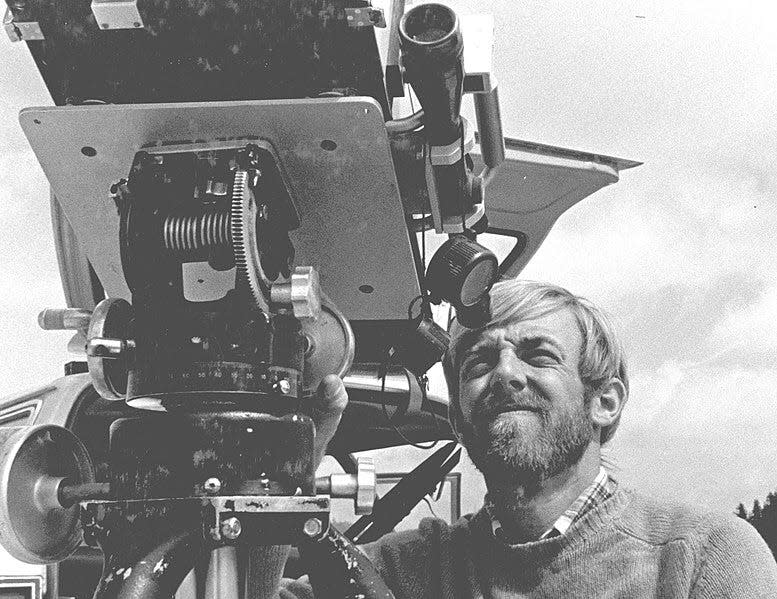

One of the first USGS geologists at the volcano was David Johnston. He had been closely monitoring Mount St. Helens during its many earthquakes.

On May 18, Johnston was only six miles from the volcano. As the eruption started, he radioed a final message to a nearby Washington city: “Vancouver, Vancouver. This is it.”

After that, Johnston’s death would have come within a minute, his fellow geologist Swanson wrote.

“It hit home to us as geologists, as volcanologists, how important it is to have monitoring up at the volcanoes and to install sensors before unrest so that we don’t have to have people up there in harm’s way,” Westby said of Johnston’s death.

Leading up to the eruption, experts created safety zones around the volcano. Only essential workers could go to the red zone.

However, the majority of the 57 people who lost their lives were outside the red zone, according to NPR. Many were killed by the lateral blast, Westby said. It ended up being more powerful than anticipated.

“It still gets me a little bit, thinking about that,” she said, “but that really influences how we feel about hazards today.” Now, she said, hazard maps are much more accurate and take into account a range of an eruption’s possible outcomes.

The eruption destroyed trees and killed wildlife, but many species survived.

Over a week after the eruption, researchers from the USDA Forest Service started looking at the ecological impact. Ecologists were shocked by what they saw at Johnston Ridge, about six miles from the summit.

They had expected to find nothing. Instead, there were still carpenter ants, frogs, pocket gophers, spiders, and other signs of life.

Thousands of large mammals like elk and bears didn’t survive, but other species of plants and animals were buried in snow or sleeping in their dens.

The blast zone where a hot flow of gas toppled trees is now known as the pumice plain, named for the porous rock that volcanoes create.

Initially, nothing survived in this area. It was two years before researchers saw the first plant, a prairie lupine. The purple-flowered perennial is known to be resilient.

It took four years following the eruption for new greenery to shoot up in the “ghost forests” where the volcano left broken and dying trees.

In the decades since, the ecosystem has drastically changed.

In the over 40 years since the eruption, a new ecosystem has slowly emerged. In the absence of larger predators, their prey thrived.

The smaller animals and dormant plants that survived the volcano’s destruction are still there, and bears, cougars, elk, and mountain goats have been spotted, too, The Seattle Times reported in 2020.

That doesn’t mean Mount St. Helens is back to normal, ecologist Charlie Crisafulli told the Seattle Times. With the pumice plain area starting from scratch, ecologically, what’s happening there now is unique.

The eruption spurred changes to how the US monitors and responds to earthquakes.

In addition to ecology, Mount St. Helens offers opportunities for other kinds of scientific research. Two years after the eruption, the USGS established the Cascades Volcano Observatory to better monitor the volcanic range.

The Observatory, which was dedicated to David Johnston, is one of only five in the US. It’s become a kind of laboratory for volcanic research and monitoring.

It’s also helping to train what could be the next generation of volcanologists. Every summer, Westby and the Mount St. Helens Institute run a camp for middle school girls called GeoGirls.

“We treat them as though they were our field assistants, to give them an idea of what it’s like to work on volcanoes,” Westby said.

Mount St. Helens could erupt again.

Mount St. Helens continued to have smaller eruptions through 1986 and then had more between 2004 and 2008. “They are active volcanoes,” Westby said of the Cascades, the volcanic arc that runs through several states and Canada. “They’ve erupted in the past, and we know they’ll erupt in the future.”

Of all the Cascade volcanoes, Mount St. Helens is the most active and most likely to erupt again, Westby said. But the technology to predict eruptions has vastly improved.

In 1980, Mount St. Helens only had a single seismometer, Westby said. “Now we’ve got 20,” she said. These newer devices are more sophisticated and can detect smaller earthquakes that could signal an impending eruption.

GPS data can also alert scientists if the ground is deforming. And software can help them process the data more quickly. In the 1980s, scientists were making the calculations by hand.

As the sensors help geologists keep an eye on what’s happening beneath the ground, Westby says people should feel free to enjoy the volcanoes. “They’re safe to be around right now,” she said, “but you never know what happens in the future.”

Read the original article on Business Insider

Source Agencies